Autumn 1990

TV in the age of eye candy

People used to say the ads were the best thing on British TV. Now it’s the graphics which are overwhelming the programmes.

With its usual succinctness, the design commentator Peter York summed up what has happened to British television graphics when he appeared on the BBC2 arts programme The Late Show last year to talk about the history of station identities. “Design comes to us all in the end,” he intoned rather dolefully as he pondered the latest big-budget high-tech corporate identity package put together by English Markell Pockett for the commercial ITV network. York’s world-weary air revealed as much about what he thought about the subject as what he said. Design, it implied, had finally come to TV, but it was all so late in the day.

He had a point, but it needed qualification. After all, for as long as there has been TV, there has been some form of TV design. Today’s designers talk with respect of the work of pioneers like Bernard Lodge, who produced the titles for the first Doctor Who series in the early 1960s and was one of the first to take TV graphics away from film and conventionally painted artwork to using video effects.

But in the last five years, something new has arrived on British screens: Design with a capital D. For a start, there is so much more of it – not just titles and channel identities (idents), but previews, menus, alternative versions of the idents and all manner of ambient blips seem to have materialised to fill any dead air that might still lurk in TV’s twenty-four-hour stream of images. Following the success of graphics-laden youth series like Network 7, design has even colonised the programmes themselves.

TV design in the 1990s looks very different. The development of computerised post-production technology like Paintbox and Harry has radically increased the kinds of visual effects available to designers. The graphics also need to be revamped a lot more frequently than before, perhaps because they rely not so much on good ideas as on quickly outmoded techno logical novelty; perhaps because some sequences are shown more often.

As Peter York suggested, it was to be expected that the 1980s design boom experienced by print graphics and high-street retail outlets would come to TV in the end. But TC did manage to avoid the inevitable for longer than most because commissioning editors had to decide first that they needed design. Although everyone praised the innovations of Channel 4 when the independent network was launched in 1982, its graphics lessons were not really attended to until the government began to redraw the broadcasting map. The pressures placed on long-standing monopolies and the arrival of more new channels, particularly of satellite and cable, have been crucial. Obviously it has meant more programmes to work on. But more importantly, as budgets got tighter, potential market shares shrank and ratings wars loomed, TV chiefs took to thinking that design might be the one thing that would make their shows look better than the other side’s almost identical product and began to view designers as potential saviours.

Hence the rise of channel branding, the most visible example of which is ITV’s 1989 revamp of its on-air image. English Markell Pockett not only had to come up with a new logo which could incorporate fifteen regional variations into a single corporate image to counter the strong national images of new satellite stations like BSB. They also had to create alternative thematic versions of the station ident which would convince an audience that associates “quality” with the BBC of the wealth of good ITV shows. The project was not simply about good graphics, but part of a propaganda battle with the British government.

A critic might suggest that if ITV really wanted to convince viewers that it was a producer of quality shows, it should have spent its money on making programmes rather than on flashy high-tech blips. Perhaps. But conceptions of television have changed radically in the 1980s. in a way, people have caught up with the left-wing academic, Raymond Williams, who observed fifteen years ago that the medium was essentially a flow of images rather than a set of discrete units. The image-stream of English Markell Pockett’s ident for ITV is perhaps the perfect symbol of this.

Today it seems that television is no longer just about programmes, but programming; not shows but schedules. And design, in the form of idents and previews, has become the visual glue which holds schedules together. Hence spending hundreds of thousands of pounds on a thirty-second trailer for a season’s programming is much easier to justify. Especially if the resulting piece of eye candy keeps viewers raised on the short-term stimulation of ads and pop promos from changing the channel.

But has the arrival of design on screens improved the TV we watch? Are we living through an age of televisual dressing or a graphic renaissance, a golden age for TV design? It is a difficult question to answer. Certainly observers from outside Britain have great respect for British TV graphics, and if you compare the clever, technologically complex, ideas-filled, often challenging work produced by the best designers in Britain with the flying logos that still predominate in other European countries, it is easy to agree. Unsurprisingly this has led design companies to think that they can avoid increatins market saturation by setting their sights on foreign screens. In the 1990s it seems likely that some of them will repeat the international success of British advertising agencies.

But before complacency sets in and the British assure themselves that while they may not have the best TV in the world, they definitely have the best TV graphics, we should perhaps ask whether all that invention and technological facility works for the programmes it is supposed to serve. Titles, like ads, may sometimes be better than the programmes themselves. But is that good design?

Take the computer-animated titles produced by matt Forrest for Channel 4’s ill-fated 1988 adult pop show, Wired. Long after the show was discontinued, the titles featuring the specially created “Mad Bastard” character and a host of bopping digital stick men continue to puck up awards at European animation festivals. Justifiably it would seem – the idea was strong, the execution skilful and the package had real impact. So much so that it left the lacklustre show looking even more of an anti-climax. Matt Forrest’s titles didn’t introduce Wired – they blew it off the screen. They definitely weren’t window integrated “good design”.

Perhaps Matt Forrest should have been asked to contribute more to the programme. And in fact this is beginning to happen. Instead of being asked in after a show is completed, designers are now becoming involved at the start of the production process. It makes sense and the results so far, particularly the work done by Baxter Hobbins Sides for Channel 4’s Hard news and McCallum Kennedy D’Auria’s production styling for BBC’s Washes Whiter are impressive. Undoubtedly it is the start of a more general trend. Some designers even have ambitions to move into producing their own programmes.

