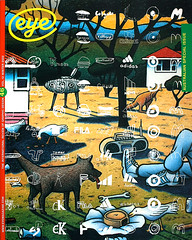

Winter 2002

Look inward: graphic design in Australia

Garry Emery

Nova

Fabio Ongarato

Stephen Banham

Les Mason

Feeder

3 Deep Design

Studio Anybody

Barrie Tucker

De Luxe

Ken Cato

Mimmo Cozzolino

Precinct

Is Australia’s global cultural impact reflected in its graphic design?

Seen from afar, Australia has always been an unknown territory when it comes to graphic design. Few Australian names are well known outside the country. Older designers may be familiar with figures such as Ken Cato, Garry Emery and Barrie Tucker, but no younger graphic designers have had the kind of international impact that Marc Newson made on furniture or Baz Luhrmann made on art direction for film. In the last decade, few Australian designers have promoted themselves beyond the country’s shores. Stephen Banham, as a self-publisher, is a striking exception. Mambo, with one of the most original graphic identities of any clothing company anywhere, has received little attention in the design press. Designers invited to lecture in Australia often seemed to return with the view that little was happening down under.

This special issue of Eye has its origins in a disbelief that such a remarkable and fascinating country could be so quiet in a graphic sense and in a hunch that there was more going on than met the eye. In recent years, Australia has emerged as a vibrant contributor to international culture at all levels, with an impact relative to its small population (nineteen million) that other countries might envy. Australian actors and musicians seem to be everywhere. Australian architecture is stunningly inventive; one of the country’s finest architects, Glenn Murcutt, won the prestigious Pritzker Prize in 2002. Australian writers such as Tim Winton and Peter Carey, winner of the Booker Prize in 2001, are held in high regard. Australian film-makers continue to produce some exceptional films, most recently Rabbit-Proof Fence. As Australians never hesitate to tell you, their cuisine is world class, and standards of hospitality are very high. Australia today is an exciting, energetic, hugely stimulating place to visit. Its globally acclaimed staging of the Olympics in 2000 did much to boost national self-belief.

Graphic design is not untouched by this sense of energy and conviction and in the past few years there have been some interesting changes. To understand Australian design’s position now, though, it is necessary to consider how it has developed. Australian practitioners have always measured themselves against what was happening abroad and from the 1930s to the 1960s – and beyond – many would seek work experience overseas. The American designer Les Mason, a former sailor and bar owner, who arrived in Melbourne in 1961, was a key figure. ‘He was the most informed person that I’d come across,’ recalls Garry Emery, ‘and he was the one that really built bridges for me, made design legible so that I could grasp the social connections.’

Mason was steeped in ideas about type and spatial organisation brought to the US by the European émigrés. He had read György Kepes’s The Language of Vision (1944); the book was a decisive early influence on Emery, too. The young Australian’s other sources included Danish and Scandinavian Modernism – seen in furniture and homewares – European Modernists such as Max Bill and Josef Müller-Brockmann, and Karl Gerstner’s Designing Programmes (1963). Then came Push Pin and Herb Lubalin. As Emery describes it, Australia in the 1960s and 70s was not an easy place to be a designer: it was a self-conscious, laconic, masculine society, shaped by its convict origins and deeply suspicious of anything perceived as intellectual or highbrow. ‘I believe that’s very much part of the Australian psyche,’ he says. ‘It’s a kind of distrust. Maybe it’s not so visible now, but it’s not so long ago that it was highly visible.’ Design was a ‘cissy’s game’ that Emery would only ever discuss with fellow designers and he thinks this anti-intellectualism persists even today. The Australian belief in an egalitarian society goes back to its earliest days and ‘tall poppies’, people who try to stand out above the crowd, have to be lopped to restore equality. This distaste for the ‘self-promotion caper’, as a Sydney-based designer described it to me, is perhaps one reason why Australian designers have tended to be overlooked.

