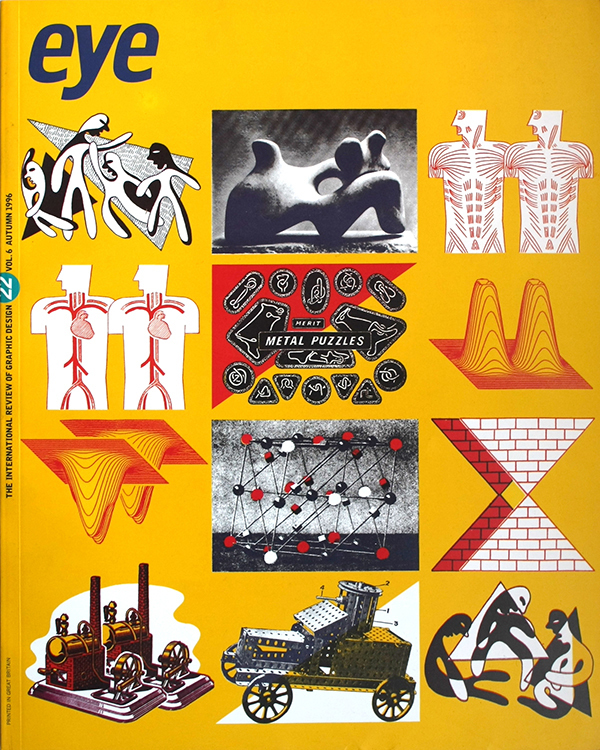

Autumn 1996

This signifier is loaded

Zurich designer Cornel Windlin is a fluent graphic stylist and a playful manipulator of communication codes

Signifiers don’t come much more heavily loaded than Cornel Windlin’s posters for the Rote Fabrik, a performance space located a couple of kilometres south of Zurich’s city centre. Windlin’s first public communiqué, based on a firing-range target, rounded up concert-goers with a pistol-brandishing silhouette. If this suggested the arrival of a designer who, conceptually at least, should be regarded as armed and dangerous, it paled beside a later creation, in which Zurich’s good townsfolk were treated to a scarily alluring Uzi, presented against a brilliant yellow background.

It is easy to see how such hair-raising visual tactics might have come as a jolt to the peace-loving collective that operates the lakeside centre, set up fifteen years ago to mollify Zurich’s young people in the wake of city riots. Windlin is sure the automatic weapon poster lost him the job (though enquiries suggest this was not the case). But the willingness – or need – to believe the worst says something in itself. Client relationships are always distinctly uneasy for Windlin. ‘It’s always a problem,’ he says, ‘If I’m lucky I can get away with things – if it’s a good client. If it’s a bad one, then I’m the one who’s going to walk away with the money, but I’ve lost the fight somehow. I don’t seem to fit in. I don’t seem to find people who are willing to do what I want to do.’ When he won a prestigious Swiss prize for the applied arts in 1995, he illustrated his citation with a prostitute card that read, ‘I’m young, naughty and need to be punished.’

Looking at the range, consistency and power of Windlin’s work since he returned to Zurich in early 1993 confirms the impression of a designer for whom dissatisfaction may just be a natural state. It is hard to imagine many London-based venues or arts organisations sanctioning the sustained vernacular experiments conducted in his 33 concert posters for the Rote Fabrik (Red Factory), or allowing anything as graphically adventurous and resolutely unpopulist as his exhibition posters for the city’s Museum für Gestaltung. Yet Windlin worries. He worries that Zurich might be too small, too parochial, too cosy and that the Rote Fabrik series, meant for a particular audience, might not work out of context, or seem very interesting. But most of all he worries about what to do next: ‘What is there to say?’ he asks. ‘What do you have to say? And how do you do it?’

Now 32 [in 1996] Windlin belongs – like British colleagues such as David Crow and Ian Swift – to a mid-1980s generation attracted into the profession by the pop-culture triumvirate of Neville Brody, Peter Saville and Malcolm Garrett. ‘I was very interested in music,’ he says. ‘I still am. And a lot of graphic design that was new and fresh was associated with music. It came on record sleeves and it came primarily from England.’ An unsatisfactory interlude in a Zurich advertising agency as designer and copywriter, as part of his studies at the Schule für Gestaltung in Lucerne, confirmed his aptitude for language, while convincing him that he wasn’t the agency type. In the summer of 1987, he completed a second placement assisting Brody in his Tottenham Court Road studio and returned in late 1988 to take up a full time position at the designer’s new East London base.

Windlin gained invaluable experience helping Brody on projects for Nike, Swatch, London’s Photographers’ Gallery and the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, a cultural institute in Berlin. But everything inevitably left the studio with the design star’s value-conferring signature on it and Windlin faced the usual assistant’s problem of establishing himself as a designer in his own right. After taking the decision to leave the studio in 1990, he put in the best part of a year as art editor at The Face – the magazine was going through a period of awkward transition – then went freelance. ‘I did get work immediately,’ he says, but it was a very difficult time.’

Up to this point it would be fair to say that Windlin was a designer of promise who had never quite found the setting to give of his best. When he decided to return to Zurich it was for personal reasons rather than a strong desire to go back. Three and a half years on, securely established in studio space at the offices of Parkett, the Swiss art magazine, he seems thoroughly disenchanted with the city. Yet within Zurich’s bourgeois precincts – ‘It’s like being in a model town,’ he complains – he has found the freedom to create a body of work that has rapidly marked him out as one of the most thoughtful and original young graphic designers working in Europe in the 1990s.

