Winter 1991

US designers with attitude

The Fourth Biennial AIGA National Design Conference

3-6 October 1991, Chicago Hilton, ChicagoTwelve-hundred graphic designers from over 30 regional chapters of the American Institute of Graphic Arts converged on Chicago in early October for a four-day conference dedicated to solving ‘Love, Money and Power: The Human Equation’. With over 90 speakers, and events timetabled from 9am to midnight each day, just surviving the onslaught of images and ideas tested a delegate’s stamina and allegiances. Who to see: Milton Glaser? Louise Fili? Drenttel Doyle? The days were divided into morning sessions in the Louis Sullivan designed Auditorium Theatre, with afternoons back at the Hilton, where four or five ‘breakout’ sessions ran simultaneously, and two evening slots for conversations and ‘affinity group’ meetings. (An affinity group consists of like-minded individuals gathering together to discuss the problems inherent in being like-minded.)

The conference was organised by Pentagram’s (then) most recently recruited partners, Paula Scher and Michael Bierut, with help from Steven Heller. If it was demanding on the delegates, the considerable strain on the organisers was borne with wit and a precise sense of timing. Scher and Bierut set the tone for the conference, proving that an event on this scale could be both thought-provoking and fun.

After the controversy generated at the last AIGA conference, ‘Dangerous Ideas,’ held in San Antonio, Texas, when Tibor Kalman singled out the Joe Duffy/Michael Peters partnership as guilty of designing solely for profit, the question was whether a conference entitled ‘Love, Money and Power’ could spark off the same heated, long-running debate. Would this first conference of the 1990s be a sop to the ‘new age’ spirit of peace and love? No need to worry. Bubbling just below the surface was a definite, uncompromising militancy. Michael Peters, in a belated reply to Kalman (conspicuously absent this year), identified this angry energy as the ‘very American syndrome’ of petty jealousy between members of the same profession hungry for money and power, and resentful of Peters’s success. Peters was even further off the mark when he asserted that making money represents ‘the highest order of creativity in design’. The record was put straight by Ralph Caplan when, in the closing address, he prayed that there was more to graphic design than packaging motor oil.

After the first day’s eulogies, which contained genuinely affecting accounts of how fledgling careers were guided by selfless mentors (Deborah Sussman: ‘I loved the Eames and they loved me’), the tone of the conference could most accurately be described as campaigning. This ‘attitude’ – to use the current street talk – appears to have arisen from the frustration that designers say they experience every day in their relationships with clients. Rick Valicenti offered himself up as the conference’s lucky mascot, or martyr, depending on whether or not you appreciated his self-presentation as cryptic Buddha and his unmitigated message. ‘We weren’t in the meeting,’ he bellowed, explaining why toothpaste packaging is so ugly. David Carson put his achievements at Beach Culture down to the fact that he had no client; it was just him and the editor, who allowed him virtually free rein. In a highly amusing diatribe against authors worried about the size of their names on his book jacket designs, Chip Kidd read extracts from correspondence sent to him at the New York publishers Knopf.

Despite this antagonistic tone, a plea was going out for designers to be taken seriously by the decision-makers, with strategies for seizing power being offered by many of the speakers. Josef Müller-Brockmann made the decision, at the beginning of a highly successful, 55 year-long career, not to work for any client who produced badly designed objects, or committed unethical business practices. His approach involved offering advice on how to improve the client’s product, often losing the commission in the process, and proving that principles will sooner or later cost a designer money. Müller-Brockmann’s ‘Don’t forget the message’ became a rallying cry for the conference.

Gran Fury have taken ‘attitude’ several stages further by becoming decision-makers themselves. This collective of ten AIDS activists have rejected what you could be forgiven for assuming was the underlying ethos of design – profit – and apply their skills as professional communicators to the fight against the ignorance and prejudice that aggravates the AIDS crisis. All of Gran Fury’s visual and verbal messages can be reproduced in a variety of media and disseminated on the streets, with no copyright restrictions. Four members of the collective took the stage and delivered their challenge in the most uncompromisingly political tone, inciting the audience to riot in defiance of the US government’s apathy.

At a conference, the reactions of the audience can sometimes be as revealing as the speakers. On several occasions in Chicago the audience seemed to respond more to the way in which the messenger packaged the message than to the implications of the message itself. This tendency was particularly obvious during the sessions which addressed the role of women in the design world. Cheryl Heller’s talk, ‘Woman/Design/Money’, provided ‘evidence’, through videotaped interviews with successful women, that the differences between the sexes are the product of centuries of myth-making, and that women can overcome sexism, having observed the oppressors’ weaknesses from the position of underdog, simply by asserting themselves. In a later session, a panel of equally successful women advocated playing the ‘male game’, and suggested that ‘feminine’ behaviour (i.e. being loyal to a particular firm and not climbing the career ladder through frequent job changes) is what keeps women underpaid and underappreciated. Dissension was eventually forthcoming, but extremely polite. A member of ‘Women in Design’, a Chicago support group set up in the 1970s, pointed out that although feminism is out of fashion, the only way to make real progress is through collective action and legislation. It is ironic that the discussion about equality for women in design was imbued with the very with the very same ideology of individualism that the rest of the speakers were trying so hard to conceal, or even eradicate, in an attempt to build collective power.

