Wednesday, 7:30am

13 April 2011

Out of space

Charting the pervasive visual language of science fiction

A forthcoming exhibition about science fiction at the British Library will be full of amazing images as well as stories.

We spoke to Katya Rogatchevskaia, co-curator of the British Library’s exhibition, opening on 20 May 2011 and titled: ‘Out of This World: Science Fiction but not as you know it.’

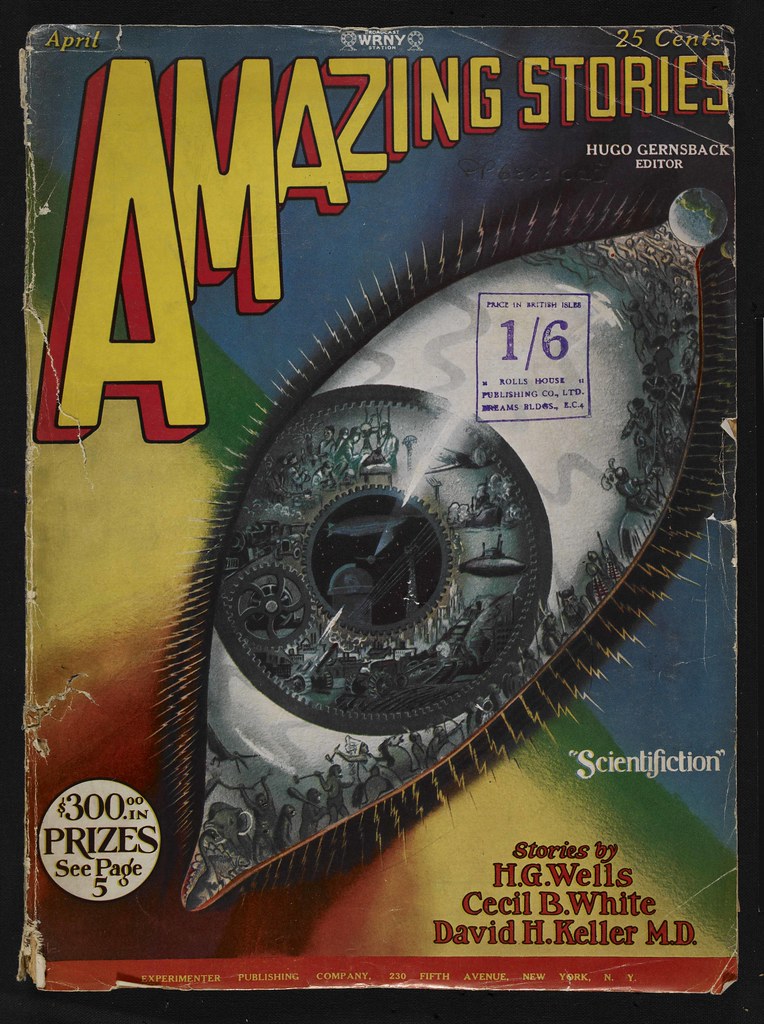

Top: Frank R Paul, April 1928 ‘Eye’ cover for Amazing Stories, the world’s first science fiction magazine.

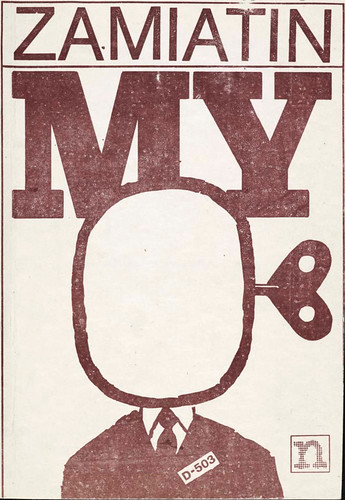

Below: Polish samizdat edition of Evgeny Zamyatin’s My (We), published in Warsaw, 1985.

EYE The exhibition looks at what distinguishes science fiction from related genres like fantasy and horror. Is there anything distinct about the visual language?

