Winter 1999

Surface wreckage

anonymous designers

Robert Brownjohn

Walker Evans

Herbert Spencer

David Carson

Jean Baudrillard

Three books showing accidental collages of torn posters an other random marks revive interest in a style of image-making drawn from the city streets

Jonathan Miller has an international reputation as one Britain’s most versatile figures in the arts. He qualified as a doctor, came to fame as a satirist and performer, directed a television film of Alice in Wonderland, and wrote a study debunking Marshall McLuhan. His thirteen-part TV series on the history of medicine, The Body in Question, is a milestone. In his spare moments, he has directed more than 50 opera productions in London, New York, Paris, Florence and Berlin.

What we didn’t know, until the publication of a new book, is that for nearly 30 years Miller has used a cheap automatic camera to take photographs of details – ‘pictures of bits’ – in the street. Nowhere in Particular shows dozens of images of torn, scuffed, battered, rusted, cracked and peeling surfaces. Miller describes them as ‘negligible things to which one would normally pay no attention at all. Nevertheless,’ he continues, ‘these fragments and details attracted my eye and I felt the irresistible urge to record them.’

Jonathan Miller, undated, untitled photograph, published in Nowhere in Particular, 1999.

In his introduction, he draws comparisons with the scenic details painted around the year 1800 by artists who felt them worthy to be pictures in their own right. This is interesting, but gives no hint of the contemporary context for an activity that Miller seems half inclined to play down as ‘random scavenging.’ What he doesn’t mention is the degree to which such ‘bits’ have seduced many artists, photographers and designers in the twentieth century. The torn posters on the cover of his book – one face appears almost to be dreaming the other – belong to an established, though admittedly off-beat, genre of image-making. Part of the fascination of Nowhere in Particular lies in observing this way of seeing being pursued for many years, almost obsessively, by a casual, non-professional photographer with no immediate artistic use for the images in mind.

The American photographer Walker Evans was one of the first to focus on street posters and signs as sources of insight into the society that created them. In Torn Movie Poster, taken in 1930, the movie stars’ glamorous heads are divided by a gash that begins in the top right corner and narrows to a fissure across the starlet’s face. Evans’s tight close-up excludes most of the poster because it is the fault-line destabilising the image that he wants us to see. In Minstrel Showbill, Alabama, taken in 1936, he shows the entire poster, with some of the surrounding wall. This time, a much greater proportion has been torn away and the bricks are re-emerging from behind a patronising scene of ‘comical’ black folk running round a yard. The abrasions of the elements, assisted perhaps by the hands of passers-by, strip away a dubious message.

Walker Evans, Minstrels playbill, Alabama, 1936.

The idea that mangled street posters might be physically appropriated for artistic purposes is attributed to Léo Malet, a French poet, who was briefly a member of André Breton’s Surrealist group. In the mid-1930s, observing the processes by which pristine printed images were transformed, Malet proposed a new form of Surrealist street poetry shaped by chance. ‘Soon,’ he wrote, ‘collage will be executed without scissors, without a razor, without paste . . . Abandoning the artist’s table and his pasteboard, it will take its place on the walls of the city, the unlimited field of poetic realisations.’ Commercial artists would supply the raw materials and passing pedestrians, aided by wind and rain, would intervene to unlock new meanings never intended by the designers, as fragments of earlier images, hidden below the top poster, were once again exposed to view.

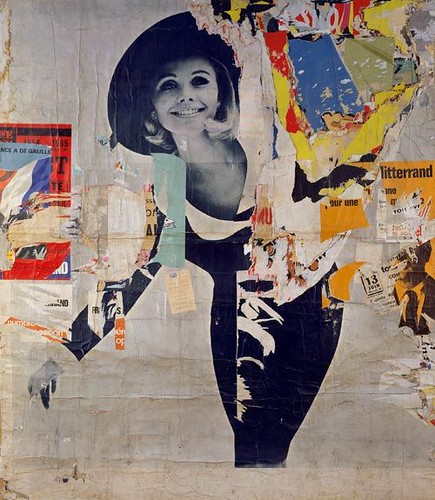

Malet’s idea of décollage remained a theory until the 1950s when two French artists, Jacques de La Villeglé and Raymond Hains, began, unknowingly, to put it into practice. Hains was unhappy with the black and white photographs he had been taking of torn posters and decided to pull down these ready-made collages and take them home. He later moved on to other forms of artistic practice, but Villeglé – a mixture of artist, collector and documentarist – stayed loyal to this way of working for his entire career. Each piece would be titled with the place of discovery, the month and year – Windsor-Cinéma, February 1959, Boulevard Richard Lenoir, 22 September 1964, and so on. Cut loose from their original poster sites, mounted on canvas and displayed in the quiet of the art gallery, they have enormous gestural energy and an aesthetic power that comes from endless, unpredictable collisions of colour, ragged line, word-shape and image.