One example of what these might look like is provided by the work of Diverse’s designer Steve Billinger. In his BBC2 series, Uncertainties and Small Objects of Desire, the technology and effects usually reserved for titles and previews spill over into the main part of the programme. The result is a series of seductively busy, occasionally avant-garde essays in video graphics which deal with ideas without resorting to the visual boredom of the talking head. This is only one way in which graphics might develop. Other designers simply want to make better conventional programmes than the ones for which they currently provide titles.

One effect of involving designers earlier might be to cure them of a tendency to decorative excess, the televisual equivalent of post-modern facadism in architecture. When designers are brought in to provide thirty seconds of tack-on titles, there is a tendency to try to prove their worth (and justify their fees) by doing too much. Perhaps it is significant that companies like McCallum Kennedy D’Auria and Baxter Hobbins Sides are now talking about the advent of an “elegant minimalism”.

Of course it could just be another fad. Like everything else, TV design is driven by the logic of fashion. New trends can be determined by new technology – the reason for the plethora in the mid-1980s of shiny computer-generated bricks in space and flying chrome logos. Or they can be borrowed from the world of art and culture. The popularity of the model animation of Jan Svankmayer and the Brothers Quay led to a spate of rickety baroque titles. Similarly, the use of textured, blow-up super-8 by film-makers such as Derek Jarman influenced TV designers almost as much as it did ad agencies. Indeed, TV designers are continually under pressure to come up with “new” ideas, so they are inevitably forced to indulge in post-modern plagiarism.

The current espousal by designers of minimalism and understatement, the strong single idea rather than fast edits and multiple overlays, live action rather than computer animation, film and natural textures rather than primary colours and video effects, and of a more subtle use of new technology, might just be the latest fashion, the inevitable reaction to five years of technologically generated hyperactive flash. On the other hand, it might also signal the development of a new maturity, a sign that after the appearance of design on our screens, good design, something more desirable but less easy to achieve, may be about to follow.

First published in Eye no. 1 vol. 1, 1990

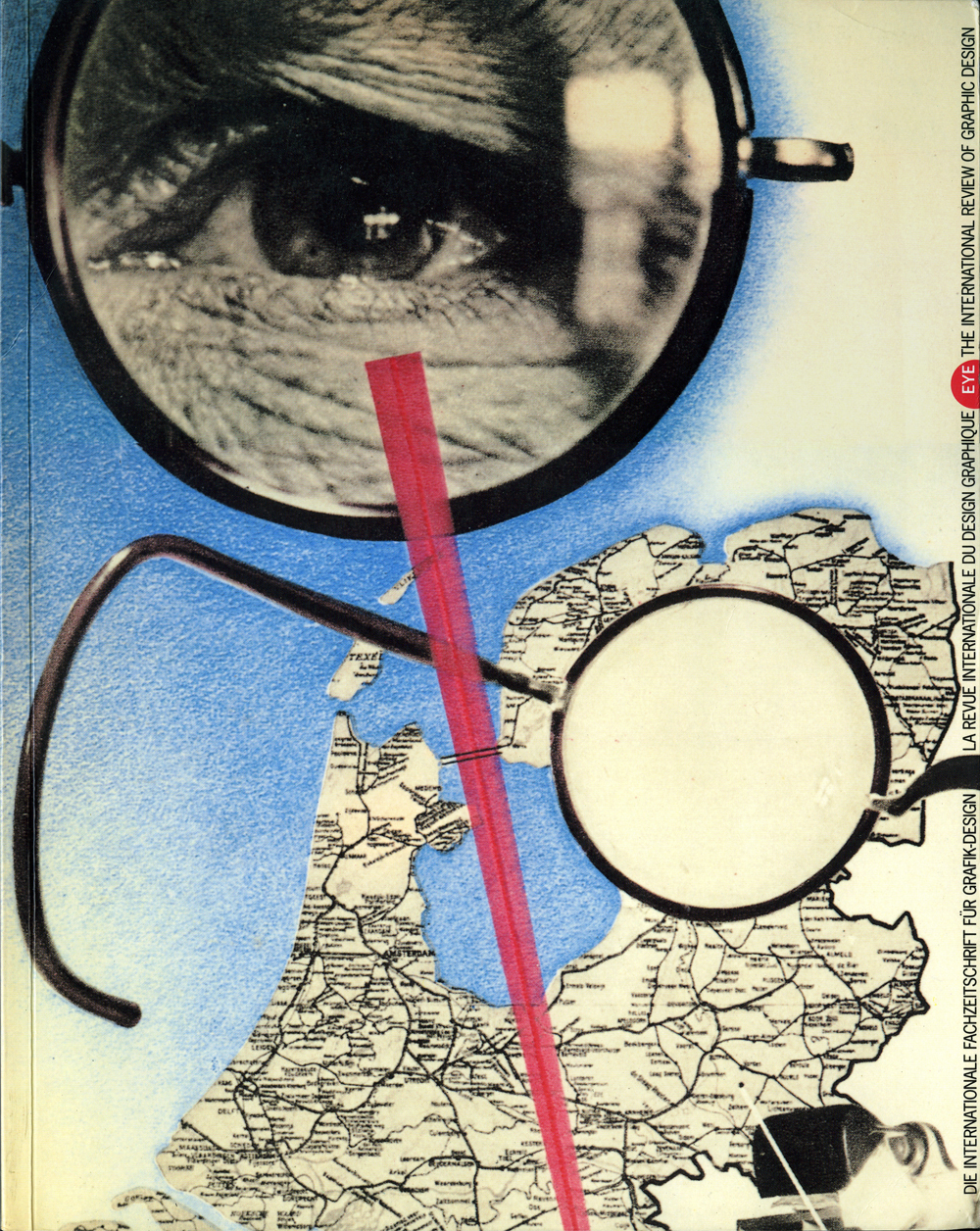

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.