Autumn 1992

Reputations: Sheila Levrant de Bretteville

‘Diversity and inclusiveness are our only hope. It is not possible to plaster everything over with clean elegance. Dirty architecture, fuzzy theory and dirty design must also be out there.’

In 1990 Sheila Levrant de Bretteville became the new director of studies in graphic design at Yale University School of Art. Since the late 1950s, the Yale programme had been a bastion of Modernist theory, a conduit between designers in the United States and the programme in graphic design at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Basel, directed by Armin Hoffman. For more than 30 years, graduates of both programmes have profoundly influenced American design through both their professional work and their teaching.

Presiding over Yale’s long and productive history was Alvin Eisenman, whose retirement in 1990 prompted a committee of faculty and design alumni to appoint a new head, a decision which will shape the programme’s direction for the decades to come. The committee selected Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, who had attended Yale in the early 1960s and has since become an influential and outspoken designer and educator. As a feminist who participated in the rebirth of the women’s movement in the 1970s and its critical refinement in the 1980s, de Bretteville believes that the values culturally associated with women are needed in public life. She wants designers to begin to listen to different voices, and to forge more attentive and open structures to provide opportunities for others to be heard. She wants to move design towards proactive practice instead of focusing on corporate services.

While most faculty and alumni have supported de Bretteville’s inclusive definition of design, others have been outraged. Paul Rand, a member of the faculty since the late 1950s, resigned on principle, and encouraged his long-time colleague Armin Hofmann to do the same. In an angry manifesto published in the American Institute of Graphic Arts Journal of Graphic Design (vol. 10 no.1 1992), Rand railed against the violation of Modernism by screaming hordes of historicists, Deconstructivists, activists and other heretics. Behind each of these recent challenges to Modernism one can name a powerful woman whose voice threatens the stability of Rand’s carefully guarded ideals: behind Deconstructivism stands Katherine McCoy; and behind activism stands Sheila Levrant de Bretteville. Perhaps de Bretteville’s philosophy reflects an overall shift in the design profession, or perhaps it will be a catalyst for such a shift, just as the programme of Eisenman, Rand and Hofmann helped to redirect the currents of American design practice earlier in the century.

Ellen Lupton: How is the new programme you have instituted at Yale different from what preceded it?

Sheila Levrant de Bretteville: When you ask a question like that, I feel reluctant to locate the differences, because notions of ‘difference’ have been invested with so much positive thought on my part. Also, I have a great respect for Alvin Eisenman, and for the 40 years of work he did here, and for the intelligence and ecumenical spirit he brought to the endeavor.

But it is important to me that this programme be person-centred. The students are encouraged to put and find themselves in their work; my agenda is to let the differences between my students be visible in everything they do. In most projects – not just in thesis work – it’s the students’ job to figure out what they want to say. Emphasising the students’ desire to communicate, and focusing on what needs to be said and to whom they want to say it – that’s what I mean by person-centredness. While they may have existed before, it is even stronger now.

EL: Some faculty who were here for many years left in a spirit of protest. What resistance have you encountered from faculty or alumni or from your own students?

SLB: I think you should talk to the people who are upset. I am not upset. I am delighted. When students say they chose to come here because it scared them, because it was the most unfamiliar and most challenging programme, I consider that a positive place to start from (I think that comfort is a highly overrated emotion). It means they’re beginning a journey that allows them not to become representatives of a single, unifying, totalising view that would make all their work look the same.

I didn’t need to end anything that was happening here; I needed to add what I felt had been left out. There are people for whom diversity and inclusion are terrifying and inappropriate, and they have absented themselves from teaching here. I am hoping that the students who come here are attracted by the open-minded attitude and by the opportunity to frame their own way of being in the profession.

EL: Do you think people are surprised by what you have done?

SLB: Some people have said that I should be less visible, that I should be in the background, that I should simply and invisibly support the people who are here and whom I brought. But don’t those recommendations too closely match old female role notions?

In truth, as a woman designer, no one would have known about me if I hadn’t spoken out in the 1970s with a feminist reappraisal of the design arts. Focusing on one stratum of myself – gender – provided me with other ways to look at graphic design that anticipated the 1980s Deconstructivism critique of the International Style. I feel aligned with Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and other people who in the late 1960s and early 1970s were criticising the universalising aspects of design and the notion that there was one high, single truth that would improve the lot of everyone.

‘To be seen and not heard’ was not a good thing to be told. I was not told that by the majority, however, and I was not told that by David Pease, Dean of the Art School, who was 100 per cent supportive. The group of faculty and alumni that chose me, chose to send a signal to the design community about the kinds of changes they wanted to see at Yale. Since what I’ve done before is known, what I would do here can’t have been a total surprise. No one should be surprised that I would look at things from multiple perspectives, that I would be involved in the community or that I would care about the personal voice of the designer.

