Friday, 1:09pm

29 July 2011

Visual sonata

The Quay Brothers create an intimate spectacle for Bartók and beyond.

Film-makers might spend a lot of time and effort trying to make a set look as dilapidated as Wilton’s Music Hall, the once-disreputable Victorian (built in 1858) venue in Wapping, writes John L. Walters.

In places, it looks like something the Quay Brothers might fabricate for one of their dark Surrealistic fables, except that they would never have the budget. So Wilton’s was an entirely appropriate venue for the Brothers’ collaboration this week with Russian-born violinist Alina Ibragimova.

The work of the Quay Brothers (aka the Brothers Quay) occupies a special place in contemporary visual culture. Using animation, puppetry, type, light, lettering and a dustily arcane approach to imagery, they have created a series of short films that are like little else. You can find much of their best work on a double DVD published by the BFI, and they were included in ‘Uncanny’, Rick Poynor’s 2010 exhibition of graphic design and surrealism at the Moravian Gallery in Brno.

Music is an important element in the Quays’ oeuvre: they have collaborated with composers Leszek Jankowski and the late Karlheinz Stockhausen, as well as designing opera and dance productions. They told me: ‘Music virtually prefigures every piece we’ve ever made, and it always presents itself as the most unattainable scenario that otherwise could not seemingly have been written.’

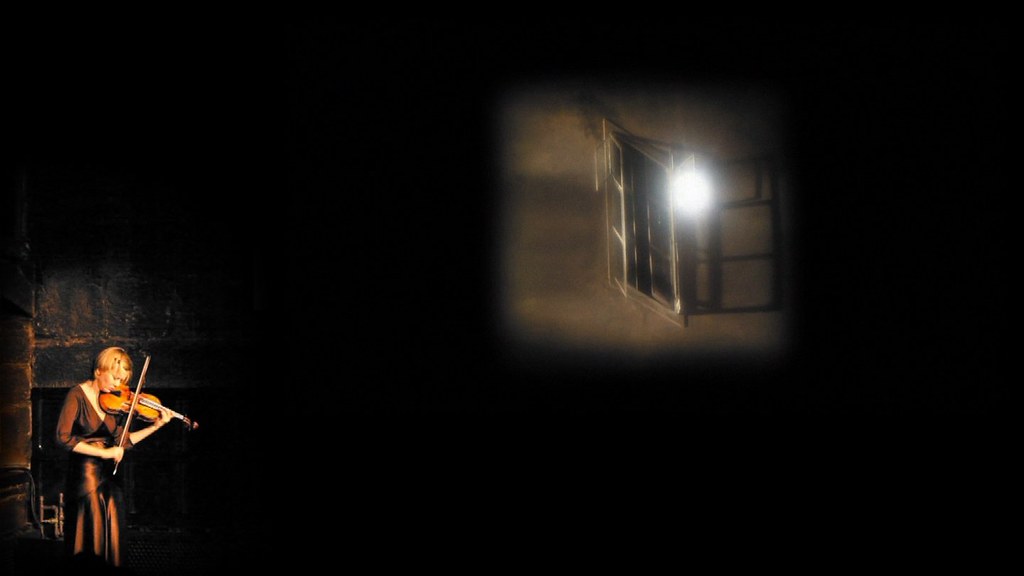

Above: photographs of Wilton’s by James Perry.

At the Wilton’s event, the repertoire comprised four solo violin works. The first two, Berio’s Sequenza VIII (1976) and Bach’s Chaconne (from the Partita in D Minor) were presented in dim illumination: for the Bach, a low-angled spotlight cast an eerie, Expressionistic shadow (like a more benign Murnau’s Nosferatu) of Ibragimova on the theatre’s ‘Peeping Tom’ safety curtain.

The Biber played through speakers during the interval while we wandered round the extraordinary spaces (above and below): many of the surfaces seemed to be crumbling before our eyes.

Through a gap in the wall of the upstairs ping-pong room we could glimpse bric-à-brac and scrap-screens that looked as through (Michel Faber’s fictional) Mrs Castaway had just abandoned them.