To describe the random forces that brought these images into being, Villeglé coined the term Lacéré Anonyme. He saw this ‘anonymous lacerator’ as the mythic embodiment of the crowd’s anarchy and dissent as it defaced every attempt at persuasion by commercial and bureaucratic authorities. His own modest role was to act as curator and select singular specimens from the lacerator’s vast oeuvre.

Jacques Villeglé, Rues Desprez and Vercingétorix – The Woman, décollage, 12 March 1966. Museum Ludwig.

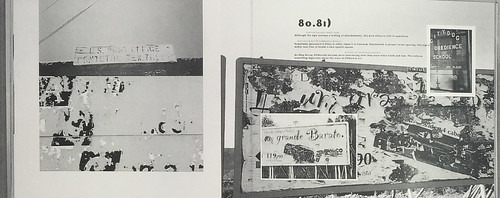

For designers, the public fate of their efforts offered a spectacle both peculiar and fascinating, as dreams of abundance were reduced to images of transience and decay. In the early 1960s, while Hains, Villeglé, Mimmo Rotella, Asger Jorn and other affichistes wrenched posters from the hoardings, Herbert Spencer was documenting these chance depredations with his camera. In his pictures of ‘strange juxtapositions revealed through the sad ribbons of torn posters’, he seems almost to delight in recording the dissolution of an order he spent his days as a designer attempting to impose. His photographs of broken shop-front lettering, scarified posters and graffiti-pocked walls disclose an urban panorama in which signs of official communication have frayed into an impromptu poetry of tattered logos, shattered copylines and stuttering letterforms. In a picture of a St. Pancras street, the one-way sign is sucked in and nullified by a churning backdrop that, if it weren’t for a Heinz label, would feel closer in mood to an Abstract Expressionist daub by Robert Motherwell than an ad.

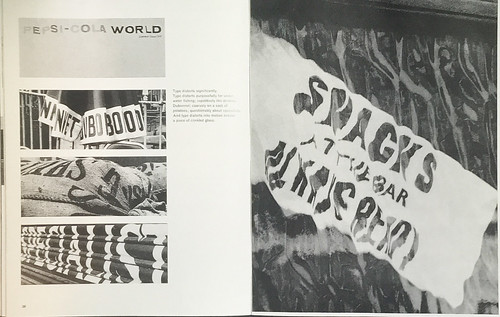

Designers were quick to see that the street’s haphazard visual fabric could be used as inspiration for new kinds of design. In 1961, the most concentrated analysis of these possibilities came from Robert Brownjohn, an American designer then resident in London. Brownjohn’s photo-essay ‘Street Level’, for Herbert Spencer’s Typographica magazine (see Eye no. 31 vol. 8), has 31 pages of his pictures taken on a single trip around the city. They catalogue irregular word spacing; missing, misaligned, eroded and overlapping letters; handwritten signs; type distorted by glass. ‘The things they show have very little to do with Design, apart from achieving its object,’ Brownjohn notes (my italics). ‘They show what weather, wit, accident, lack of judgement, bad taste, bad spelling, necessity, and good loud repetition can do to put a sort of music into the streets where we walk.’

Robert Brownjohn, spread from ‘Street Level’, Typographica new series no. 4, December 1961.

By displaying professional design projects next to samples of primitive and accidental street typography, Brownjohn transformed an ad hoc way of seeing common to many designers into a manifesto for purposeful scanning of the street. In the years that followed, a ‘street level’ sensibility and fascination with vernacular design became one of the cornerstones of experimental graphics. From the late Swiss typographer Hans-Rudolf Lutz (see Eye no. 23 vol. 6) to David Carson, designers embraced the street’s disorder as an alternative ordering principle in their work. The camera continues to be an essential tool for gathering these treasures, especially when travelling abroad. In 1991, Lutz published a photo-essay, ‘Graphic Design as a Live Art’, based on photographs of South American streets. In some of his most arresting examples, the same found poster image of a grimacing woman in glasses is shown six times, each example subject to a different type or degree of environmental attrition.

