Spring 2009

Is type design teaching losing its soul?

Formulaic, modular approaches threaten the chemistry of the master-apprentice model.

The current era of type design and typography recalls that famous phrase that is often quoted as being an ancient Chinese curse (but probably isn’t): ‘May you live in interesting times’.

There are several things that make the present time typographically interesting. On a technical level, there are two standards with unprecedented power: Unicode and OpenType. Unicode is like a worldwide alphabet that ideally gives every character used in every language its own official little spot in the typographic universe. OpenType is the coding format that makes it possible to accommodate a specific design of all these signs into one digital font. An OpenType font has thousands of possible ‘positions’, empty boxes each of which can contain a character for any writing system – like Arabic or Inuktitut or Khmer – as well as typographic frills such as unusual ligatures, ampersands, or six ways to write numbers. OpenType has been around for a decade, but only in the past three years or so has it become the de facto standard for new typefaces, giving young, flexible type foundries a head start and the existing ones a headache, and a lot of conversion work to do.

Technological progress also enables savvy designers to produce large families of typefaces without drawing each character separately. It is possible to generate entire fonts by letting the computer interpolate two existing designs (say, an extra bold and a light weight of a typeface) and calculate intermediate fonts, which, if the original designs are carefully drawn, require only minimal correction. These and other ways to automate the design process have spawned a new phenomenon – the ‘superfamily’. Text families that come in two to five widths, each in seven or eight weights, with seriffed and sans-serif varieties, are not an exception any more.

From the user’s point of view, living in interesting times is a mixed blessing. Type design has become a geeky activity, and geeks do not always have a great understanding of how non-geeks function. When no one stops them, geeks tend to assume that user-friendliness equals adding more options. Video recorders, mobile phones, even cars, come with loads of functions hidden behind introverted interfaces. And now typefaces do, too.

There used to be separate fonts for such niceties as small caps, medieval figures or scientific notation systems. All of this is now in one font. But both the type manufacturers and the designers of layout programs have yet to conceive an unequivocal signage system to show users what is where in the typographic forest, and whether it is there at all.

Don’t get me wrong: for those who enjoy exploring the ins and outs of OpenType functionality, typography has never been more fun. But for those who are not that interested in the minutiae of fontology (and few graphic designers are also dedicated typesetters), it is becoming frustratingly easy to make mistakes.

Type design, of course, is not just about systems and functionality. It is also about the letterforms themselves: optical subtleties, delightful curves, delicate compromises between legibility and aesthetics. On this level, we’re going through a period of consolidation. The reckless experimentation of the early to mid-1990s has been replaced by thoughtful exploration. While fifteen years ago, every young type designer went through his or her grunge / (de)constructivist phase before embarking on something more serious, students today often start out on a much higher level, conceptually and technically. The quality of debut typefaces is amazing.

Yet here, too, the pitfalls of technical sophistication are manifest. In text type as well as the stunningly popular genre of script fonts, OpenType’s ability to include alternate characters are exploited to the max. An OpenType font can be programmed so that certain letters are replaced by ‘contextually’ more appropriate or interesting varieties, such as fancy ligatures and ornamented letters. Type designers seem to feel obliged to load their fonts with outrageous and ultimately unnecessary goodies, just because they can. Technological progress is provoking a kind of mannerist phase in type design: a new wave of kitsch.

Type’s popularity

In complex periods of transition like the current one, schools find themselves to have shifting and multiple responsibilities. The current – possibly unprecedented – high level in type design is partially due to the fact that type design is being taught at all. The master’s degrees in Reading and The Hague have helped set standards and create a ‘school’ of type design that is European in character but, with graduates working and teaching in the former Soviet Union, Latin America, East Asia and the Middle East, global in impact. In their approach, both departments have to a large extent remained true the old studio system based on the master-apprentice relationship. With mentors such as Gerard Unger and Fiona Ross in Reading and Gerrit Noordzij’s students in The Hague, both schools offer an education rooted in traditional values but informed by decades of cutting-edge praxis.

Yet many students will never get to Reading, The Hague or one of the few other places that offer a specialised MA curriculum, and want to learn about type as part of their graphic design education. Type design has become a popular subject. Why is that? I have two theories. 1. Designing fonts is a way to single-handedly make a real product, which can be shared over the internet or even sold through easily accessible channels such as MyFonts. 2. On a more subliminal level, students might be a bit anxious or confused about the ‘everything-is-possible’ aspect of their craft. They want constraints, and type design offers plenty.

As a result many schools are adding type design courses or workshops to their curriculum. They may find it hard to determine, though, what is the best way to teach this highly specialised craft. Faced with the dilemmas of the digital age, many design colleges have opted to produce raw material: graduates who can produce interesting concepts and make great photocopies, but don’t have a clue about printing techniques and have never learned how to draw. In the European Community, the tendency to stress thinking over doing is further enhanced by the Bologna reforms, in which an academic curriculum of standardised modular courses is replacing the studio system. In some countries, such as Germany, there has been resistance and even rebellion against what is seen as an attempt to deprive schools of their ‘souls’. Elsewhere, in France for instance, there is little room for discussion, and art schools are being ‘academicised’ against the will of teachers and students, throwing out quite a few babies with the bathwater.