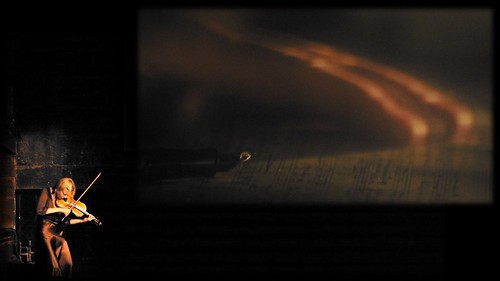

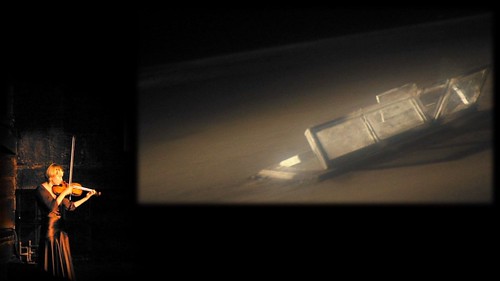

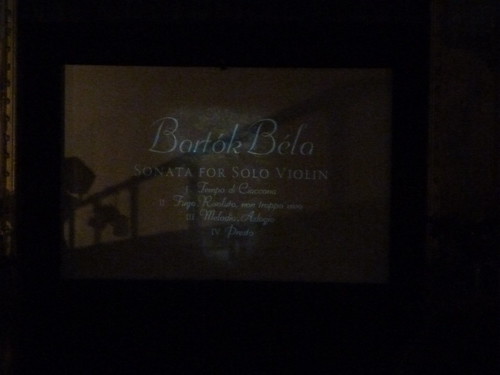

The main (and final) event was Bartók’s Sonata for Violin (1944), originally commissioned by Yehudi Menuhin. The performance was accompanied by a new film by the Quays entitled I looked back when I reached halfway, a slow, mysterious sequence of shapes and images: windows, shattered glass, a pencil, a pen and fingers scratching at a score, the contours of a face (perhaps Bartók’s) in close-up and the vision of a child’s face, surrounded by flowers, in a coffin.

The film is in four movements, like the sonata. Ibragimova used the start of each section as a visual cue to begin playing.

I asked the Quays (Stephen and Timothy, who tend to speak as one) about the project, which was a joint commission from the MIF (Manchester International Festival, where the same concert was performed at Chetham’s Music School), Create and the Barbican, who presented the Wilton’s event as part of Blaze.

JLW How did the project begin?

QQs Alina had been a big success at the Manchester Festival two years ago and [festival director] Alex Poots wanted to bring her back. He must have had the Bartók in mind and a film as well, which would have concluded the evening, but it was definitely based around Bach, since the Berio and Bartók were both derivative of the Bach solo violin works.

We based the film around images of the illness that Bartók would soon be finally diagnosed with [leukaemia] and the memory of a dead child from his childhood who refused to stay motionless in his mind. Once the pieces were chosen we went off to make the Bartók film. Alina plays directly to the images on the screen and at times almost uncannily seems to control the flow and speed of the images. We did a huge amount of research and have always been very partial to his music.

JLW Will the piece have a life after the final performance [at Wilton’s on 27 July 2011]?

QQs The film is entirely new, but it may have a further life as we’ve filmed her playing the piece at Chetham’s against the images with two cameras.

JLW Are there parallels between the Manchester event and Wilton’s, or have you had to rethink it?

QQs Alas, no parallels other than it being an equally beautiful venue. They are hugely different but Wilton’s is utterly unique and the QEH or the Barbican would have been totally antagonistic to the premise of this piece (the entire programme of Berio, Bach, Biber and the Bartók).

JLW There is a view of multimedia that sound and vision have to either a) conform, b) complement or c) contest each other … where do you see your work with Alina fitting into this?

QQs Hopefully they complement her [music] as a parallel realm. Above all this piece of Bartók is not film music in the way that say his Concerto for Orchestra could be … it’s a concert piece and therefore it obeys a more strict logic than, say, working with Stockhausen, where his score was one vast cosmic painting ensconced in the words of music.

JLW Do you enjoy being involved in a ‘real-time’ event, as a change from making films and, if so, are you likely to do more?

QQs We’ve worked in opera several times but that’s quite grand by comparison to the intimacy and intensity of a venue like Chetham’s or Wilton’s. It’s a challenge for which the space itself is the ultimate destination, rather than, say, the cinema as we otherwise know it. Here there is Alina as live narrator and interventionist – violently subduing the images.

Portrait of Alina Ibragimova by Sussie Ahlburg.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It’s available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop. For a taste of the new issue, see Eye before you buy on Issuu. Eye 80, Summer 2011, is out now.