Friday, 6:01am

30 November 2012

Free listening and learning

Do university blogs still have a role to play in developing links between students, institutions, countries and disciplines? Essay by Neil McGuire

The design course blog, over a decade after blogging hit the mainstream, is still relatively rare, writes Neil McGuire. But when used imaginatively, they have the potential to enhance the educational experience on a number of levels.

Course blog as critical and reflective tool

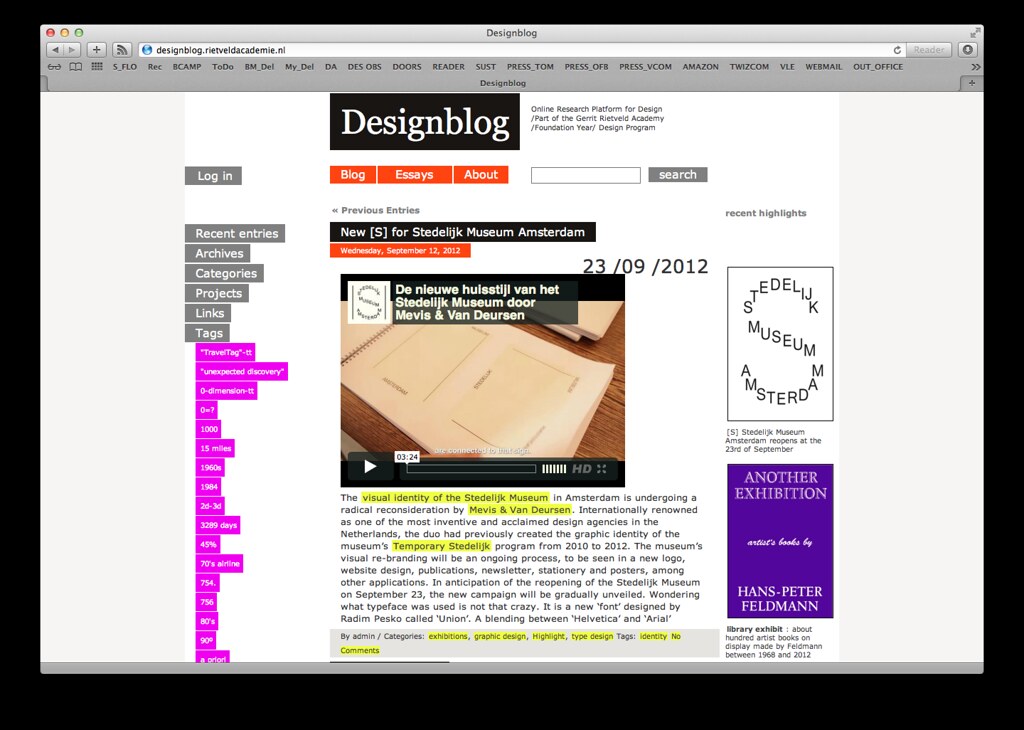

Blogs can be a discursive tool, for debating ideas but also offer the potential to connect these ideas with an expanded network of theory and practice available online. This networked approach is embodied in Designblog, the ‘research blog’ of the foundation design year at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie. It sets out its objectives as follows:

‘Designblog is not a regular blog. It is a complex and layered system in which facts are more than facts alone … It is a network of Metadata, an experimental blog for all Rietveld’s foundation year students. It is an instrument, and it is your platform for publishing.’

While Designblog is still very much embedded in studio practice, sites such as Limited Language also incorporate printed output (see Jane Cheng’s review in Eye 75), and take these debates to a wider audience. Colin Davies of the University of Wolverhampton, who co-founded Limited Language in 2005 with Monika Parrinder of the Royal College of Art, says the initial idea was to create a discursive platform for critical debate. ‘When we started nearly a decade ago the most exciting ingredient was the possibility of instant feedback. Of course today that feedback loop has become rather congested. However [blogs] still offer new potential for blended learning, and the opportunity for ‘students to see their thoughts and words appear in a public dialogue, rather than the usual to and fro between tutor and student in traditional essay writing’.

This is extended further by critical design courses such as D-Crit at SVA and the Critical Writing in Art and Design course at the RCA, which use their blogs as a central (public) space for the evolution and dissemination of student (and staff) projects.

D-Crit

Feedback Loop

While making process visible or tangible in this way might be seen as a universal good, it is always closely followed by concerns about whether blogging leads to an aggregation culture of surface-only investigation – a rapid recycling of ffffound images and styles.

Some of these concerns about Web literacy may appear over-exaggerated, but it is worth exploring in more detail the implications of, in the words of David Coyle, a ‘graphic-design-will-eat-itself’ culture.