Another result of Australian design’s tendency to underplay itself is that there are surprisingly few sources of information about it. Geoffrey Caban’s A Fine Line: A History of Australian Commercial Art, published in 1983, is the only detailed general study, but has been long out of print; nothing comparable has since appeared. Even more crucially, Australian graphic design has lacked a vigorous, well established design press to report on its activities, analyse developments, encourage debate and reflect its sense of identity, though there are signs that this could change. In June 2001, Desktop magazine abandoned its focus on technology to concentrate on new developments in design; a size change and a lively redesign reflected its new direction. Nigel Beechy, president of the New South Wales branch of the Australian Graphic Design Association (AGDA), believes there is a pressing need to improve the quantity and quality of design discussion. ‘A lot of design writing – and there isn’t a lot – tends to have almost a pop star mentality, going for the cool, groovy designers of the moment.’

Design as a special case

AGDA, founded in 1988 and staffed by enthusiastic volunteers, has undoubtedly made a significant contribution to the development of Australian design. It has a voluminous website, organises lectures and holds National Awards every two years (the 2002 awards have just been announced). But it still has its critics. James de Vries of De Luxe, a Sydney studio specialising in editorial design work, doesn’t view AGDA as sufficiently representative. ‘It’s been a bit of a coterie of like-minded people who entertain each other,’ he says, ‘a very small segment of the industry.’ Graeme Smith, co-founder of Precinct, a medium-sized Sydney studio, suggests that AGDA’s focus on issues is too narrow. ‘For instance, they are forever talking about free pitching and the craft of graphic design and how clients need to be educated, but I think that’s just facile,’ he says. ‘It’s not the client that needs to be educated. It’s the whole culture.’

Smith argues that design in Australia is still a special case – luxury items for the affluent, rather than well designed things for everyone, which are part of the fabric of everyday life. Some areas of Australian life certainly do seem to be less ‘designed’ than others. Restaurants are often fabulous and wine labels are a minor art form, but supermarket design and food packaging, and retail design in general, are much less sophisticated. ‘In Britain, I’d say that generally the public is very well educated as to what design is,’ says Dean Hastie, a British designer who arrived in Australia in 1990 and co-founded the design company Nova in Sydney. ‘You walk into a supermarket and everything is designed to within an inch of its life and it’s the norm. But here it’s not.’ Others see it differently. ‘[Australians] have a much greater awareness of what good design is now, spreading through the echelons of the community, even down to your mums and dads at home,’ says Penny Bowring, managing director of Emery Vincent Design. ‘They are being fed better design and accepting it, which we always said they would.’

Any design-aware visitor to Australia will inevitably ask whether there are, or have been, characteristic and immediately recognisable national forms of graphic design. In A Fine Line, the Australian designer Arthur Leydin, talking about the 1950s, argues that Australian design should be assessed from a regional point of view and not in comparison with what was being done in Europe or the US. ‘Australian designers,’ he observes, ‘could only answer the cultural demands of the society of which they were a part.’ There have been periodic attempts to isolate and celebrate aspects of a specifically Australian graphic tradition. In 1980, Melbourne-based designer Mimmo Cozzolino, co-founder of the All Australian Graffiti design team, published Symbols of Australia, a dense compendium of early Australian trademarks that designers still refer to fondly. While similar material, in the US, continues to inspire a whole school of commercially viable and publicly admired pseudo-vernacular design, exponents of Australian vernacular such as Stephen Banham are the exception today. ‘Some people, if you ask that question [about Australian design], will trot out a whole lot of old photographs of stuff that looks like signage out of Californian Westerns – an English, colonial, Victorian thing,’ says Graeme Smith. ‘But I don’t know whether I can see it now.’

Australian designers would sooner smash their G4s than resort to clichés such as kangaroos, koalas and bush hats hung with bottle corks. Perhaps unfairly, the output of adman turned artist and entrepreneur Ken Done is often invoked as an example of a bogus form of Australiana. Done, who was the subject of an admiring retrospective at Sydney’s Powerhouse Museum in 1994, has a gallery and a shop in the city’s harbour where he sells wall paintings and merchandise bedecked with his sun-drenched, good-life graphics. ‘It’s second-hand Matisse rejigged with motifs of Australia, but it’s not Australian,’ insists Emery. Nigel Beechy suggests that it is Emery himself who has come closest to creating an Australian form of design. ‘I believe he was one of the few to create a unique vernacular, a unique form of expression,’ he says. ‘Some would say it is relatively Dutch, but that’s a superficial understanding of what he was trying to do. He was a severe Modernist. He loves his Surrealism.’

