Monday, 6:00am

14 March 2016

Depth and ambiguity

Another Way of Telling, by John Berger and Jean Mohr, extends the possibilities of the photographic narrative. Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for eyemagazine.com.

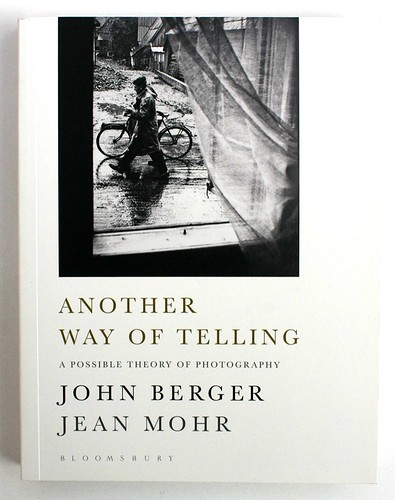

Another Way of Telling, published by Writers and Readers in 1982, was the fourth collaboration between the critic John Berger and his friend Jean Mohr, a Swiss photographer. Granta republished it in 1989 but it has been unavailable for many years, although Berger’s Penguin collection Understanding a Photograph (2013) found room for two key texts. Bloomsbury’s new edition, aided by some significant visual enhancements, reintroduces a critical inquiry of considerable originality and this is the best version published to date.

This time the book has acquired a subtitle, ‘A Possible Theory of Photography’, a phrase the authors use in the preface. Their aim, they write, was to make a book of photographs about the lives of mountain peasants – since the early 1970s, Berger has lived in a small alpine village in Haute-Savoie in the east of France. For seven years, the villagers were Berger and Mohr’s collaborators and Another Way of Telling is ‘in the most profound sense their life’s work.’ The book is also about the nature of photography, what photographs mean and how they can be used.

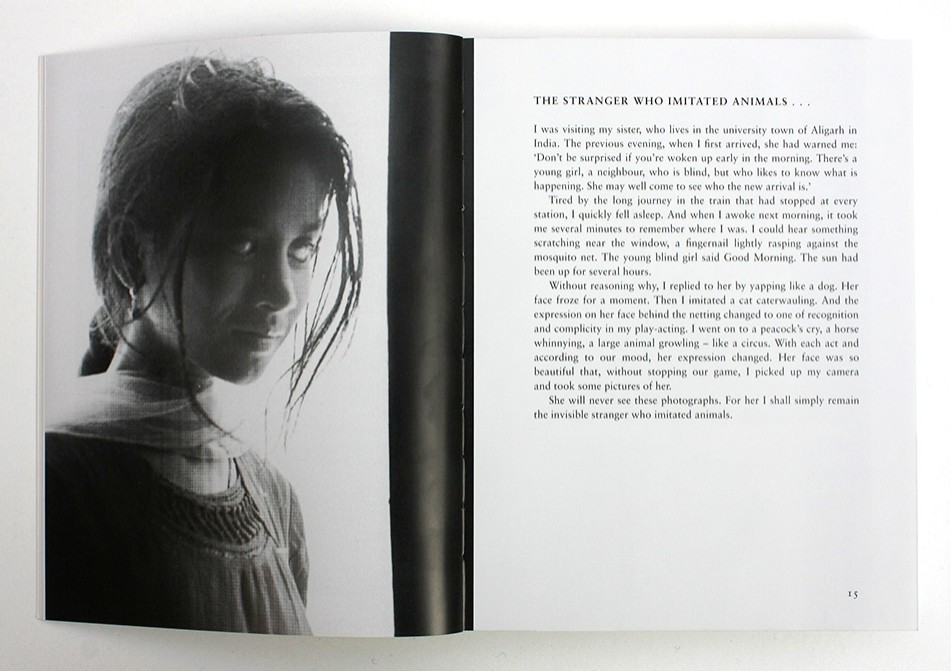

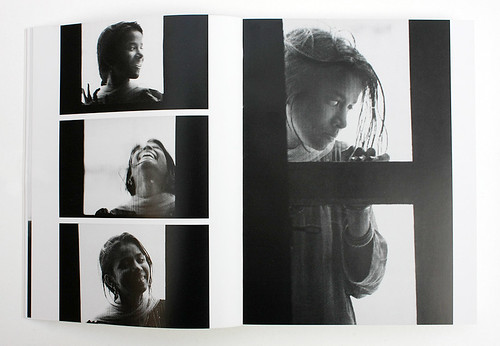

Right and top: Aligarh, India, 1968. All photographs by Jean Mohr unless otherwise stated.

