Tuesday, 12:00am

31 August 2010

Survivor

Graphic designer Romek Marber bears witness to one of the great crimes of the past century. Critique by Rick Poynor

Web-only Critique written by Rick Poynor exclusively for eyemagazine.com.

A few years ago, visiting Romek Marber, inventor of Penguin’s 1960s cover grid, he showed me a document he had written telling the story of his experiences during the Second World War. Marber, born in 1925, is a Polish Jew and a Holocaust survivor. Until that moment I had no idea what he had gone through. I wanted to read his text – I caught brief glimpses of photographs of his family – but I had only just met him. He didn’t ask me if I would like to read it and I felt it would be intrusive to suggest this, though I now think he wanted me to. I have wondered about Marber’s story ever since.

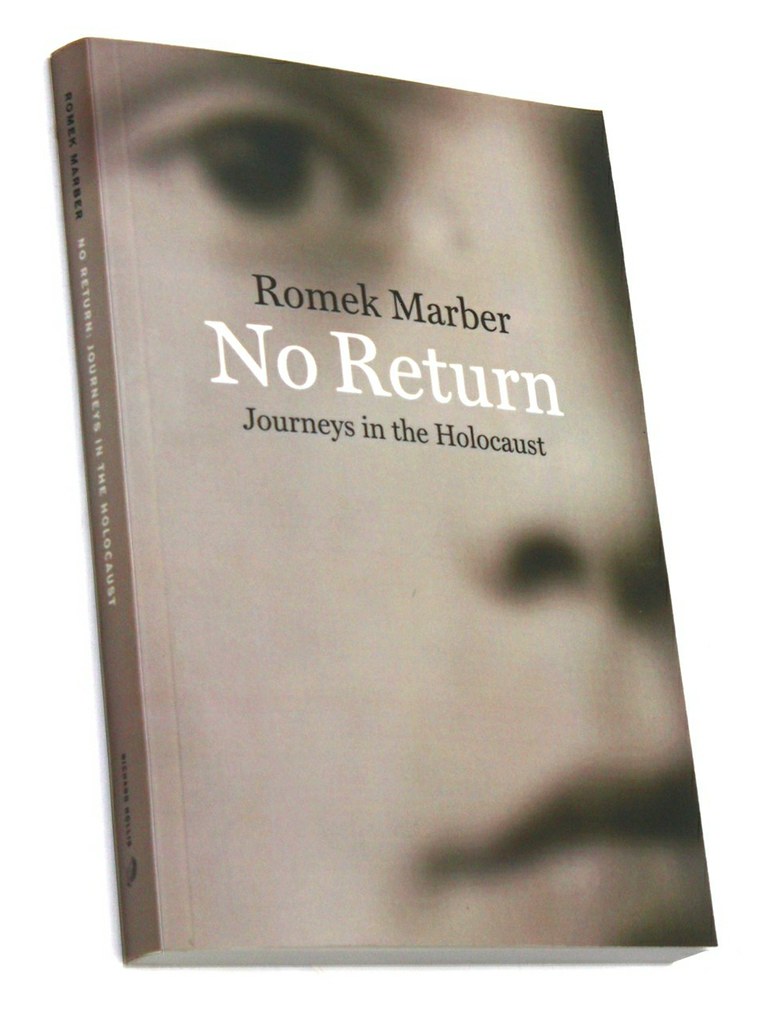

Six years later, No Return: Journeys in the Holocaust, a book by Marber based on the text he showed me, arrived unexpectedly in the post. He had sent it himself. No Return is published by Richard Hollis under his own imprint, in association with Five Leaves Publications in Nottingham, and is the first of Hollis’s new titles to appear.

Hollis, too, had been unaware of Marber’s past. He hadn’t seen him for many years when he bumped into him, in 2006, at the opening of the Alan Fletcher exhibition at the Design Museum. Marber said he had been visiting the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington in connection with pictures of family members murdered by the Nazis. He mentioned his text, Hollis asked if he could read it and Marber sent it to him.

Appearing 65 years after the events it describes, Marber’s quietly devastating narrative was written with reluctance in 1998, in his early 70s, after he was urged to commit his memories to paper. Survivors were often reluctant to talk about their terrible experiences in the early years after liberation, but most of the famous accounts – Elie Wiesel’s Night, Primo Levi’s If This Is a Man, Wieslaw Kielar’s Anus Mundi – were still published decades ago.

Marber’s powers of recall for even the smallest details are acute. On the few occasions he can’t retrieve a name, or remember whether some shower water was hot or cold, he is careful to say so. He notes with regret that he has forgotten the number he was given in the Plaszow concentration and slave labour camp near Krakow, where he was incarcerated from September 1943 to January 1945.

Plaszow might sound familiar. This was the hellhole re-created in Steven Spielberg’s film Schindler’s List (based on Thomas Keneally’s novel), where the sadistic SS commandant, Amon Göth, takes pot shots at prisoners with his rifle, before breakfast, from the balcony of his villa overlooking the camp.

In Plaszow, Marber had the ‘luck’ to be classified as a skilled worker. The days were long and punishing but he could work inside rather than breaking his back outside in dreadful weather, toiling in thin rags. He saw many acts of viciousness and murder and describes passing perilously close to Göth and his henchmen standing near bleeding bodies, among them people he recognised. He doesn’t dwell on these atrocities, though, or embellish them, or say much about his feelings. Images such as the hanging boy who Marber is forced to march past, along with the boy’s sister and the other prisoners, tell us all we need to know about the daily struggle to survive in this depraved regime of cruelty.

As the war entered its final stages, the Nazis began to close camps and eradicate the evidence of their crimes. Thousands more met their end on death marches. Marber passed through Auschwitz briefly – the crematoria had been destroyed by then and the Russians were closing in – and he was transported by train in a freezing open wagon to the Flossenbürg camp. ‘The dead multiplied each day and the corpses were removed at each stop.’

At Flossenbürg, they were compelled to sleep in shifts, so overcrowded was their barracks, while everyone else squatted on the floor jammed together in strict rows for hours on end. About to be deloused in an icy shower, Marber leapt on to a table, kicked an orderly in the head, ran away and managed to join his uncle Abek and other prisoners on a train bound for the Plattling camp in Bavaria.

Here, conditions were even filthier. After collapsing on a work patrol and sleeping for many hours, he awoke to find the camp empty. He crawled through the barbed wire to his freedom. The war was over.

Later, in Italy, his final piece of good fortune came when the British MP Tom Driberg, hearing that he couldn’t obtain an entry permit because he was over eighteen, arranged for Marber to enter Britain in 1946. Both his father and brother had escaped the Nazis, eventually arriving in the country. His mother and sister died in the Belzec extermination camp and the same fate befell many other family members. Marber writes with great feeling about family life in Turek, the town where he grew up. He shows us with clarity what was expunged.

In 1951, Marber began his graphic design studies at St Martin’s School of Art; he completed them at the RCA. There could be no return to Poland.

Marber is a man of dignity, strength and resilience; he bears witness to the outrages he saw as a teenager without a hint of self-pity. Rebuilding himself after years of unimaginable hardship and horror, design has been an affirmation of life.

No Return: Journeys in the Holocaust by Romek Marber is published by Five Leaves Publications at £7.99

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, London

First published on eyemagazine.com, August 2010.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.