Friday, 6:00am

6 June 2014

Photographer as page maker

Walker Evans

David Campany

Design history

Graphic design

Magazines

Photography

Reviews

Visual culture

Web Critique

David Campany’s examination of Walker Evans’ freewheeling magazine work – for Fortune, Architectural Forum, Life, and others – is a revelation. Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for eyemagazine.com.

Walker Evans is one of the most highly regarded photographers of the twentieth century. Yet one side of his work has always been downplayed and overlooked: his work for magazines, most of which has remained unknown.

When these pictures are mentioned – as, for instance, in the monograph Walker Evans: The Hungry Eye – the tone is regretful, conjuring an image of a photographer forced by the dictates of the job to provide images to order. While some of the photographs taken for these assignments may get reproduced, they are not shown as they were organised and printed in their original layouts. Only the most assiduous collector of old magazines could have any conception of how Evans’ photographic stories for Fortune, Architectural Forum and other titles looked on the page.

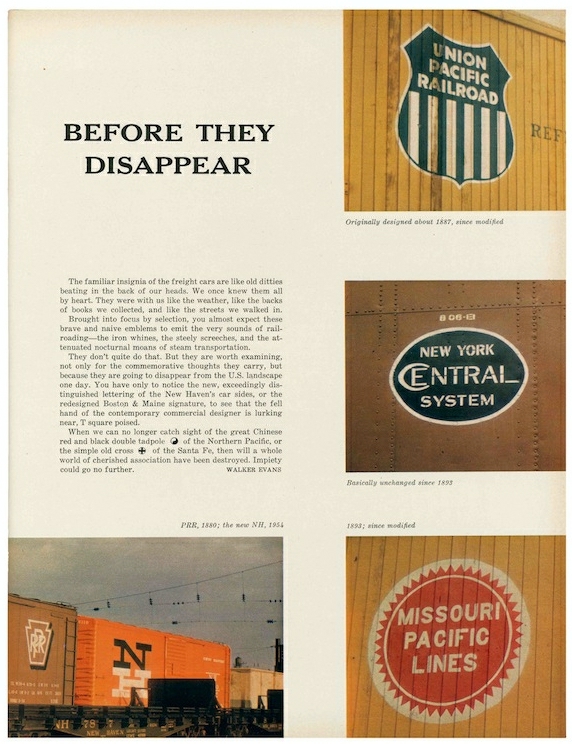

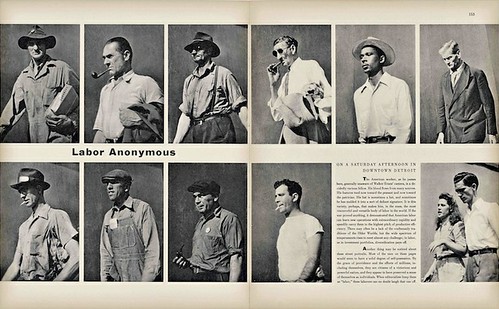

Walker Evans, ‘Labor Anonymous’, Fortune, November 1946. Top: Walker Evans, ‘Before They Disappear’, Fortune, March 1957. Text also by Evans. Both images courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time Life Inc.

Photography writer David Campany’s Walker Evans: the magazine work (Steidl) is consequently a revelation. The book has two principal parts, a long illustrated essay followed by a section of plates where Campany reproduces many of the most significant visual stories in their entirety. They are beautifully printed. If anything is going to prompt a reconsideration of Evans’ engagement with magazines, it will be this meticulously researched and highly readable investigation.

Evans sought an independent position within mainstream culture and he found it at Fortune, one of the most visually outstanding magazines ever published (see Eye no. 2). His association began in 1934 and in 1945 he was appointed as the publication’s only staff photographer; three years later he became ‘special photographic editor’. He reported to the managing editor, bypassing the art directors (Will Burtin, then Leo Lionni), assigned himself projects, and took charge of his own layouts, typography and titles. He held the post for seventeen years. An editorial described him as the ‘most freewheeling’ member of staff. ‘Evans had the best job,’ recalled assistant art director Max Geschwind. He would go off travelling for weeks and Fortune covered his expenses. The idea of him being in thrall to Fortune, not free to do the work he wanted, is inaccurate. Even so, he described Time Inc. as a ‘deadly place’. He seems to have viewed his berth there as what would much later be dubbed a temporary autonomous zone, though it ended up lasting for years.

Walker Evans, ‘The Wreckers’, Fortune, May 1951. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time Life Inc.

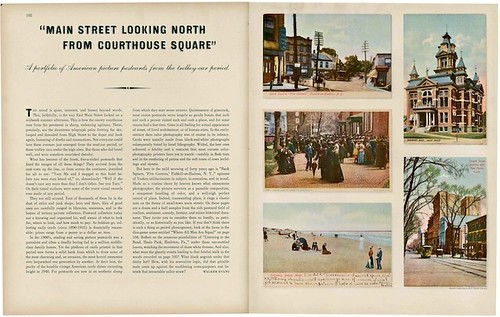

Walker Evans, ‘Main Street Looking North from Courthouse Square’, Fortune, May 1948. Text also by Evans. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time Life Inc.

