Winter 1993

Talking pictures

The comic book speech bubble has evolved into a highly expressive form of vernacular lettering

There is a vernacular alphabet in existence which, for want of a better name, could be called standard comic book lettering (SCBL). Although little more than a set of irregular, hand-rendering letterforms arrived at through consensus rather than design, SCBL has become a key part of the graphic language of the comic book. Shaped by tradition, editorial direction, the need for the appearance of consistency within the major comic book publishers’ house styles and by the action of the letterer’s pen or brush, SCBL plays host to the range of variations that might be expected in any handworked artefact and yet remains recognisable as a generic form by dint of its fluidity and rhythmic regularity. Anything from Marvel or DC Comics has all the ingredients of this idiomatic but usually unremarked style.

As a rule SCBL has bounce and elasticity – it is open faced, instantly legible and easy on the eye. These qualities are obtained in part by the consistent use of uppercase characters, some of which are emboldened or slanted to emphasise the cadences of speech and narrative rhythms. The letterforms are automatically kerned by the movement of the letterer’s hand, so SCBL never suffers from the machine quality of other printed matter. The rhythm of the letters within a speech bubble incorporates small fluctuations in style which give a well-lettered page an essentially human quality. Letterers are usually credited in the standfirst, but the demands of the genre and expectations of the audience have meant that until recently they have suffered from a lack of recognition for their individual skills and from the notion that they are interchangeable.

The consolidation of SCBL as a recognisable style can be traced back to the production methods introduced by comic book publishers in the US in the years after the Second World War. Traditionally the comic strips from which comic books were to develop were drawn and lettered by the same person. Rudolph Dirks’ “Katzenjammer Kids”, George Herriman’s “Krazy Kat” and Chic Young’s “Blondie” were all lettered by their artists, and in Herriman’s case in particular, the letterforms were wedded stylistically to the way the strip was drawn, lending the whole a personal and authorial tone.

The practice of producing comics by assigning the various tasks involved to interchangeable teams of inkers, colourists and letterers dates from the heyday of the comic book in he US in the 1960s and 1970s. Marvel mania an equally avid following for the rival DC offerings meant that the sheer volume of books required to feed a hungry market demanded the drafting in of teams of workers and the setting up of a form of production line. The homogeneous graphic language of the comic book was created to a large extent by these working methods. The role of the letterer was to provide a blank, instantly recognisable voice for the tight and communicative scripts of writers and artists.

The comic book letterer not only produces the SCBL used for speech and thought, but also provides onomatopoeic “shocks”. To produce lettering for speech bubbles and captions requires discipline and, at times, a smoothing out of the quirkier elements of the individual hand, whereas sound effects and character logotypes give letterers the opportunity to exercise a degree of inventiveness and self-expression. A memorable or communicative logo for a Shadowhawk or some other costumed hero can help to define the character in the reader’s mind. Likewise, a convincingly sonic “Shlakaboooom!!”, delivered with the right degree of flourish, can lift a story and make a page visually engaging.

Some of the best examples of the letterer’s art can be found in Howard Chaykin’s American Flagg, lettered by Ken Bruzenak. Flagg first appeared in 1983 under the First Comics imprint, and was something of a turning point in redefining the scope of the letterer’s role and the quality expected of comic book lettering. Part of the reason for the freedom and invention of Bruzenak and Chaykin’s work lies in differences in the way full-colour artwork is produced. In the UK, effects are drawn on to overlays or lettered and dropped in after inking – the stage where the forms are fleshed out with their body colours – whereas in the US letterers often work straight on to the board prior to inking. The quality and impact of sound-effect lettering, which as a “dead area” around the world where it has been dropped in, are markedly weak in comparison with the engaged fluidity of Bruzenak’s work. Having the letterer work straight on to the board allows the letterforms to be pierced by pictorial elements and to respond to the action. The dramatic licence and freedom of character produce what amounts to a handworked set of mutating fonts which long predated computerised equivalents.

The form and content of the comic book have changed dramatically over the last 25 years. With the advent of the graphic novel in the mid-1980s, the medium embraced ever more ambitious subject matter. Pages within the best graphic novels from this period resemble deconstructed, chaotic storyboards as writers and artists, editors and art directors took Chaykin and Bruzenak’s ideas still further and used the page in ways which broke away from the rigid predictability of traditional structures. In an echo of the desire of writers such as Grant Morrison, Alan Moore and Frank Miller to layer communication, letterers such as Gaspar Saladino, Jim Novak and Todd Klein have sued letterforms as aids to characterisation and transmitters of sophisticated meanings beyond language and dialogue.

In Grant Morrison and Dave McKean’s dark knight drama Arkham Asylum, Saladino uses deafly rendered uppercase SCBL with traditional emboldening and slanting for the Batman, acknowledging the conventions of the costumed superhero genre. Other letterforms, both in and out of speech bubbles, work to refine and reinforce characterisation. For example, the personal recollections of Arkham, the principal narrative voice, are given in a form of regular handwriting with a scripted slant, while the various voices of madness within the asylum are rendered in idiosyncratic and highly individual letterforms. The speech of a god-like figure uses a pseudo-Greek font, while the Joker – the central protagonist and the Batman’s arch enemy – is shown to be obviously and dramatically mad by the freeform, blood-red, blotched and scratchy letters in which his outpourings are rendered. Saladino’s previous work with Jim Novak on the series Elektra Assassin also employs a range of techniques which bring back the personal and artistic quality that was largely lost at the point where lettering moved into the realm of the production line. Higher audience expectations have created space for the letterer to become more than an unsung functionary.