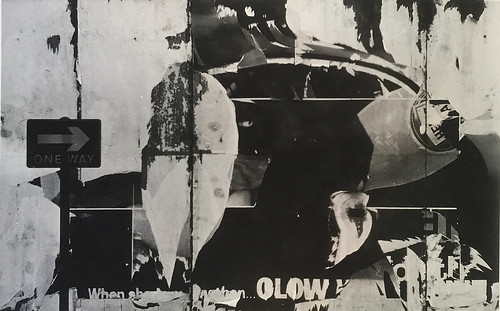

Carson has sometimes noted his aesthetic debt to Lutz, and in his lectures in the 1990s he showed slides of peeling posters seen on walls in Mexico and elsewhere that inspired his own typographic method. He didn’t necessarily import these images directly into his designs any more than Brownjohn and his colleagues had done 30 years earlier. Usually, it was a matter of allowing the shapes and colours to percolate in his mind, and then devising combinations of type and image with similar qualities of randomness, unpredictability and ambiguity. As Brownjohn expressed it, with laconic precision: ‘Bad word spacing can happen. Or it can be designed.’

David Carson, spread incorporating the designer’s photographs, published in Fotografiks, 1999.

Why do images of torn posters and damaged signs exert such a powerful hold? And what is it that distinguishes one specimen of ‘chance art’ – as Herbert Spencer called it – from the next? ‘The fact is, most of the torn posters or hand-lettered signs that I come across are not interesting,’ Carson told an interviewer. ‘But every now and then, the elements come together in a way that I find pleasing . . . and that’s totally subjective and intuitive or my part. I’m not sure I understand myself what makes one thing visually interesting to me, while another strikes me as being just ordinary.’

What is so striking about Jonathan Miller’s ‘negligible’ images is how aesthetically resolved, how right to the eye, they seem. They are compelling as a collection, but many stand up in their own right. Miller and his designers have taken a number of decisions that intensify their impact. The majority are shown same size as the original prints and, except for a few full-bleed pages, most are surrounded by white space. There are no page numbers or captions and Miller makes no attempt to give their origins in time and location (hence the title: Nowhere in Particular) although there are sometimes internal clues. The unanticipated colour changes produced by a cheap developing process – Miller, like Carson in his new book Fotografiks*, used an ordinary snapshot service – introduce a further element of chance and level of disassociation from the original scene. ‘In the final outcome,’ says Miller, ‘I preferred what I got to the picture I thought I was taking.’

Herbert Spencer, St Pancras street, 1960s.

For Miller, these images are ‘abstract designs’ drawn from the wreckage of real surfaces, but even at their most abstract they are still artificial constructions readable as traces of the people who made them and viewed them, an unseen but persistent presence. That they offer documentary evidence of things no longer working or wanted, of demolition and undoing, of entropy at large in the world, only adds to their poignancy (Spencer’s ‘sad ribbons’). Where fragments of people are glimpsed – an arm, an eye, a pair of lips – this sensation is even more acute. In one picture, a man’s face has been neatly excised, leaving only an immaculately combed head of hair. Among the torn edges of his new face is the sharp form of an uppercase ‘A’, a visual rhyme with the triangular shape of his hairline and brow. Whoever he was, whatever he was trying to tell us, he has become ‘Exhibit A’ in a case that will never be solved.

‘Every photographed object,’ writes Jean Baudrillard, ‘is merely the trace left behind by the disappearance of all the rest. It is an almost perfect crime, an almost total resolution of the world, which merely leaves the illusion of a particular object shining forth, the image of which becomes an impenetrable enigma.’

Jean Baudrillard, Venice 1989, published in Photographies 1985-1998, 1999.

In characteristically ecstatic language, Baudrillard comes closest, perhaps, to capturing the magnetic lure of the torn poster image. In an essay prompted by his own activities as a photographer, he reflects on the ‘dizzying impact’ and ‘magical eccentricity’ of the perpetual photographic detail, and on the world’s refusal to yield up its meaning in photographs. Discontinuity and fragmentation are inescapable conditions of photography, and if this is always a factor drawing us to a photograph – any photograph – then the torn poster photograph carries a double charge. In its ravaged paper surface, an inherently discontinuous medium finds a perfect, enigmatic match.

* Jonathan Miller. Nowhere in Particular. Mitchell Beazley, 1999

* David Carson. Fotografiks. Text by Philip B. Meggs. Laurence King, 1999

* Jean Baudrillard. Photographies Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz, 1999

First published in Eye no. 34 vol. 9, 1999

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.