Thursday, 10:28am

22 January 2009

Treasure trove of graphic resistance

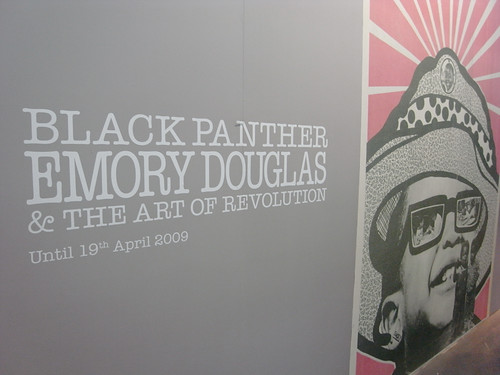

Black Panther: Emory Douglas and the Art of Revolution

What better time to see an exhibition of work by Emory Douglas, the official artist of the Black Panther Party, asks Noel Douglas (no relation – Ed). Like the Panthers, Barack Obama’s campaign also made highly visible use of ‘street’ graphics, with strong networks of grassroots flyposting, and the connections – and differences – between the two periods are made obvious as you walk around Black Panther: Emory Douglas and the Art of Revolution at Urbis in Manchester.

First, there is no doubt about the positive distance travelled in America since the late 1960s. The first part of this superb retrospective deals with the history of racism in the US – slavery, the birth of the Civil Rights movement, through the assassinations of Martin Luther King, John F. Kennedy and Malcolm X, and the radicalisation of the 60s that gave birth to the militant Black Panther Party, of which Douglas (at just twenty years old) was designer in chief and ‘minister of culture’.

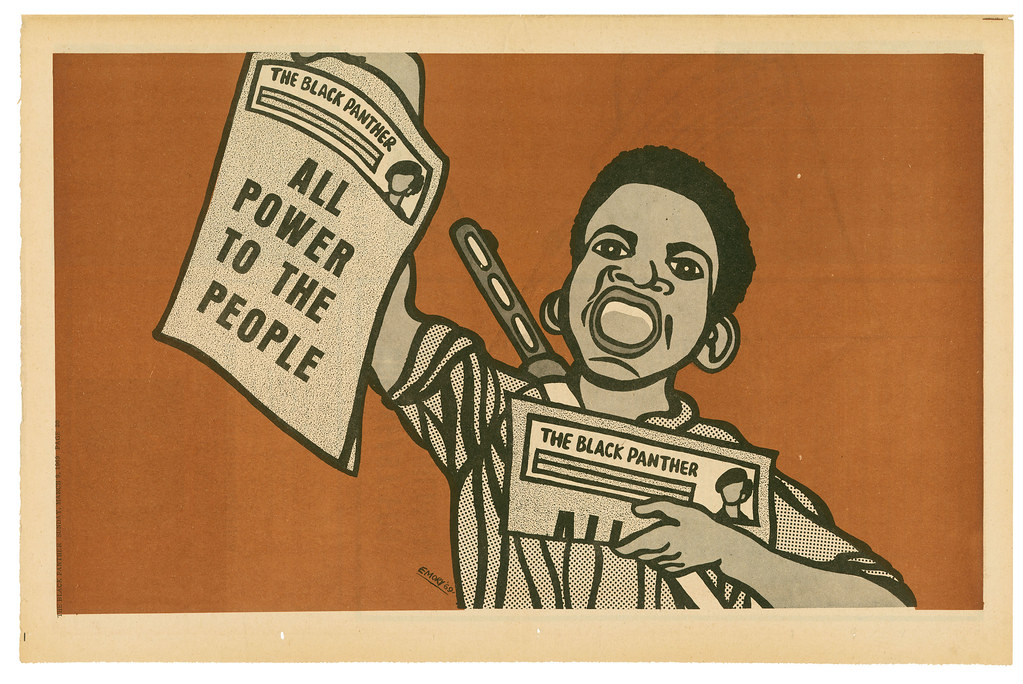

Above: a Black Panther Party activist sells Douglas’s designs on the street in Washington DC.