The potential for the use of computer technology in comic book production is still not fully realised – at present only colouring is computerised on a wide range of titles produced in the US. But new technology does provide scope for the development of an approach to the letterform that is flexible, user-friendly and which maintains the organic nature of the comic book page in a way that typesetting within the irregular ellipses of the speech bubble would not. Rian Huges is a British typographer and artist working within the comic book genre, principally with Grant Morrison for Fleetway’s UK-based title 2000 AD. After nearly a year of Macintosh ownership, he is firmly of the “computer as personal liberator” school of thought, an can foresee the death of hand-rendered SCBL at the hands of computerisation.

“The Macintosh could and should alter the character of the comic strip by placing more of the disparate aspects of production back in the artist’s control,” says Huges. “European and particularly French comics are usually lettered by the artists themselves in a sympathetic and unique way. What I would like to see is the Macintosh enabling artists with terrible handwriting to letter their own work and so incorporate lettering more fully, perhaps in a manner similar to Eisner’s “The Spirit’.”

Influenced by Europeans such as illustrator Ever Meulen, Hughes favours an integrated approach to the comic book page, though the evocation of Will Eisner and his extraordinarily inventive use of lettering, logotypes and typography in his “Spirit” strips of the 1940s might place too great a burden of expectation on the powers of the Macintosh. To date, Hughes’ strategy for integrating artwork and type has been to come up with typefaces which work within the medium precisely because they mimic at least some of the random character, dynamism and fluidity of hand-lettering.

The desire to find an integrated, personal and sympathetic voice for the contemporary comic book, and to exploit the continued adult interest in the medium which developed with Robert Crumb and the underground presses of the 1960s, has led to the emergence of the confessional comic. America’s Joe Matt and Daniel Clowes base their narratives on what appear to be condensed version of real-life experiences, all of which have an uncomfortably close ring of truth about them. The intimate and everyday nature of the confessions is tin sharp contrast with the histrionics and flashy glamour of, for example, Richard Starkings’ work on Marvel’s Sabre Tooth. In Joe matt’s comics, dense pages of black-inked text outweigh the drawn images. Matt’s lettering pays lip service to convention – it is all rendered in straightforward uppercase and there is the usual use of emboldened words to stress key ideas, with the occasional dramatic intervention to disrupt the even flow of letters across the page. But the tone of the narrative and the kind of letters used to transmit the idea of a cartoon diary – close-set, requiring close reading – draw the reader into the drama, producing an effect of intimate engagement with the hand and mind of the author. The same is true of art Spiegelman’s Maus. The idiosyncrasies of the author/artist’s lettering style – leaning mostly left, right for emphasis – give the narrative a personal voice that SCBL would be simply unable to achieve.

In the comics produced by the punkish alternative fringe, the letterer’s art comes full circle. As with George Herriman, working between the wars, there is a close fit between the artists’ styles of drawing and lettering. Here, the mainstream conventions of SCBL dissolve in a welter of styles – and voice – as personal, varied and unpredictable as handwriting itself. In publications such as Hard-Boiled Defective Stories, Philadelphia-based artist Charles Burns subverts the routine histrionics of SCBL by employing a version drained of all expression; by declining to play up the action, the deadpan speech bubbles throw the weirdness of his characters and storylines into even higher relief. In other American strips, such as those drawn, written and lettered by Gary Panter, Mark Beyer and Jonathan Rosen, the lettering is not much different from ordinary handwriting somewhat ineptly rendered; the effect is to imbue their strange narratives with an air of claustrophobic obsession.

Michael Horsham, design historian, London

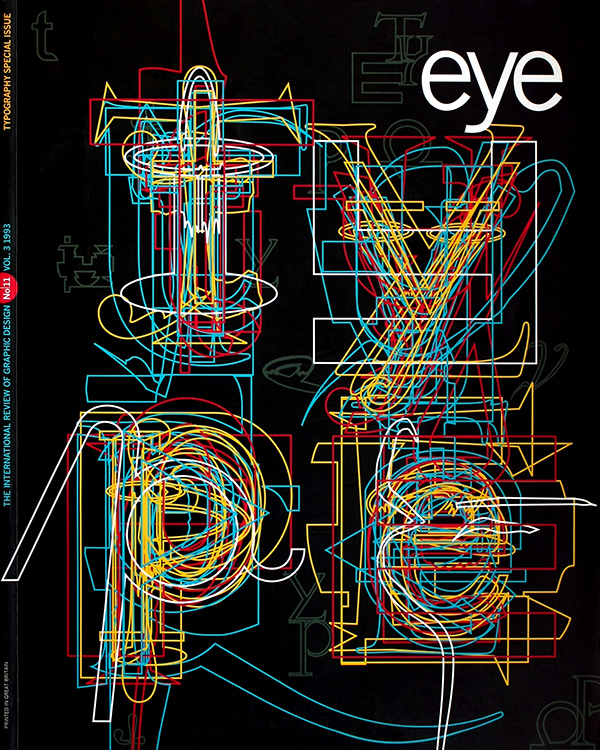

First published in Eye no. 11 vol. 3, 1993

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.