One of Windlin’s first initiatives was to start his own dance music club, Reefer Madness, with a couple of friends. In the membership cards and flyers he designed for the club’s monthly gatherings, be began to play referential games with everyday graphic language and this approach became the mainstay of the posters that Reefer Madness co-founder Bernd Blankenberg began to commission a year later, as concert organiser for the Rote Fabrik.

Windlin’s problem with each of the Rote Fabrik posters was to find a way of announcing four or five concerts by musicians playing wildly different styles. Sometimes the choice of visual theme relates directly to one or more of the artists – as with the April 1994 firing range target. ‘Violence and guns are very present in hip-hop lyrics and the whole culture of hip-hop,’ explains Windlin, whose use of gay icon Rock Hudson on another poster was a similarly pointed allusion to hip-hop’s homophobia. More often, though, there is no direct link between the chosen imagery and musicians.

Windlin’s response to an open brief has been to create what is, in effect, a library of vernacular references. The posters, usually printed in runs of 2000, take their graphic form from hazard warning labels, newspaper lonely heart ads, holiday postcards, Hollywood star portraits, doctrinaire Swiss Modernism, and the ‘big idea’ – though there is a larger sense in which the series as a whole might be considered as an example of a conceptual graphics that relies for its effect on the regular audience’s awareness of the unfolding image play. Contemporary styles are similarly appropriated, with several posters based on expressionistic type manipulation, whether by the Macintosh or by hand.

Appropriation, in the postmodern sense, seems the best word for what Windlin has done. His purpose isn’t parody – there is no intensification of distortion for satirical effect – and his method is too forensic in its analysis of the precise nuances of the original to be dismissed as pastiche. The Rote Fabrik series is quite different, for instance, from US designer Charles Anderson’s construction of an idealised ‘bonehead’ Americana out of the mid-century commercial vernacular. On the other hand, as with Anderson, the sources have been unmistakably tweaked in the process of acquisition. Windlin’s ‘Designers Republic’ is more accomplished than its inspiration (a Joey Beltram CD) and easily the equal of more elaborate DR pieces.

On one level, these posters could be considered as finger exercises, with Windlin emerging as a craftsman of unusually versatile technique. He himself compares the series to a student project: ‘There were a lot of things I wanted to do, that I had to get out of my system. It’s also about excitement for myself.’ Invocations of postmodernism succeed only in reducing him to silence. ‘If I think about postmodern architecture, for instance, it just makes me cringe, it makes me want to say I haven’t got anything to do with that. It certainly goes beyond simple plays of style, appropriations.’ He is not particularly concerned, though, by whether the viewer succeeds in penetrating the referential image-play or not. For Windlin, the stylistic sleights of hand seem, more than anything, to be ways of avoiding what he regards as the ‘trap’ of personal style.

His undogmatic talent for discovering appropriate form is seen to more directed effect in projects for Zurich’s design museum. In a poster for the exhibition ‘!Hello World? Internet Privat’ – about digital communication with strangers – a bra-clad girl displayed in her boyfriend’s homepage becomes a poignant and at the same time ambiguous icon for the public disclosure of private self-image. The girl’s pixelised body is overlaid by sampled images of cats (one squashed by a car) and dense fields of electronic interference which intensify the sense of voyeuristic compulsion. Another Museum für Gestaltung poster for the exhibition ‘Zeitreise’ (Journey through time) finds an almost mystical metaphor for dreams of escaping time using technology in the chance encounter of a bicycle wheel and a jet of water from a public drinking fountain as it overshoots the basin.

Windlin speaks warmly of the museum’s director, Martin Heller. ‘He’s a client who’s not against you – which is very often the situation. He understands and he’s on your side, but he also has his own agenda, so it’s a really interesting collaboration.’ Heller for his part regards Windlin as a conceptualist of unusual ability.

Windlin’s relationships with commercial clients have been less happy. A retail identity for a new youth department at the Globus department store on Zurich’s well heeled Bahnhofstrasse was cancelled the day before its official opening when the shop started to have belated misgivings (in a city notorious for its drug problem) about Windlin’s modest proposal for the department’s name: Overdose. In London, a billboard concept for Foster’s Ice Beer, aimed at 18-24-year-olds, began as a typographically brutal restatement of the advertiser’s brief – ‘Approachable – irreverent – dangerous – great taste – Ours! (humour, “go for it”)’ - and was watered down into harmlessness. Perhaps the most surprising aspect of these outcomes is that Windlin himself seems quite so surprised by them.

For a designer with such a strong drive to express his own criticisms of the communication processes he is commissioned to serve, these might seem to be highly unpromising choices of client. ‘What I do find a problem, more and more,’ agrees Windlin, ‘is that all the time I’m solving other people’s problems and arranging someone else’s work. That’s not terribly exciting for me and I’m not very good at it.’

The Swiss typographer Hans-Rudolf Lutz (see Eye 23), his former teacher and continuing mentor, advises Windlin to follow his own example and go into teaching, using the hours that remain to work on his own projects. This would offer a time-honoured solution to his need for conditions in which self-authorship might flourish, but Windlin prefers to test his mettle in the marketplace and resists such an arrangement as too big a compromise. At the same time, he pinpoints a dilemma facing any would-be experimentalist dependent on the whims of commerce. ‘In graphic design, if you are trying to push the boundaries, it seems you end up being a laboratory rat for new aesthetic forms. And as soon as they’re seen as probably successful in the marketplace, people can adapt them and do it themselves.’ What Windlin needs now is to find or create a position where he can run his own lab.

First published in Eye no. 22 vol. 6, 1996

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.