Autumn 2012

An outlandish everyman

These short films throw new light on the eccentric collaboration between 1960s film-maker / designer John Sewell and artist Bruce Lacey. Critique by Rick Poynor

Unless you happen to be interested in the history of British performance art, it would be easy to overlook the recent appearance, on the DVD The Lacey Rituals, of a previously unavailable film written and directed in 1960 by the graphic designer John Sewell, who is something of a lost figure. I learned about the nineteen-minute short, Everybody’s Nobody, from Sewell’s friend and collaborator Bruce Lacey, while undertaking research for my ‘Communicate’ exhibition at the Barbican Art Gallery in 2004. I included Everybody’s Nobody on a monitor in ‘Communicate’, and for me it was one of the show’s highlights (though I have sometimes wondered how many people put on the headphones and watched it all). The short was also illustrated in the book.

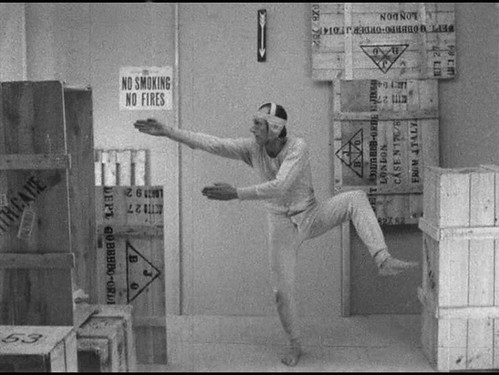

Shot in black and white on 16mm, Everybody’s Nobody is a spoof promotional film for a product called the Mobile Absurd Nonentity (MAN). ‘It’s a sort of synchronised, pressurised, energised, moisturised moron,’ explains the narrator, voiced by Sewell with professional flair. Lacey, a performer with rubber features and a gift for physical slapstick, plays the MAN, clad in grubby long johns and a protective head cap, as a kind of extended music-hall turn. The film’s style of satirical humour with a bleak, apocalyptic edge – these were the years of the Aldermaston marches and ‘Ban the Bomb’ – derives from Goon Show comedy and points to the later absurdist, anti-establishment lampoons of Richard Lester’s film The Bed Sitting Room (1969) and Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

The Mobile Absurd Nonentity (MAN) displays his capabilities and finds a mate.

Top: the opening sequence of Everybody’s Nobody (1960) directed by John Sewell. The MAN, played by Bruce Lacey, emerges from the crate.

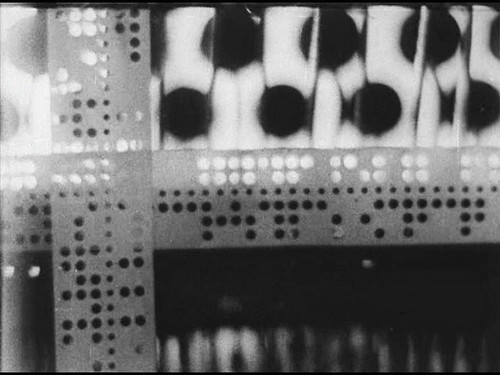

The film’s visual design is fundamental to its impact. Sewell uses a static camera and composes his spare images with draftsman-like precision within the frame. Everybody’s Nobody is at its most obviously graphic in its opening minutes, with near abstract shots of moving computer punched tape (the first image is a man’s head bound with it), an office typewriter in use, and wooden crates covered with arrows, symbols, numbers, stickers and stencilled letters; Sewell allows each letter of MAN to fill the screen. Once Lacey is out of his crate, he begins a series of outlandish demonstrations of the uses of parts of his body – pouring water into his ear, modelling a succession of conspicuously false noses – often viewed in extreme close-up against a plain grey wall.

In the second half, the art direction and set-ups become more elaborate as Sewell reads testimonials in the voices of a nerdy amateur inventor and a ‘satisfied member of the peerage’. The all-purpose MAN turns into a perpetual-motion machine and then a butler. ‘By means of punch tape we formulate him according to your requirements,’ says the narrator. ‘When he has digested his instructions thoroughly he receives his diploma.’ The MAN is clearly no more than an ordinary human being programmed to conform and behave like a robot. The ensuing demonstration of the efficiency of the standard, bowler-wearing office nobody, MAN no. 618, confirms that the manufacturers are in the business of ‘selling people’. No order is too large: they have provided the product for many wars. The MAN will last a lifetime ‘subject to the usual radioactive contamination clause’.

From Everybody’s Nobody (1960) directed by John Sewell.

Sewell and Lacey both studied at Hornsey School of Art and the Royal College of Art, and the British Film Institute’s new DVD set includes two other films directed by Sewell, with Lacey as a performer, Head in Shadow (1951) and Agib and Agab (1953). Seen together, the three shorts suggest that Sewell, who died in 1981 in his mid-50s, was a promisingly original film-maker. He joined the BBC in 1954 to found a graphic arts section and later specialised in designing for book shops and publishers.

In Head in Shadow, the more rewarding of the two rediscovered films, Lacey plays a blind man wandering the streets of postwar Islington trying to find out who dropped a package wrapped in newspaper that he picks up from the gutter. The pace is absorbingly slow, the bomb-damaged locations eerily atmospheric, and Sewell’s hand-held camera dwells on the texture of walls and paving stones, breaking off to admire graphic street posters for Polos, Robinson’s Groats and other goods. The film’s original soundtrack was lost, and in 2003 Lacey added a superbly fitting, trance-like ambient score, ‘Slow Music’ by Morgan Fisher and the late Lol Coxhill.

As the BFI’s DVD booklet suggests, Head in Shadow is best viewed as an artist film, with an existential focus and concentration on mood that is quite different from the concerns of plot-driven narrative cinema. The Sewell films (just over an hour in total) comprise only a small fraction of this excellent two-disc release, which has many other films by Lacey – defiantly eccentric and unclassifiable, and a significant figure on the 1960s art and performance scene.

The Lacey Rituals: Films by Bruce Lacey (and friends), BFI, two DVDs.

First published in Eye no. 84 vol. 21, 2012

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 84 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.