The uninhabited interior

Australia, as a landmass, is like nowhere on Earth and nobody who has been to the outback can fail to be deeply impressed – and perhaps even changed by the experience. As literary critic David J. Tacey shows in his book Edge of the Sacred, Australian literature has engaged obsessively and often fearfully with the country’s vast, psychically threatening, unforgivingly harsh and largely uninhabited interior. Only by experiencing a psychic connection with the landscape, suggests Tacey, will Australians learn to respect the ‘mythic bond’ between the land and its indigenous inhabitants.

So it’s odd, looking at contemporary Australian graphic design, how little it seems to be informed by a strong sense of place. In my own conversations with many Australian designers, few of them ever mentioned either the landscape or the Aboriginal people, who are so conspicuous by their absence from both the business and practice of design. ‘I don’t think we should necessarily go looking to be regional,’ says Emery, an admirer of Tacey’s work. ‘But if we look inward, then we can discover what is true to the place and create a sense of place and a sense of meaning that is Australian. The visual manifestation of that will be unique.’ For city-dwelling designers huddled on the continent’s coastal perimeter, to embrace the land would be to ‘look inward’ in both senses.

Now more than ever, though, Australian design is swayed by the pressure of external forces. Giant branding consultancies see Australia as a small but attractive market with plenty of growth potential. These ‘global players’, with offices everywhere, bring with them a corporate vision that treats design as little more than a matter of local ‘maintenance’ of international brands. In 1988, Interbrand opened a Melbourne office. More recently, Landor affiliated with Sydney agency LKS; FHA Image Design, creators of the 2000 Olympics logo, sold 70 per cent of its business to FutureBrand; Enterprise ID acquired Horniak & Canny; Attik opened a Sydney office; and Garry Emery sold Emery Vincent Design’s Melbourne office to Clemenger so he could start all over again. ‘For me, design has got so confused with business that it’s no longer design any more,’ he says. ‘It’s basically marketing … I think it’s the most boring thing in the world.’

Those on the consultancy side inevitably try to cast these developments in a positive light. They say it will lead to better training for designers, greater expectations of customer service among clients and higher standards of professionalism all round. According to one consultant, Andrew Lam-Po-Tang, writing on the AGDA website, another effect might be even faster adoption in Australia of overseas design trends (not that the process seems slow). ‘Once the new ideas land in [an] Australian subsidiary via the internal network, personal networks will take care of disseminating the ideas into the rest of the design community.’ What this would presumably mean in practice is more homogeneity, less regional difference and less chance of a specifically Australian approach to design finding national expression.

Simplify. Don’t look back

Perhaps it is no more than a coincidence, but the period during which most of the globals have arrived has seen the proliferation of an increasingly purified, uniform, neo-Modernist design aesthetic. The change can be clearly seen in the output of a company such as Nova. A few years ago, their work was compositionally intricate, with overlapping letters, type size changes, mixtures of serif and sans serif, and irregular picture shapes. Today, Nova use a severely simplified, impeccably tasteful sans serif palette familiar from the work of London designers such as Mark Farrow, North and Cartlidge Levene – all mentioned by Hastie. ‘For us,’ he says, ‘it’s a lifestyle thing, because we lead hectic lives and we thought: life doesn’t have to be this hard, let’s just simplify everything. So that’s what we did and we’ve never looked back since then. Why come up with a hundred different looks in a portfolio? It almost dilutes your personality, anyway.’

Many of the most highly regarded practices – the ones people consistently recommend, when asked – employ this stripped-down style: Precinct, with offices in Sydney and Melbourne; Feeder in Sydney; 3 Deep Design and Fabio Ongarato Design in Melbourne. It’s a forgone conclusion that almost any Australian cultural magazine – about film, fashion, architecture or design itself – will adhere to this inflexible dress code. Fabio Ongarato is perhaps the most exquisite and North-like of all in his pursuit of dynamically refined, Helvetica-based layouts that put maximum emphasis on sumptuously art directed photography, often for clients in the fashion industry. Ongarato’s studio is a design temple in the Vignelli mould, with half of the softly illuminated space given over to an entrance / meeting area adorned with classic chairs by Charles Eames and Mies van der Rohe.