Nor did Evans meekly fall into line with the conventions of magazine journalism. Campany shows that he actively worked against them: ‘His pieces for Fortune had no beginnings, middles or conclusions. Each contemplates a small cluster of related themes, refusing speed at every turn, to remain open-ended.’ He argues that most of Evans’ photo-stories were ‘quiet ripostes’ to what was going on elsewhere in this lavish publication intended for economists and business leaders. Specialists in photography who sideline Evans’ magazine work have failed to notice that his critical perspective and reflexivity was ahead of its time. His concerns anticipated Conceptual Art, though its proponents would largely ignore his work.

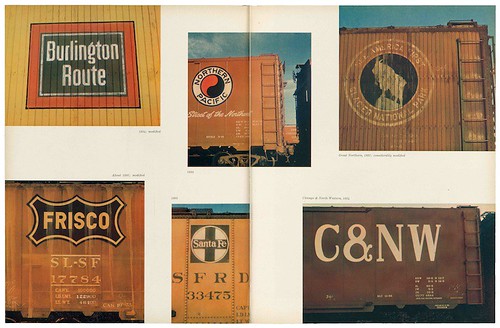

Walker Evans, ‘Before They Disappear’, Fortune, March 1957. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time Life Inc.

A good example is the feature ‘Labor Anonymous’, published in Fortune in November 1946, which displays pictures of walking workers, taken against a featureless wall, on a Saturday afternoon in Detroit. Campany shows how its meaning is constructed through visual editing. The images are portrait-shaped crops from bigger pictures. Evans tended to shoot wide, expecting to adjust the picture later; he liked images of different proportions on the page. He has placed the only person who turns to look at the camera in the leading position on the layout, to thwart the ‘ethnographic fantasy’ of unsuspected observation, suggests Campany. The man’s eyes remain hidden and unknowable in shadow. With his ironic headline and sceptical text, Evans challenges the lazy assumption – in an issue devoted to ‘Labor in U.S. Industry’ – that these people are ‘types’ who can easily be deciphered. The visual essay becomes a meditation on how to read a photograph and this complexity will be lost once the pictures are detached from their allotted positions in the layout and presented as a collection of street portraits, as some of them are, for instance, in Walker Evans: The Hungry Eye.

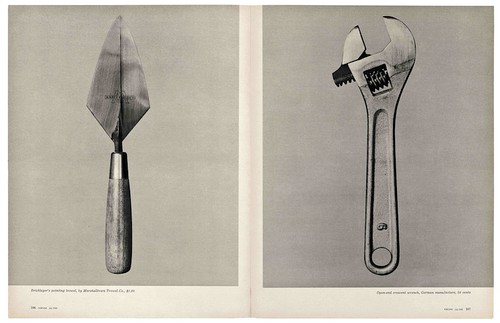

Walker Evans, ‘Beauties of the Common Tool’, Fortune, July 1955. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time Life Inc.

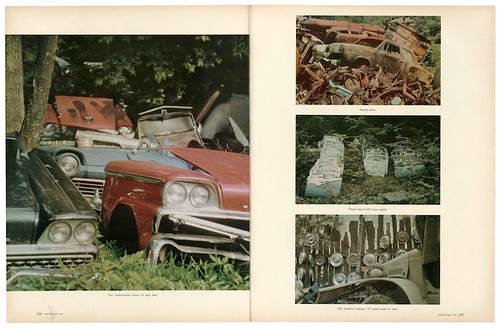

The range of Evans’ magazine work is hugely impressive and now it has been gathered together it seems all the stranger that curatorial oversight led to its neglect. In a way that is again still contemporary, Evans made no rigid distinction between found images and high art – several stories were based on postcards from his own collection of thousands. He was fascinated and sometimes dismayed by the changes that sleek modern design had wrought. He photographed railroad freight-car insignia, knowing they would soon disappear, and in a story for Life, presented America’s doomed architectural heritage. He documented everyday hand tools, vintage office furniture, old industrial buildings and warehouses, small-town railroad stations, sidewalk retail displays (‘Does this nation overproduce?’ he asks), auto junkyards, and ‘the restless, cacophonic design created by time, the weather, neglect, and the fine hand of deliquent youth.’ His first ambition was to write and he often composed his own introductions.

Walker Evans, ‘The Auto Junkyard’, Fortune, April 1962. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time Life Inc.

Campany’s unmissable study is another sign that perceptions of photographic history are undergoing a necessary shift. The centrality of the photobook, demonstrated by the campaigning of Martin Parr and others, is causing museums to reconsider how to show these printed works. The paradoxical position of magazines is that they are cardinal to culture, deeply inscribed with meaning, yet disposable and rapidly replaced. Even Campany suggests that it might not be possible for ‘posterity to rest upon such things’, despite his wry observation that MoMA’s Evans retrospective in 1971 sidestepped his use of the printed page as a ‘primary site’, a place of experimentation and cultural questioning, concentrating instead on the single exemplary picture. Yet a view of photographic history that continues to privilege the artist’s free expression over the medium’s other fertile possibilities is much too limiting. We need a more nuanced understanding of how photographic meanings are mediated by design, and Evans possessed this. He was able to think as both a photographic artist and a designer. After leaving Fortune in 1965, he became Professor of Graphic Design at Yale University.

David Campany, Walker Evans: the magazine work, Steidl, €48

Walker Evans, ‘Color Accidents’, Architectural Forum, January 1958.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, London

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.