Summer 2012

The woman who took on the Wolf Man

Graphic novel

Sława Harasymowicz’s first foray into graphic novels illuminates a Freudian case history with thrilling clarity. Critique by Rick Poynor

‘The Wolf Man’ is Sigmund Freud’s most famous case study and it has been described as the test case on which the theory and efficacy of psychoanalysis rests. Did Freud’s ‘talking cure’ really make his patient better?

The Viennese father of psychoanalysis, who published his text in 1918 with the title ‘From the History of an Infantile Neurosis’, claimed that it did. But the Wolf Man himself, Sergei Pankejeff, an impoverished Russian aristocrat whose sister and father committed suicide, denied that he was ever cured and remained troubled to the end of his life.

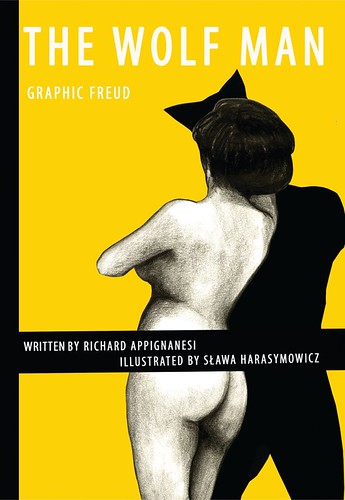

This tale of melancholia and dysfunction might not sound too promising for a graphic novel, but SelfMadeHero is proving to be a publisher with a flair for unlikely subjects. Previous publications have included graphic biographies of Fidel Castro, Hunter S. Thompson and Kiki de Montparnasse (see Eye no. 79 vol. 20), and The Wolf Man is the first in a proposed ‘Graphic Freud’ series based on the psychologist’s most famous case studies. Richard Appignanesi, its writer, is founder of Icon Books and a master of the graphic translation of complex cultural ideas. His books include graphic introductions to Freud, existentialism and postmodernism, and he has adapted fourteen of Shakespeare’s plays for SelfMadeHero.

The Wolf Man is Polish illustrator Sława Harasymowicz’s first graphic novel, and she is an inspired choice of artist for the project. Harasymowicz graduated in 2006 from the Royal College of Art, where she studied with Andrzej Klimowski, who has created several books with SelfMadeHero. In 2009, she was a double winner at the V&A Illustration Awards with work for Penguin Books and the Guardian; in the previous year she was awarded an Arts Foundation Fellowship.

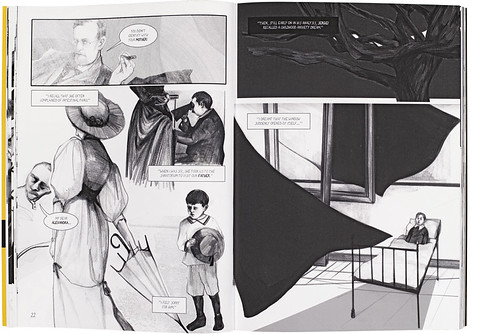

Spread depicting the Wolf Man’s boyhood dream of the white wolves.

Harasymowicz’s style is highly unusual for the medium. Where conventional comic book art is first pencilled and then inked for maximum clarity and impact, she draws most of the image in pencil, carving out her formally clothed figures, often lost in thought, with an emphatic line and vigorous shading. Her drawings are passionate, emotional and fiercely committed to the subject matter. There is an energetic looseness and a dream-like lack of finish in details that need only be implied that give her images great expression and vitality. She shows an effortlessly fluid and varied command of page structure, which more experienced graphic novel artists might envy. By cutting up her drawings and moving the parts into position, she achieves dramatic overlaps and transitions. At times the demarcations between panels are so understated that the spread becomes a single layered yet integrated composition.

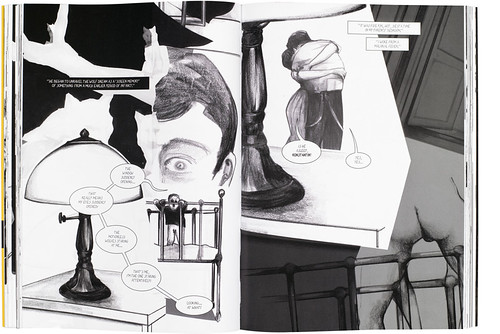

These visual strengths are never more apparent than in the sequence where the Wolf Man recounts to Freud the childhood anxiety dream that gave his case study its name. A window blows open and the young Pankejeff sits up pinned with fear in his bed as black curtains billow above him. In the walnut tree outside, he sees six or seven white wolves staring at him. He gave Freud a scratchy drawing that he made later of the scene and Freud included it in his case study – Harasymowicz assimilates this graphic motif into her pages. Later, Pankejeff tells Freud about a memory of waking in his cot to see his father and mother having intercourse, and Freud suggests that this traumatic discovery returned in disguise in the dream of the wolves.

The story continues after Pankejeff has finished with Freud. Being the famous Wolf Man has become his identity. He is convinced that Freud is responsible for his financial misfortunes, yet in his desperation he boasts: ‘I am Freud’s greatest success.’

The Wolf Man as a child wakes to see his parents having sex.

In partitioned Vienna, the Russian secret police interrogate Pankejeff. He is still unhappy, still wonders about his motivations, and still thinks analysis could help. Other psychoanalysts seek him out. By the end, however, he is telling a journalist that Freudian analysis has been a catastrophe. He died in 1979 at the age of 92.

Appignanesi does an exemplary job of turning Freud’s complicated exposition into succinct and readable speech, though the book is let down, just a little, by a spindly lettering font that feels slightly too small and is poorly matched to Harasymowicz’s muscular drawings.

SelfMadeHero should pay more attention to these design details. Trade printing has its limits, but blacker blacks would have given Harasymowicz’s artwork even greater punch. Her moody graphic style, with pungent traces of Polish poster design, is perfectly suited to mid-twentieth-century subjects and settings, and could be applied to many classic novels and other narratives with psychological, existential and noirish themes. She has the potential to become a significant visual innovator in a graphic medium hardly lacking in talent. This exciting and original book will repay repeated viewing.

Cover of The Wolf Man, written by Richard Appignanesi and illustrated by Sława Harasymowicz, published by SelfMadeHero, 2012.

Rick Poynor, writer, founding editor of Eye, London

First published in Eye no. 83 vol. 21 2012

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 89 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.