‘The whole Cranbrook / Emigre revolution – I went totally against that,’ says Ongarato. ‘It wasn’t really my aesthetic. It wasn’t clear enough. It didn’t say things clearly or define things clearly. We started to do a lot of that clean, modernist style early on when the graphic environment out there wasn’t like that at all. But it caught up very quickly.’

Mary Libro and Jonathan Petley of Feeder, coming into design from a slightly different direction – Libro from digital imaging, Petley from architecture – have reached similarly restrained conclusions. They enthuse about the tactile qualities of their minimalistic designs with unabashed delight, but this sensuality doesn’t extend to their treatment of typography, which is set down on the page with deadpan, if not frosty, precision. ‘We always think of the idea first and then we play around with that until we bring it down to its essence,’ says Libro. ‘The images are beautiful. The information is pertinent,’ Petley observes of one of their pieces. ‘You don’t need anything more than that.’

While much of this neo-Modernist work is undeniably accomplished and projects a seductively fashionable air (at least for the moment), there is nothing specifically Australian about it. The argument is sometimes made that Australia, lacking much of a history, is intrinsically a modern – and therefore a Modernist – country. Wherever this aesthetic is applied, though, even in Europe where it originated, it now looks unimaginative and tired. Anything can potentially happen within the rectangle of the page or screen or billboard, so why default to such a predictable, aesthetically limited and culturally inexpressive range of possibilities? In discussion with Australian designers, it was surprising how many mentioned the old idea of the ‘cultural cringe’ – the anxiety that Australian culture might not match up to standards elsewhere. ‘There is still a lot of cultural cringe,’ says Penny Bowring. ‘There are still a lot of Australians who don’t have confidence in what we produce ourselves and will say that anything that’s international has got to be better than anything that’s local.’ It’s a moot point whether the Australian taste for neo-Modernism is an example of this, or just a sign that in an age of globalisation, everywhere is subject to much the same trends.

Prising open the spaces

Other Australian designers pursue paths that seem richer in both local and critical possibilities. Stephen Banham and Inkahoots, a Brisbane-based team committed to socially concerned design, are considered elsewhere in this issue. In Sydney, Advertising Designers Group has positioned itself as an ethical agency, producing carefully honed poster and advertising campaigns that help to raise awareness, cut costs and benefit society, the consumer or the environment. In Melbourne, Studio Anybody started five years ago with the intention of developing an alternative model of graphic design practice.

‘In focusing on concept-driven exhibitions, publications and installations, we hoped to develop alternative communication strategies, learn new skills, stay motivated and make people stop, laugh and reflect,’ explains Lisa Grocott, one of the five partners. Grocott, a New Zealander, teaches postgraduate design at RMIT University and her academic approach to professional practice remains the exception among Australian designers, though it is shared by the other four members of the team. They have managed to combine self-initiated projects with work for the Australian clothing label Mooks, as well as the Melbourne Fashion Festival.

The central question for Studio Anybody is to what extent it will be possible to find more hardnosed commercial clients who will permit an exploratory approach. The Dutch designers Armand Mevis and Linda van Deursen have visited RMIT and Grocott compares client cultures in the two countries. ‘When you listen to people like Linda and Armand talk about the way that they can push clients, you want to believe that’s possible here,’ says Grocott. ‘There’s no reason for us to pretend that’s just a Netherlands experience.’ Even so, she confesses to doubts, describing a meeting with a potential client who described a job as a ‘no brainer’ and who felt she was making a potentially lucrative commission more complicated than it needed to be.

Talking to Australian designers at all levels, it’s clear that design down under can no more be understood as a single kind of practice than it can anywhere else in the developed world. To compete at a high level for the biggest clients will require an increasingly focused approach, especially with the arrival in force of the global branding factories. ‘We have to be serious about our businesses and we have to have something to offer, otherwise they’re not going to take us seriously,’ insists Ken Cato.

There is no way that the smaller or even medium-sized local design teams will ever be able to outdo the globals, so perhaps the answer, as elsewhere, lies in a different strategy – locating the overlooked gaps and occupying them. This is what the most far-sighted and promising designers are doing. The future of Australian design, as an exploratory cultural practice, will depend on the success with which committed designers are able to prise open these spaces, negotiate relationships with sympathetic collaborators and offer alternative forms of culture that the big guns simply don’t grasp.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, London

First published in Eye no. 46 vol. 12 2002

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.