KR Science fiction is about imagination, speculations and vision. It’s a genre that both invites and defies accurate interpretation through illustration. The exhibition will explore the full spectrum of visualised science fiction, from science fiction that is theoretically possible and based on ‘real science’, designed to instruct as well as entertain – such as the works of H. G. Wells and Jules Verne – to the more imaginative and speculative science fiction of virtual worlds, where dreams can play as big a role as digital realities.

The visual language of science fiction is something that we readily understand and return to constantly. If you asked a selection of people to draw an extraterrestrial life form, it is highly likely that you would be presented with at least a few domed-headed, boggle-eyed beings. This representation of aliens is not based on any real science, but it has entered our visual culture and become iconic.

The same motifs appear again and again in science fiction, often straying into mainstream fiction. Obviously there is some cross-over with fantasy and horror, and looking at science fiction in a vacuum would not be helpful, but we aim to show that science fiction has been incredibly inspirational in its own right – to popular culture, literature and art.

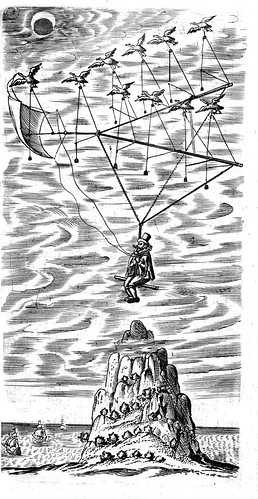

Below: Francis Godwin’s Domingo Gonsales trained a flock of ganzas to transport him in The Man in the Moone. From the first edition, 1638.

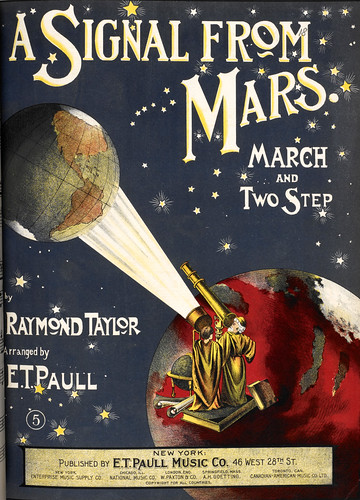

Above: Raymond Taylor’s composition, A Signal from Mars, 1901.

EYE Can you comment upon the relationship between science fiction literature and illustration?

KR From the end of the nineteenth century, popular fiction became more and more linked to illustration, and illustrators and graphic artists started exploiting science fiction as a source of inspiration. Science fiction from this period plays an important role in the history of book cover design, with the automation of book production making illustrated covers a marketing tool – and we have some fantastic early examples of this phenomenon in the exhibition. We also have a number of artists’ books, which are some of my favourite items – for example, William Morris, Barlowe’s, guide to extraterrestrials, Barry Moser’s visualisation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1983), and especially – Lem Mróz.

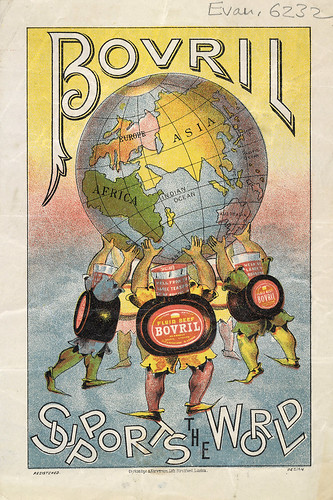

Below: Bovril advertisement, ca.1890.

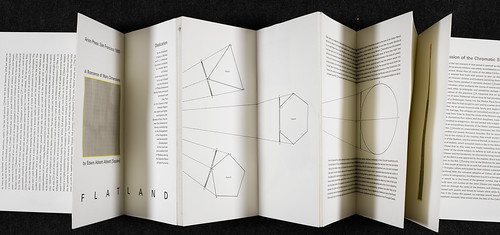

Visitors will be able to see a 30ft long concertina book version of Edwin Abbott’s Flatland, published in 1980 by the Arion Press (above). Flatland is a satire on Victorian society, representing the class system through the metaphor of geometry, and this edition goes one step further, reimagining the book itself as a geometrical form. We are also showing the artist Luigi Serafini’s Codex Seraphinianus (1981), an encyclopedia of an imaginary world, written in an imaginary language; as well as Paul Scheerbart’s portfolio of illustrations, Gallery of the Beyond from 1907, which is a visualisation of aliens from ‘beyond the Orbit of Neptune’.

