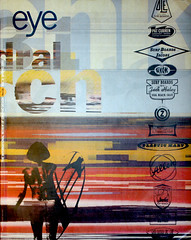

Spring 1995

Encounter with the Netherlands

Dutch Graphic Design: A Century

Amercian Institute of Graphic Arts <br>New York, 21 October - 15 December 1994<br>Chicago Athenaeum, Chicago<br>10 March - 7 May 1995Dutch design is on the move. In the US, in New York and Boston alone, no fewer than five notable exhibitions, on graphics, applied arts and architecture, opened during the final three months of 1994. This recent flurry of activity is part of an international groundswell of renewed interest in twentieth-century Dutch design that surfaced in Europe several years ago and has risen steadily since. The Dutch influence on design, particularly graphic design, is acknowledged without contest. Why, then, this current wave of appreciation?

The past offers a clue. As today’s designers leave one era for the next, they grapple with twenty-first-century technological, formal and ideological challenges not unlike those faced by their European counterparts of the late 1800s. In an equally tentative time, it fell to Dutch architects, painters and typographers to buck historical design conventions ill-suited to burgeoning industrialism and populist consumerism, and chart a new course for what by mid-century would be defined as the profession of graphic design. Moreover, the uniquely Dutch embrace of a variety of artistic, philosophical and spiritual influences, from naturalism to formal rationalism, converged with typographic legacy and advancing commercial printing practices to forge formidable ties between graphic design, industry and the public – relationships highly sought after by designers in today’s capricious market.

‘Dutch Graphic Design: A Century’, an ambitious, if overreaching, exhibition of rare posters and books, which opened in Breda in April 1993 and travelled to Frankfurt, Istanbul, Barcelona and Tokyo, stands as a testament to these and other aspects of the Dutch impact on graphic design’s evolution. In title alone, ‘A Century’ set forth a daunting challenge: to portray 100 years of cultural traditions, technical advances and underlying ideas, highlight the work of recent years to clarify Dutch design’s contribution to the discipline in 300 examples or less. Curators Kees Broos and Paul Hefting conceded subjectivity of choice. The show’s 117 posters and 178 books were meant to be read as a message from several designers to audiences abroad, a visual essay organised around the work of key protagonists of a given era which invited an appreciation of form, quality and aesthetics over content – a curiously contradictory premise now that culture resides in the image and increasingly looks to meaning to tether an impatient eye. An installation of scaffolds and glass display cases offered physical structure, but still the message suffered for want of a contextual frame. This was a pity. The show’s most provocative aspect – the point-counterpoint between the objective functionalists and expressive individualists whose concurrent evolution and coexistence have so enriched the Dutch graphic tradition – was alluded to but never fully developed.

Over the century, Dutch design has flourished in an environment of optimal yet oppositional conditions: a country the size of Maine built on reclaimed land with historic links to exotic East Indian isles; a consensual society of speculators and individualists that perceives design as a primary public good; a history of activist politics and long-term institutional patrons; and $3.5 (£2.3) million in annual government support to advance design among three design organisations serving a population of 15 million. The entire US, by contrast, makes do with government’s ever-shrinking $3.2 million annual funding of its National Endowment for the Arts Design Program.

Lacking a catalogue or expanded wall texts, however, visitors to this exhibition were deprived of historical reference and were left with little insight into the motivations of the ‘heroes‘ (and heroines?) of Dutch graphic design. It was therefore tempting to assume that design in the Netherlands evolved in a seamless, linear sweep across time, without pause at the interstices of change. The exhibition also failed to report the ways in which key cultural, political, spiritual and technical changes affected the visual expression of form. And, relying on visual examples alone, one could easily miss the pioneering role of the PTT as the century’s patron extraordinaire, engaging leading artists and designers – from van Royen in 1913 to Lebeau and Schuitema, Oxenaar, Dumbar and others in the present – to create an unparalleled model for design process and graphic identity.

Trained eyes would, of course, have spotted the clues in form alone. Or one could purchase the curators’ hardback book (review, Eye no. 10 vol. 3), which fleshed out the story and chronicled a much expanded Breda exhibition. But many of the show’s viewers at the AIGA, including an encouraging number of students, had not been rigorously schooled in the nuances of x-height to cap-height ratios, house style or the language of forms. There is in the Netherlands a long tradition of accessibility of design for mainstream audiences, and efforts to foster similar design appreciation in American audiences – to which this exhibition actively contributes – demand a corresponding responsibility not merely to expose but also to inform.

That said, there was much to delight. The show began with H. P. Berlage’s 1893 poster announcing the Amsterdam-to-London rail link which joined the Continent with the British Isles: the Industrial Age, which was to spur graphic design’s evolution from an applied art to a profession by the end of the Second World War, had begun.

This was followed by a series of classic posters: Jan Toorop’s Symbolist image for Delft salad oil (1893), Leo Gestel’s cubist Mercury, the god of commerce, for the Utrecht Trade Fair (1922), Chris Lebeau’s brooding Hamlet (1915), and Jan Sluijters’ fauvist nude for the Artists’ Winter Party (1919) typified the influence of Art Nouveau, Dadaism, Expressionism and the English Arts and Crafts movement on the turn-of-the-century search for style as the basis for functionalist and expressionist traditions.

The show moved quickly on through other periods and players: Paul Schuitema’s dramatic photomontages of 1930 for Nutricia Dairy Products and the Central Transport Workers Union; Piet Zwart, Theo van Doesberg and de Stijl, Van Krimpen, Willem Sandberg, Dick Elffers, Otto Treuman and Jan Bons in the 1940s and 1950s; Pieter Brattinga, Jan van Toorn, Anthon Beeke, Wim Crouwel and Gert Dumbar in the 1960s and 1970s; and Hard Werken and Wild Plakken in the 1980s.

The second half of the exhibition concentrated on work from the past 20 years which, while stimulating, was less well defined. Given the highly expressive, experimental and controversial spirit of recent times, some selections appeared uncharacteristically conservative. And as is often the case with far-reaching shows, the omissions were the most revealing. What could explain the curious absence of designers like Ootje Oxenaar, responsible for many of the banknotes and stamps to closely identified with Dutch design? Strangely, neither stamps nor currency were to be found – not even the stamp designed by Sandberg for the PTT in 1976 whose slogan, ‘Printing – a message from one to many’, is said to have inspired the exhibition.

In an ironic twist, the show ended with Wild Plakken’s award-winning poster for the 1989 Kulturreferat in Munich. Tilted ‘Encounter with the Netherlands’, it is stylised enigma – fused herring head and human ear, primary geometry and infinite space – an experiment in visual language where truth /stereotype, man/nature, sense/culture, form/technique speak to the multiplicity of opposites that is Dutch design. Having encountered the Netherlands in this extended prologue, however, the viewer is left with rather more questions than answers.

Moira Cullen, design writer and assistant professor, Pratt Institute, New York

First published in Eye no. 16 vol. 4, 1995

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.