In type design education, a formulaic ‘Bolognese’ approach might simply not provide a viable solution. Although the making of type is not the secret art it was for centuries, it does involve multiple skills and complex knowledge that is best passed on through the chemistry of a master-apprentice situation. To simultaneously impart a set of aesthetic and theoretical principles as well as a sensible mastery of digital techniques, one need teachers with wisdom, talent and up-to-date working experience. In order to attract such teachers, schools need to create a working environment that is interesting to student and professor alike. Schools that start at the wrong end – limiting teaching to theory and traditional drawing techniques, leaving it to the student to explore the digital tools or, worse, overexposing students to the dazzling possibilities of digital trickery – risk producing what the Germans call ‘dangerous half-knowledge’. It requires a broad and inspired education to produce designers who don’t get lost in technical details but have the right frame of mind to make life easier for everyone – in interesting times.

Jan Middendorp, designer, design writer, Berlin

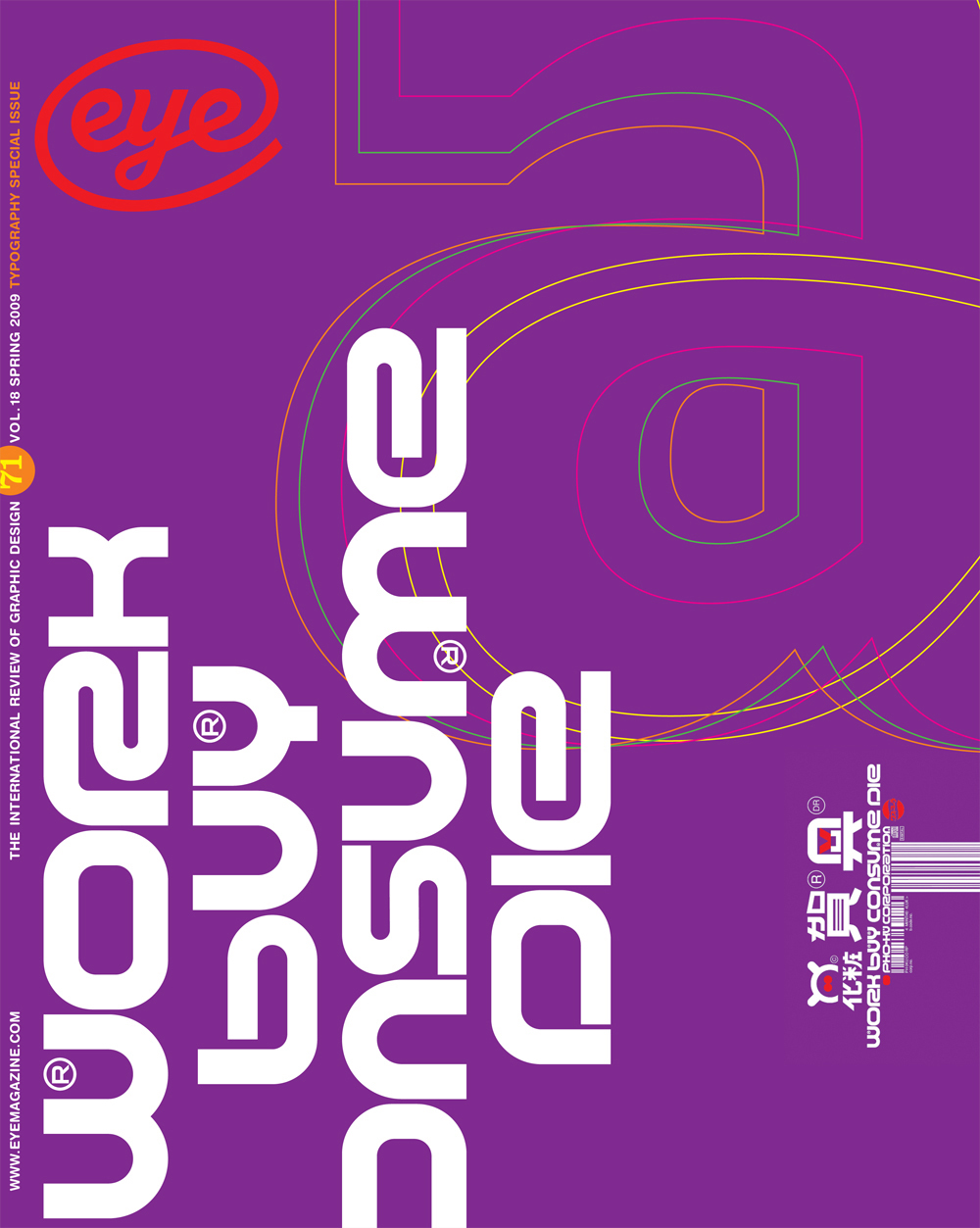

First published in Eye no. 71 vol. 18 2009

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.