Berger and Mohr’s earlier projects had benefited from exceptionally sensitive design by Gerald Cinamon (A Fortunate Man and Art and Revolution) and Richard Hollis (A Seventh Man). Another Way of Telling had no credited designer, despite its extensive visual content, and the layouts did not serve the photographs well. The margins around the pictures were too small in many cases and the images often felt over-scaled for their pages. With the same lack of nuance, many photos were enclosed by a heavy box rule, although this was not implemented throughout with any consistency. While the reproduction in the first two editions was adequate for books that were only low-cost paperbacks, the mid-tones were flattened with some loss of detail.

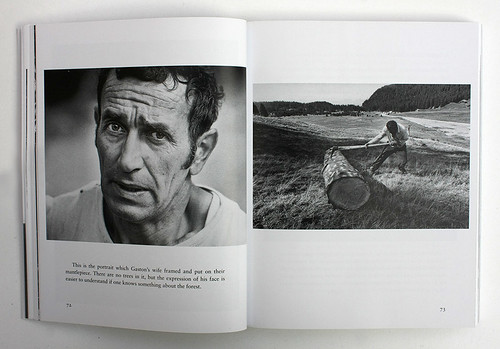

Roche-Pallud, the Sommand Plateau, 1978.

The page width is reduced in the new edition, becoming less square, but the flow of photographs is more satisfying because they have been resized where necessary to give slightly bigger margins. This extra white space provides a visual cohesion and tautness that was previously missing and these (still uncredited) improvements are felt most keenly in a photographic narrative by the authors titled ‘If each time …’ consisting of around 150 images mainly by Mohr presented without support of any text. The reproduction is sharper, too, and Mohr’s highly empathetic photographs of country life are greatly enhanced by the tonal delicacy now revealed. As with the 2015 reissue of A Fortunate Man, there are a number of instances where new images of the same subject are substituted and other cases where pictures are cropped differently. There is no note to explain these changes. However, unlike with A Fortunate Man, the picture relationships established in the original layout have not been tampered with.

Sommand, 1978.

Sommand, 1978.

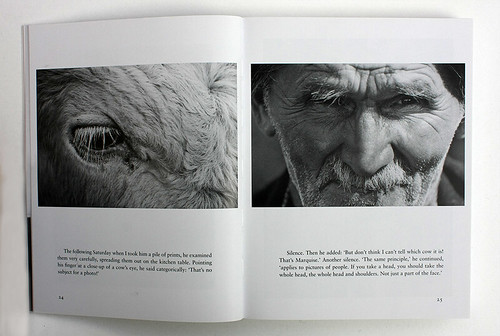

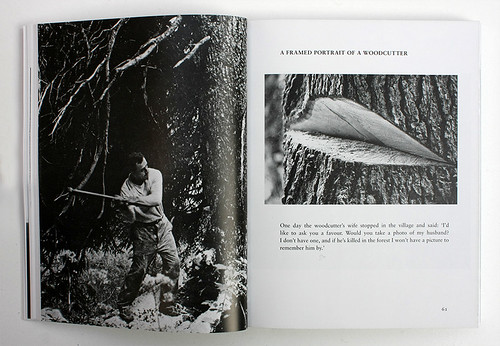

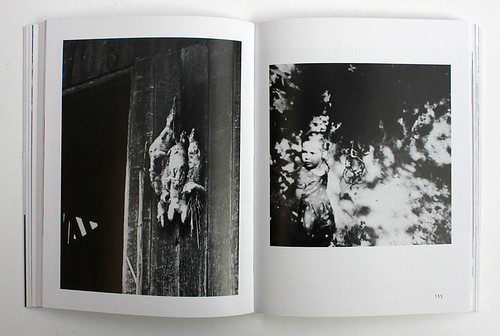

The five-part structure of Another Way of Telling has a seductive informality, allowing Berger and Mohr to provide both individual and joint contributions. In ‘Beyond my camera’, the opening chapter, Mohr intersperses photographic stories about an elderly peasant and a woodcutter with experiences from elsewhere in the world – a blind girl he met in India, poor children running along next to a train in Djakarta. In the essay’s most pointed section he asks nine people from different walks of life to interpret what they see in five of his pictures, such as a child clasping a doll and a man standing in a tree, and receives highly divergent responses, anticipating a point central to Berger’s investigations in ‘Appearances’, the next chapter: ‘All photographed events are ambiguous, except to those whose personal relation to the event is such that their own lives supply the missing continuity.’