Samuel Bonnet (of the Parallel School) adds: ‘It is so easy to copy a picture, using the same typeface and make a similar typographic composition, and we, young designers, look at so many things that we have a culture of quantity, developing an intelligence of watching and reproducing … maybe the good graphic design student today mustn’t have any website or blog, maybe (s)he just has to protect himself from the flow, and I know that some are…’

Course blog as project tool

Blogs can also function as rich, but sometimes short-lived, collaborative research environments on a project by project basis. In a project on the future of reading run by Lust with students at ESAD Valence, the project’s Tumblr site became alive with a tightly focused set of references within a very specific niche activity, enabling the quick sharing of reference material and development of ideas. It also provided a handy on-the-fly way of revisiting parts of the project and collective note-taking.

Peter Nencini, a lecturer at Camberwell College of Arts, believes there is a greater role for the ‘comment’ function to play in live annotation: ‘At the moment it feels too passive; or, in the social networking context, edging somewhere not nice.’ By way of comparison he references Matthew Stadler of Publication Studio, who ‘talks about the PDF strand of their published books and a live annotation process, which echoes the moment when he would take books out of the library and find other researchers’ notes in the margins. This seems like an enrichment mode’ – a mode that courses could develop when thinking about layered learning.

This, of course, raises interesting questions about the traditional reading list and a staff-centric view of knowledge transfer that can still sometimes prevail. Alternative modes of reading, writing, collating and publishing continue to disrupt (in a good way) and force us to re-examine existing academic value systems.

Course blogs as extended family

Course blogs, by their inherently interconnected nature, offer further opportunities to extend the collegiate community of any given institution beyond its campus. This can be through alumni who continue to blog with the department, and industry professionals who both contribute to and read these blogs. Vocationally focused blogs such as Fuel at the RCA offer an open way of sharing information about future careers and advice, and in a way that potentially makes the most of the ‘wisdom of crowds’.

Blogs also provide a channel for institutions to connect with other courses, students and staff. Limited Language suggests that a possible future for design course blogs ‘may be in developing links between institutions, countries and disciplines. The trip is a simple and effective tool for communication across geographies … [an] underutilised aspect is how we can use [technology] in this more globalised educational framework.’

Non-format

Blogs as incidental promotion

Perhaps unintentionally, and maybe all the better for this, course blogs have become a very good way of promoting design programmes. Nencini sees the blog ‘as offering an authentic view of the kinds of activity and discourse that happen in the studios of the course. It is free of institutional edit, at a stage where prospectuses and open days have, to an extent, become a quick, open pitch to prospective students and their families.’

Other courses have further blurred the boundaries, with their websites adopting Web 2.0 characteristics, and a spirit of ‘open’ communication. Yale University School of Art’s website is built on a wiki, in theory allowing any student or member of faculty to contribute to and edit pages. The System Design course at Academy of Visual Arts Leipzig utilise webpages somewhere between a work-bench and work-in-progress blog.

But is this openness always welcomed by the host institution? Nencini notes that, in a culture where the default is set to share, ‘there is also the question, on everybody’s part, of “keeping our powder dry” – the worry that freely accessible content online might encourage a kind of remote learning culture’. Ultimately however, he feels ‘it’s an act of confidence, generosity to the wider culture and also somehow credit[s] the students on that course with the intelligence to know what it means to be in the studio, among other people, making and thinking. The “live” element sublimates any pre-posted planned content so I think longer term it’s always about how the Web can intensify the studio moment.’

Department 21

Online and Off

What often emerges from this discussion is a false dichotomy, between online and offline culture. In reality, we’re dealing with a parallel situation where (as Nencini notes) ‘Having process visible – either teaching or making – allows for a more textured conversation. A side-by-side mentality.’

Therefore an interesting facet of these online spaces is what other types of activity might emerge around them. The Parallel School, a student-organised adjunct to business as usual at the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, points the way towards some of these possibilities. While not necessarily intended as a wholesale replacement for institution-based studio education, it nevertheless created an additional layer of fluid, student-directed learning, that through its online existence made contact and collaborations with Manystuff, the RCA (and Department 21) and a likeminded group of other protagonists along the way. More importantly, through its concurrent online documentation and discussion, it presented the possibility to work in this way to a vast number of other students elsewhere.

Writing about Paul Elliman’s Wild School in Eye 25, Rick Poynor lists among its distinctive aspirations that ‘everyone will be an auditeur libre as the French put it, a “free listener” able to wander at will and determine his or her educational needs’.

‘At that time,’ Poynor notes, ‘the project was more a proposal than fully functioning public reality’ … The challenge being to ‘transform this proto-school from a list of sometimes eccentric links … and recycled teaching briefs … into a richly imagined and responsive experience in self education.’

This was in 1997. The digital tools to assist in this happening are now freely available, and their increasing uptake by existing design courses and autonomous student groups alike open up some exciting possible futures for design education both on and offline.

Neil McGuire is a designer and tutor. He blogs at OffBrand and on Visual Communication, the Communication Design course blog he established at Glasgow School of Art with Lizzie Malcolm, Sam Baldwin and Brian Cairns.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 84 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.