EL: What do you think are the most important intellectual tools for young designers today?

SLB: They need to learn about the different ways to interpret graphic design, the many different perspectives. Students should know the names and languages that go with each of these perspectives – not because jargon is useful, but because knowing about these issues enables them to participate in the debates should they choose to do so. I believe that a productive tension comes from diverse points of view, and that students should grapple with diverse points of view for any act of design.

We have given students readings from various critical perspectives, including psychoanalytic, semiotic, postmodern feminist and formalist. And we encourage them to take classes at the university, from people whose daily work is thinking from perspectives. Our students take academic courses every semester; it’s now a requirement. When I was a student here 30 years ago, we didn’t have seminars with readings that allowed us to discuss different perspectives. We took courses at the university, but bringing back that material to the act of doing, and thinking about, and writing about and analysing design didn’t occur in design seminars.

You asked about other kinds of tools. In order for designers to know whether the appropriate way of communicating to a particular audience is a poster, a billboard, an exhibition or an interactive hypermedia experience, they need to know what those tools can do. The choice of which format to communicate in should occur after you know whom you want to talk to, and what you want to tell them. This plays into our notion of proactivity, which is to go out into the commuity with issues that have meaning for you, find out who else is affected by these issues, what organisations already exist, what they are already doing, what needs have not been met and then look for what ways graphic design could communicate to those audiences who don’t have access to the information that’s out there for them.

EL: The person focus of your programme concerns not just the designer, but the audience. The audience has a new centrality.

SLB: That’s correct. Because the audience is not an audience; it’s a co-participant with you, and it’s also your client. You bring skills, they bring their own knowledge and you are both agencies of knowledge – your knowledge as a designer, their knowledge as a person in need and the community as a group of people in need. It’s a parallel construction rather than a top-down mechanism. The students here have had an experience of being alongside the client / audience / user, because they themselves are part of the group that makes up the client / audience / user.

EL: How does form-making relate to these problems of addressing an audience? You talked about the format, the institutional frame of communication. How do you fill up that frame?

SLB: I’m providing a variety of parallel experiences of coming to form. I personally believe in delaying form-making until you know what you need to say, to whom you need to say it and how it should be said. On the other hand, there is a hunger among our students for purely aesthetic exploration, where there is no need to communicate, where we take away the audience, where it doesn’t matter if we can understand it. We just play with the materials because we can bump into a new form of expression that we could apply where it’s appropriate. Pure aesthetic exploration of this kind is something I’m personally less comfortable with, so I invite people to teach here who are comfortable with it.

EL: In your 1983 essay ‘Feminist Design’ (Space and Society 6), you describe feminist design as a set of formal, tactical moves. What is ‘feminist design’?

SLB: First, what is feminism? In my understanding, feminism acknowledges the past inequality of women, and doesn’t want it to continue into the future. And the issue of equality broadens beyond women to involve the equality of all voices. Feminist design looks for graphic strategies that will enable us to listen to people who have not been heard before.

Thinking about myself from a gendered perspective – even if gender is a fiction – meant separating those experiences that relate to me as a gendered figure from other aspects of myself: from being from New York, being Jewish, being skinny. For me, the processes of childbearing, parenting and reading feminist writings brought social inequalities into sharper focus. There is a prevalent notion in the professional world that only if you have eight or more uninterrupted hours per day can you do significant work. But if you respond to other human beings – if you are a relational person – you never really have eight uninterrupted hours in a row.

Relational existence is not only attached to gender by history – not by genes, not be biology, not by some essential ‘femaleness’. A relational person thinks about other human beings and their needs during the day. A relational person allows notions about other people to interrupt the trajectory of thinking or designing – I used to call it ‘strudeling’, because strudel is a layered pastry. I don’t think strudeling is an exclusively female way of thinking, but I might call is a feminist way of thinking because to valorise this attitude is to separate it from gender and free it from the nineteenth-century notion that women’s culture belonged entirely to the private, domestic realm.

My grandmother, my mother, my sister and I all work. In my family, private and public spheres are not separated. I could easily take on the values of the work world, since I had to work, there was no choice. The kinds of work habits that art part of this public sphere – that deny relational experience – are precisely the ones I want to challenge. Feminism has allowed me to challenge them; thinking about myself as a woman has allowed me to challenge them. When women are in the workplace, women do as the workplace demands it. Part of feminism is about bringing public, professional values closer to private, domestic values, to break the boundaries of this binary system.

EL: In other conversations, you’ve used the word ‘care’ to describe feminist design. How is this relational spirit manifested in design?