This section is the theoretical heart of the book and it is written in Berger’s characteristic manner: short sentences and paragraphs dense with thought that come to seem almost oracular in the certainty of their rhythm. It isn’t especially easy reading – one often pauses to ask whether an assertion is true – but it is highly rewarding. Berger has a rare ability as a critic to connect with what fundamentally matters and to translate his feelings and intuitions looking at an image into deeply humane insights. See, for instance, his subtle reading of a photograph by André Kertesz of a red hussar leaving his wife and child, in Budapest in 1919, to defend the new Hungarian republic.

Almost everything in the book can be understood as preparation for what Berger and Mohr attempt in ‘If each time …’, a 140-page experiment in communication using a sequence of photographs. This is not the factual, eyewitness account of real events familiar from photo-reportage. The old woman reflecting on her life – on work, love, death, pleasure, solitude and the village – is an invented person, like a character in a story, except there is no story, only the loose suggestion of a narrative, which the reader is free to interpret. Berger and Mohr stress there is no single ‘correct’ reading. As Berger demonstrates with a series of diagrams, in a printed photographic sequence (unlike in a film) the ‘montage of attractions’, as the film-maker Eisenstein termed it, operates in both directions and the viewer can wander at will through the images.

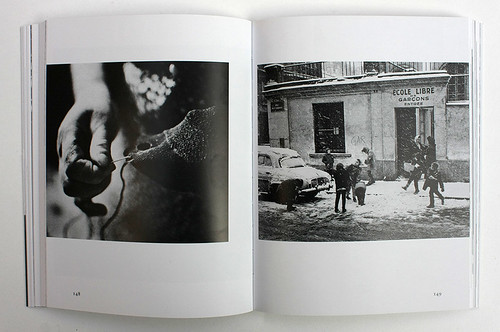

A four-spread sequence from the photo-narrative ‘If each time …’. J.’s hands (left) and Paris (right).

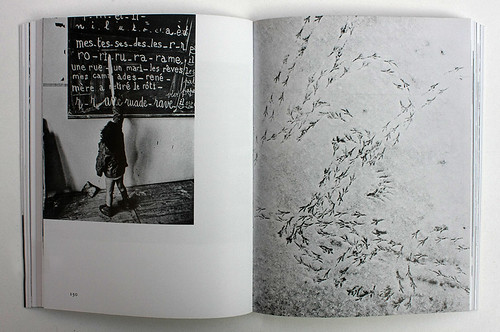

Tunisia (left) and bird tracks, Geneva (right).

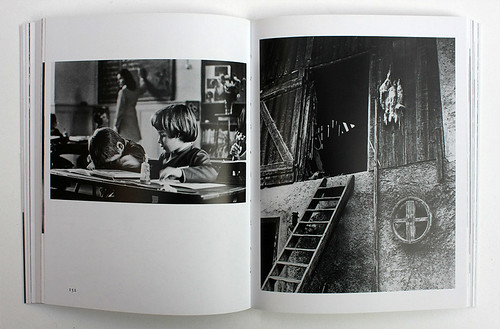

School in the township of Mieussy (left) and rabbit skeletons, Haute-Savoie (right).

Rabbit skeletons, Haute-Savoie (left) and Katya (photo: John Berger).

More than 30 years after its first appearance, ‘If each time …’ remains as challenging as it was prescient and perhaps its moment has come. There is now an international audience for highly associative photobooks (such as Redheaded Peckerwood, reviewed here) in which the viewer is encouraged to make personal connections between discontinuous images. The tidying up of Another Way of Telling’s pages allows us to focus on the sequence as a visual construction without the distraction of its former messiness. The subject matter may seem distant to some, although millions around the world still lead similar lives of harsh subsistence, but the implications for the photographic page are boundless.

Cover of Another Way of Telling by John Berger and Jean Mohr (Bloomsbury, 2016) with a photograph by Mohr taken in Poland. Cover design: Holly Ovenden.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, London

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.