Autumn 2013

A cornucopia of Indian design

Dekho: Conversations on Design in India

Edited by Mohor Ray<br>Creative direction by Rajesh Dahiya, design by Abhijith KR, 2012<br>CoDesign.in, Rs2,100, $45, paperback

This anthology of interviews with Indian graphic designers gained exposure in the UK earlier this year when it was featured in the ‘Designs of the Year’ awards at the Design Museum in London. Published by the Delhi-based brand consultancy CoDesign, it offers a timely first-hand account of the state of graphic design in a country that has emerged as one of the world’s significant growth economies.

Early interviews in the book deal with typography. Both the late Professor Raghunath K. Joshi (who died at the age of 72 soon after he was interviewed for the book) and Neelakash Kshetrimayum discuss the challenge of adapting Indian scripts to typesetting technology, such as the metal printing press and Unicode, which were invented with the Latin alphabet in mind. The alternative visual paradigms of written language which both these typographers encounter in their work are illuminating, especially for Western readers who are often not familiar with the pictorial origins of their own alphabet. Joshi spent his career driven by the belief that ‘Essentially, writing is the rendering of sound and not the other way round.’

In his campaign for combined consonant and vowel sounds to be incorporated into single glyphs, he took a ‘phonemic’ approach to visualising language. Kshetrimayum has dedicated himself to the revival of Meitei Mayek, the script native to the Indian state of Manipur but which until the 1980s was for centuries subsumed under Bengali influence. Its sources are equally fascinating. The original characters derive from different parts of the human anatomy and the numbers were formed by the abstraction of foetal postures during its development.

A double-page spread in the next interview features two images of a cow. One is a black silhouette in profile drawn according to the rational conventions of information graphics; the other is a naïve sketch drawn by a person who cannot read or write. It is part of designer Lakshmi Murthy’s work with rural communities in Rajasthan and Gujarat to develop local communication and symbolic systems – often on the subjects of reproductive and sexual health. It is wrong to regard rural audiences as visually illiterate, she says. ‘The rural audience has a sharper perception of their environment and are keener to infer from indexical traces that the urban individual would neglect.’

The spoken word in Dekho reveals the rhetoric associated with contemporary design in India. This is often a combination of the abstract and removed language associated with capitalist enterprise and vivid personal accounts. Hence Ram Sinam and Sarita Sundar of design consultancy Trapeze talk of their aims ‘to conceive a communication solution that is multisensorial, using diverse media, but with a seamless flow of content’ while reminiscing of childhoods spent watching Kathakali at the temple and ‘the world of greasy gutted engines and the smell of fine wood shavings and the sound of looms, and mini adventures in the slush of the paddy fields and exploring the hills.’

In recent years, fuelled by critical or ideological motives, and by a sense of alienation from industrialisation and mass-production, Western graphic designers have taken recourse to bespoke and hand-made methods. Such renewed focus on the act of making has also been inspired by the characteristics of digital media and the desire to question the entrenched definition of design as occurring in a realm of conception as distinct from production.

In Dekho, there’s a sense that when Indian designers invoke such strategies, the recourse comes from more immediate and pragmatic social realities. Orijit Sen and Gurpreet Sidhu discuss the development of their People Tree brand, which enables India’s networks of still thriving craft-based producers and artisans to push the boundaries of traditional techniques.

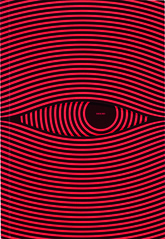

The cover of Dekho is printed in undulating black and fluorescent orange stripes. It conflates the graphic style of op art with curves evocative of Indian script. Elegantly die-cut at the centre in the shape of an eye to reveal the black circle of a pupil underneath, the book takes its title from the Hindi word for ‘to see’ (once Anglicised as the arcane British slang word ‘dekko’). Yet in the perspectives its contributors provide on the origins of human understanding, it could be called ‘to know’.

Veteran educator M. P. Ranjan invokes the framework of reflective practice and the work of Donald Schon and others when he encourages the development of ‘tacit knowledge’ … ‘hands on, minds on’. However most of the contributors in Dekho do not require a theory on which to hang their awareness of the fluid relationship between the mind and the body, and between rationality and intuition.

The sub-plot of Dekho is the story of the National Institute of Design at Ahmedabad. Founded 50 years ago and based on a seminal report by Charles and Ray Eames, every person in the book cites the National Institute as a formative influence, and the book contains many archival photographs of experimentation undertaken there. In 2013, as the Government of India embarks on an initiative to set up four new NIDs, one suspects a more detailed history of this institution and its pedagogy would be both rich and beneficial.

The final section of Dekho is given over to interviews with Anglo-European designers ‘presenting inspirational cues for contemporary design development in India’. While not new to Western readers, they are telling in their selection. Postmodern graphic designer, educator and author, Wolfgang Weingart writes: ‘Hot metal is a sensuous physical thing … Though I need machines, the creative component is my body … my best ideas were inspired by the mechanics of procedure. Rarely did I attempt to implement preconceived ideas.’ The book ends with Casey Reas discussing his fascination with emergence: ‘Emergence refers to the generation of (visual) structures that are not directly defined or controlled … Structure emerges from the discreet movements of each element as it modifies itself in relation to its environment. The structures generated through these processes cannot be anticipated …’

Such an ending suggests India is itself a model of emergent creativity (especially when compared to the command economy represented by China). This model is reflected in the design of Dekho. While based loosely on a two-column grid with body text set in Peter Biľak’s Greta, the design eschews a systematic approach. Each interview is treated individually. The book itself is a melting pot of illustration styles, typographic treatments and photographs, some black and white, some silhouetted, all of which share each other’s space on the page. It is not always easy to navigate – for instance, the gutter is often ignored and reproduction is not always of the highest quality – but the overall impression is one of exuberance and play, of a spirit of optimism, unhampered by constraints and less focussed on acts of undoing. In the meditations it offers on Indian contemporaneity and design, Dekho captures a significant, pivotal moment.

Die-cut cover. Creative direction: Rajesh Dahiya, design by Abhijith KR.

Top: spread from ‘Learning ground’ by M. P. Ranjan shows the author with a plaster model of a stackable chair.

Elizabeth Glickfeld, design writer, lecturer in design history, University of Kingston, London

First published in Eye no. 86 vol. 22 2013

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 86 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.