On Sunday morning we were offered hope in the shape of George Lois. Whether launching a foreign car in the US market – ‘I had to sell a Nazi car in a Jewish town!’ – or using the cover of Esquire magazine as a campaigning platform, Lois’s combination of commercialism, humour and integrity represented an approach that could still be feasible 30 years on. His observation that 99 per cent of design work is ‘crap’, but one per cent can change the world, put into perspective just how trivial, and yet how crucial, this business can be.

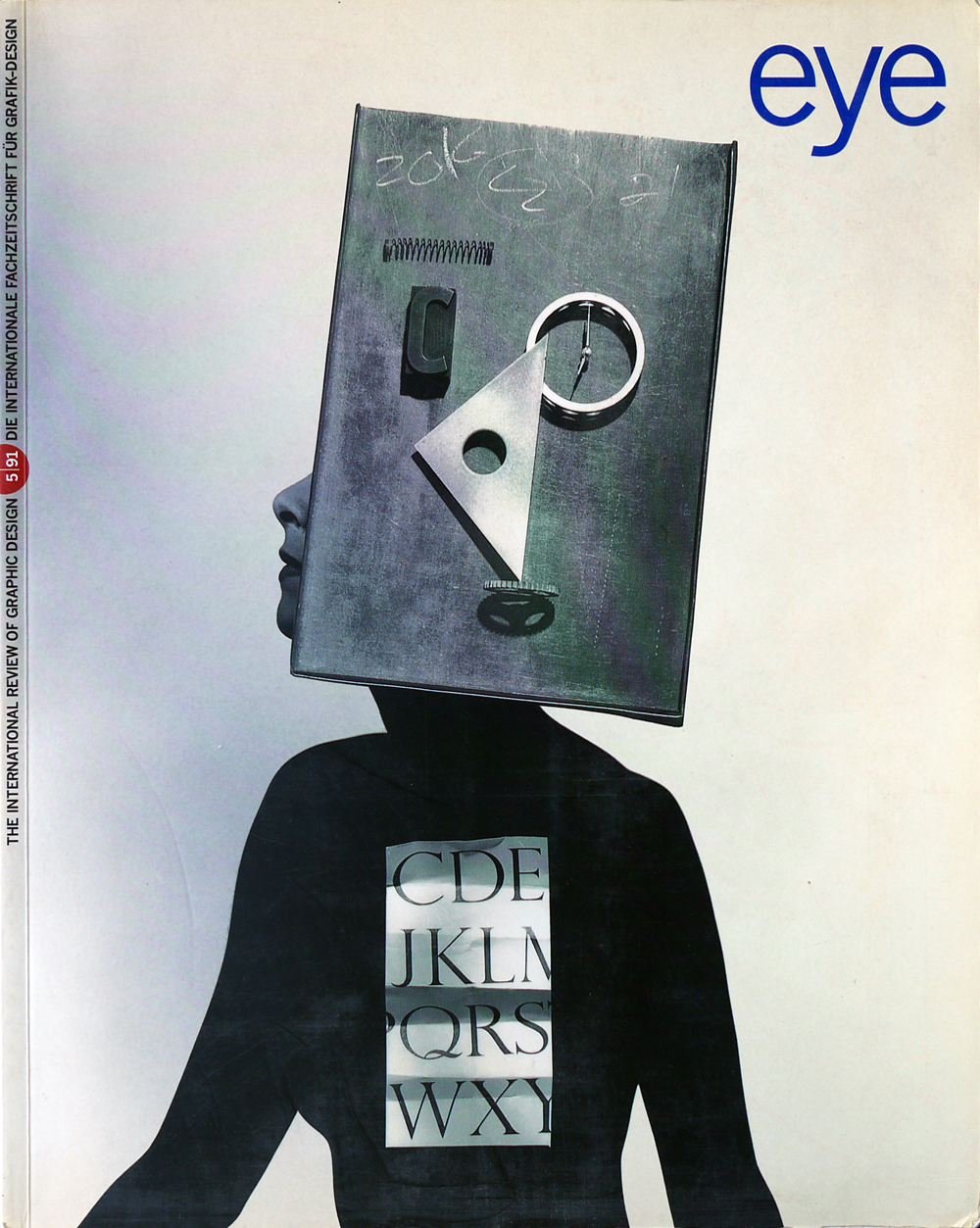

First published in Eye no. 5 vol. 2, 1991

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.