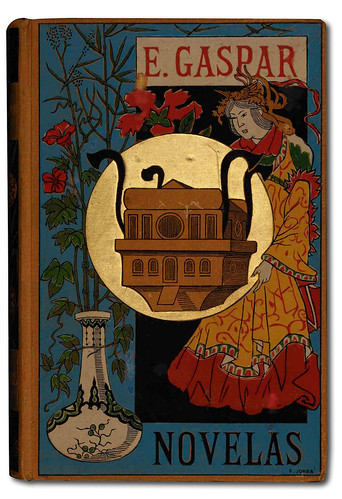

Above: Cover of Gaspar’s Novelas (1887) for ‘El Anacronópete’ depicting the earliest known portrayal of a time machine.

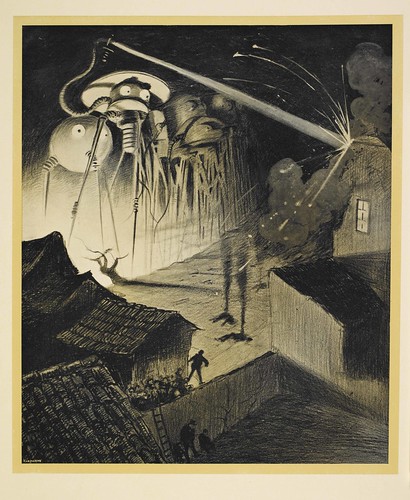

Below: The Martians from H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds; as depicted by Alvim-Correa in the Belgian edition, La Guerre des mondes (Brussels, 1906).

The exhibition will also show various other approaches to illustrating. H. G. Wells’ famous The War of the Worlds is shown in three editions. Tripod aliens are exhibited side by side as visualised by three prominent book illustrators: Warwick Goble, Jacobus Speenhoff and Alvim Corrêa – in this way we can see how the same work was interpreted entirely differently, whilst still having a powerful impact.

EYE In what ways will visitors be able to engage with the visual language of science fiction during this exhibition?

KR Visitors will be able to see the whole spectrum of the visual language of science fiction. They will have a chance to compare different techniques, styles and forms of illustrations and enjoy the visual side of imaginary worlds. They can see original artwork by contemporary artists (David Hardy, Bryan Talbot, Les Edwards, James Richardson-Brown). They will be able to take part in our interactive exhibits, by designing their own alien to be part of the exhibition, and sending a postcard from a science fiction landscape. I hope also that the exhibition will inspire artists and designers to create new work, and perhaps make people think again about the ways in which science fiction speaks to our imaginations.

20 May > 25 Sep 2011

Out of this World: Science Fiction but not as you know it

PACCAR Gallery

British Library

96 Euston Road

London NW1 2DB UK

www.bl.uk

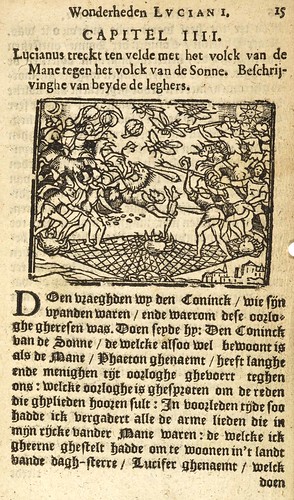

Below: Lucian of Samosata, True History, Dutch edition, 1647.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It’s available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. For an extensive (if so far incomplete), text-only archive of articles (going back to Eye no. 1 in 1990) visit eyemagazine.com. For a visual sample of the latest issue, see Eye before you buy on Issuu.