SLB: In the early 1980s I came upon a set of strategies which I thought manifested that care. These include asking a question without giving the answer, so that viewers feel their own thinking is a value. Another strategy is to have multiple perspectives, which creates a tension that enables critical thinking in a viewer. Having the words and images contradict one another also creates a productive tension, by asking the viewer to resolve the conflict and thus bring his or her thinking process and point of view into play. Another principle is to be there in the street of your audience, who can give you feedback on how they understand it. Once you’ve experienced this, you are transformed in your notion of who the client is. Last year a group of our students designed a pro-choice billboard for a course taught by Marlene McCarty and Donald Moffett. (Marlene and Donald work together in the design studio Bureau, and they’re members of the AIDS activist group Gran Fury.) They gave the students a newspaper and asked them to locate an issue they felt was important. A group of students who chose reproductive rights analysed US laws, looked at what local and national organizations are doing, and finally decided to provide a fact: ‘73 per cent of Americans are pro-choice’. By providing a statistical fact that most people didn’t know, they would allow viewers to think that perhaps they were being manipulated by media coverage of pro-lifers.

EL: The formal language of the billboard is the expected language of mass media. It doesn’t have a ‘design’ look.

SLB: That’s intentional. The students didn’t want the aesthetic position to be the primary reading. They don’t want you to think how nice it looks and wonder who designed it before receiving the information.

EL: A lot of contemporary writing about design, especially writing influenced by postmodernism and contemporary literary theory, suggests that when images and messages become completely layered, a political challenge occurs, because the design forces the viewer to discover the meaning. In the situation you’ve just described, a decision was made to be clear and direct. What do you think about the aesthetics of complexity?

SLB: These ideas are not mutually exclusive. On a billboard, which you have about three seconds to understand, a caring and inclusive design strategy can only be enacted in certain ways. On the other hand, when there’s more time for the audience to be in front of the design communication, then more complex strategies that provoke a thinking audience to fell and resolve the tension are appropriate.

EL: A lot has happened since you studied at Yale 30 years ago – the protest movements of the 1960s, the feminist revolution of the 1970s, the theoretical research of the 1980s. How have the conditions changed that once made Modernism seem viable?

SLB: I will never, never, never forget to include people of colour, people of different points of view, people of both genders, people of different sexual preferences. It’s just not possible any more to move without remembering. That is something that Modernism didn’t account for; it didn’t want to recognise regional and personal differences.

People who have given their whole lives of supporting the classicising aesthetic of Modernism feel invalidated when we talk about the necessary inclusiveness, but diversity and inclusiveness are our only hope. It is not possible any more to plaster over everything with clean elegance. Dirty architecture, fuzzy theory and dirty design must be there.

EL: Many younger women are afraid of the word ‘feminism’, though they might support its principles. You’ve suggested that feminism is not just for women, but that it’s an attitude for including everybody. Do you think that feminism could be a design philosophy for the 1990s, an aesthetic and ethical attitude that could help fill the void left by Modernism?

SLB: I believe that gender is a cultural fiction, not a biological given. But while there have been many achievements in the last 20 years, racism and sexism are still rife. Some responses to my presence here really do come because people attach what I do to the fact that I am a woman. Those things have to become detached. But until we are able to detach gender from the ways we are in the world, it’s important for us to move towards equality. Moving towards equality is what the word feminism means. Until we’ve achieved that, we can’t give up the word. Feminist design is an effort to bring the values of the domestic sphere into the public sphere; feminist design is about letting diverse voices be heard through caring, relational strategies of working and designing. Until social and economic inequalities are changed, I am going to call good design feminist design.

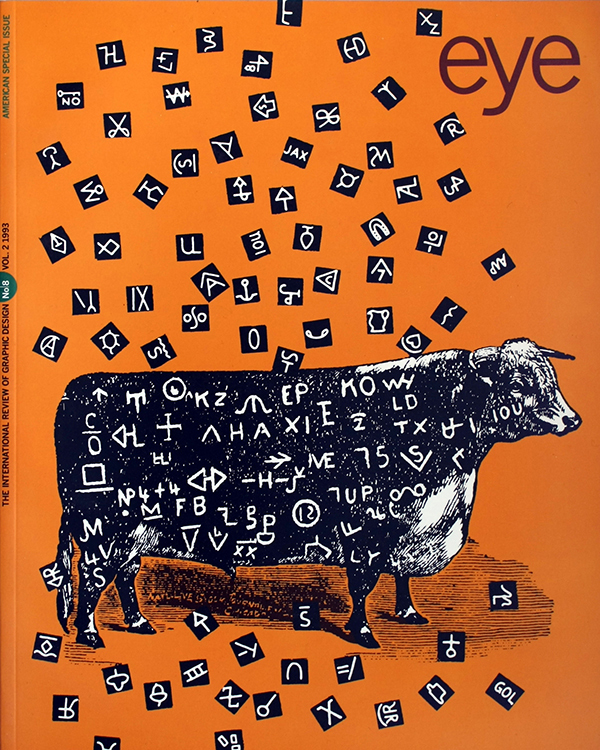

First published in Eye no. 8 vol. 2 1993

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.