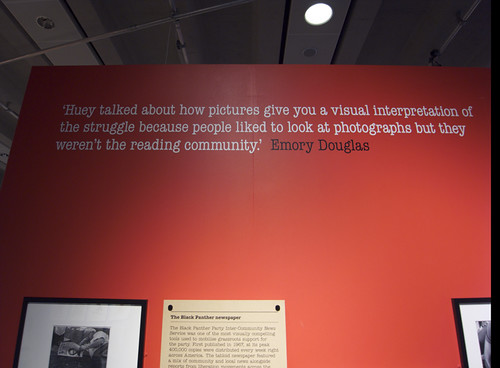

The gap between then and now lies in the way the politics informs the aesthetics. Though Shepard Fairey’s striking posters for Barack Obama resemble Douglas’s graphics, the slogans on them are vague – ‘HOPE’ (For whom? For what?), ‘PROGRESS’ (For whom? To where?) – and put a radical ‘street art’ gloss on the Democrats’ big business politics. Douglas’s work is strident, bold, biting, funny and passionate, and has an urgency that the Obama posters lack. Crucially, Douglas’s work was produced to serve as a weapon in the struggle of poor and working-class Blacks across the US, showing a people rising up, proud of themselves, and as likely to represent the ordinary folk in the ghetto as the leaders of the Panthers. Douglas applied the techniques he learnt in designing adverts to getting the message of the revolution out. As a wall in the exhibition boldly proclaims, echoing Rodchenko, ‘the community was the museum for the work’.

Unlike their popular image, the Panthers were not just about standing in leather jackets with guns outside police stations, they also developed scores of social programmes, such as free breakfasts for young children, and help for the elderly. Some of the most fascinating images in the Urbis show are posters promoting such programmes – what strikes you is the inclusivity and respect of the imagery toward the community. Old people, the young, women are portrayed in sympathetic and un-demeaning ways, often shown in poverty but never as unfortunate victims unable to change their situation.

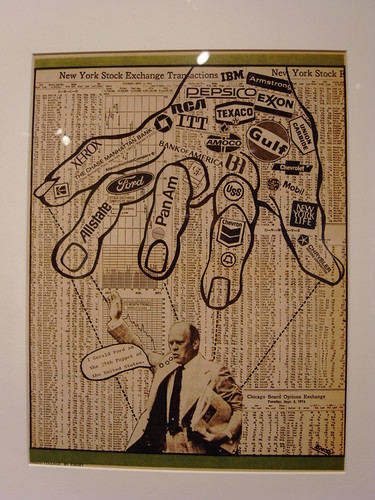

This is not to take away Douglas’s ability to create superb agit-prop for the party: the work is an incredible range of styles and processes, from drawn illustration to photomontage. Sharp thinking works against the constraints of finances – bold outlines, for instance, serve both to create striking designs and to overcome the technical limitations of misregistered trapping – elsewhere, subtle psychedelic influences are mixed with more traditional revolutionary iconography.

Above: illustration from The Black Panther newspaper, 21 September 1974, showing the president, Gerald Ford, controlled by corporate interests.

This thoughtfully designed exhibition is a treasure trove of graphic resistance, and Douglas deserves a much more visible standing as an innovator in graphic communication. As with John Heartfield 30 years before him, Emory Douglas put his talents to the service of the progress of humanity.

His example is an inspiration to all of us who think that graphic communication must meet human and not commercial needs.

Black Panther: Emory Douglas and the Art of Revolution

Urbis, Manchester, until 19 April 2009.

See also ‘Whose space’, Noel Douglas’s article about graphic resistance for Eye no. 66 vol. 17.

Above: montage from The Black Panther, 16 November 1972, showing Richard Nixon with his vice-president, Spiro Agnew.

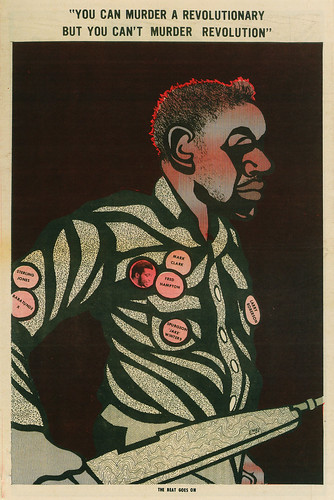

Above: poster, 5 December 1970. The quote is from Fred Hampton, leader of the Chicago chapter of the Panthers, who was shot dead during a police raid in 1969.

Below: The ‘education’ section of the exhibition, with in the foreground a Douglas illustration from 1973 showing citizens becoming informed about political issues.

Below: reworked image from the paper produced as a poster, displaying period psychedelic influences.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.