Winter 2026

Art of war and peace

Lee Miller

Tate Britain, London, 2 October 2025 to 15 February 2026. Curators: Hilary Floe and Saskia Flower. Exhibition design: Gatti Routh Rhodes. Catalogue design by Apfel (see Eye 99). Reviewed by John L. Walters

‘Lee Miller’ is a remarkable feat of curation. Outwardly a photography exhibition made of high quality photo prints, several rarely or never seen before, alongside books and magazines, the show decisively locates these pictures within their multiple contexts. It meshes each of its eleven rooms within the timeline of Miller’s personal and professional life. Currently at Tate Britain, the show will then travel to Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris (3 April to 26 July 2026) followed by the Art Institute of Chicago.

Like most people, Miller was many things. She was variously a student performer, a model, ‘artist’s muse’, photographer’s assistant, technical innovator, screen icon, professional portraitist, outstanding war correspondent (in both pictures and words), writer, mother, hostess, celebrity cook, competition whizz and music lover, whose story was dramatised (and somewhat fictionalised) in the 2024 movie Lee (see ‘An eye for a story’ in Eye 107).

The Tate exhibition demonstrates that Miller (1907-77) approached life and work as an artist, even when not consciously thinking and acting like one. There was no great plan. She never had a studio in one place for more than a few years. Yet the work emerged, from both professional practice and everyday life. Following her 1934 marriage to Egyptian businessman Aziz Eloui Bey, she stopped taking pictures for a while, only to resume in 1935, finding distinctive images within Egypt, her new homeland. One of many lucid captions in ‘Lee Miller’ explains that she had no darkroom in her Cairo home, so she used high street photo labs. These new constraints obliged her to create tightly cropped pictures in camera.

For designers, art directors and magazine enthusiasts, there’s the pleasure of seeing her wartime photography for Vogue beautifully printed and mounted alongside the grainy reproductions of her fashion and beauty spreads, complete with a tiny, all-caps credit line.

‘Essayez!’ Lee Miller in Jean Cocteau’s Le sang d’un poète. Exhibition installation photo by Sonal Bakrania for Tate.

It is to the curators’ credit that they balance out the different aspects of Miller’s oeuvre with style and sincerity. A three-minute extract from Jean Cocteau’s Le sang d’un poète [The Blood of a Poet], described in a 1965 Vogue article as ‘perhaps the first of the underground movies’, shows Miller starring as a living statue, urging the hapless poet to: ‘Essayez!’ [Try!], as he contemplates entering a mirror. The room entitled ‘Dreaming of Eros’ displays nudes credited jointly and separately to Miller and her mentor Man Ray. A restored film clip, Autoportrait ou Ce qui manque à nous tous (1930) shows a soap bubble inflated by an off-screen Ray, followed by Miller, who unwraps and suggestively strokes a Brâncuși sculpture with a seductive look that collapses into laughter.

Lee Miller’s Rolleiflex camera and uniform on display alongside prints and magazines of her war reportage. Installation photo by Sonal Bakrania for Tate.

A challenge for the exhibition is that some of the images are overly familiar from previous exhibitions and books, not to mention the trove of material shown in rotation at Farleys House & Gallery in East Sussex, home to the Miller archives and the former home of Miller and her second husband, artist Roland Penrose. However the advantage of seeing so many pictures assembled in one show is that you can see the special genius of Miller’s gaze.

The Rolleiflex cameras she used (one is displayed in a cabinet, alongside her war correspondent’s uniform) allowed her to get close and engage with subjects as she snapped them from midriff level. Men, however admirable, are treated with humour, as boys with toys, or with cautious admiration. Women are generally accorded greater dignity and power, whether dressed in fashion, factory clothes or protective gear, as in Fire Masks (1941).

Model Elizabeth Cowell wearing Digby Morton suit, London, 1941. In 1936, Cowell was the first female TV announcer. Top. David E. Scherman dressed for war, 1942. Young Life photographer Scherman (1916-97) was Miller’s wartime accomplice. © Lee Miller Archives, 2025.

The wit that suffuses even her rubble-filled pictures of the London Blitz subsides as we turn to her war reportage, which shows the anxiety of civilians, soldiers and medics under attack. Incomplete layout proofs show how Vogue integrated her pictures and vivid caption-writing in a tightly edited, empathetic picture feature about a field hospital: ‘A few rolled up the sides of their wall tents to let the Normandy sun pour in’; ‘Under close guard, German prisoners are often used as litter bearers ….’ Contact sheets on display reveal the consistently high standard of her work in the face of discomfort and danger.

The mood changes yet again as we enter a room entitled ‘Believe it’, which warns visitors of distressing content and forbids photography. This displays pictures from Dachau and Buchenwald, where she shot an enormous sign reading Jedem das Seine [To each his own] from behind. There are unflinching images of the enemy: an SS officer beaten up by prisoners; guards who stole civilian clothes in the hope of escaping; the serene corpse of the daughter of a Leipzig official who had killed his family before committing suicide; the charnel house evidence of Nazi crimes.

Miller typically avoided explicit images of violence, using Surrealist metaphors to imply death and disfigurement, but her disgust at the atrocities, in the face of 1945-era ‘fake news’, made it imperative to show that the Holocaust had taken place. Grim humour is never far away, as shown by the celebrated pictures of Miller and fellow photographer David E. Scherman (of Life), each enjoying a staged soak in the bathtub of Hitler’s Munich apartment.

The final room, ‘Artists & Friends II’, shows work from the last 30 years of her life. She married Penrose in 1947, gave birth to a son, Antony, and moved to Farley Farm. Fellow artists blossom under her sympathetic gaze. Picasso, of whom she took around 1000 portraits, looks almost avuncular; Dorothea Tanning, portrayed boldly in 1955, looks more confident than any male artist on display.

Miller’s jokey Vogue feature from 1953 shows famous friends (Saul Steinberg, Max Ernst, etc.) trying out farm work. Another feature from 1965 deals with her ‘second fame’ as a cook. One impression of Miller’s life is of hyperactivity, of someone driven to keep making things, engaging with people and reinventing herself.

Yet the lasting visual memories of this huge exhibition are more subtle. The 1930-32 portrait of Sirène (Nimet Eloui Bey), recently found in Cocteau’s archives, shows the Egyptian beauty (Eloui Bey’s first wife) with splayed-out hair that anticipates Elsa Lanchester’s in Bride of Frankenstein (1935). Many images – of the bombed-out Vienna Opera House, of Romanian performers with drums, clarinets and dancing bears, of the scorched Egyptian landscape – are full of quiet resonance. The recently discovered Photomaton self-portrait (ca. 1927) show that these qualities were there from the beginning: stillness, wit, controlled energy and honesty in the face of human folly, oddness and accidental beauty.

John L. Walters, editor of Eye, London

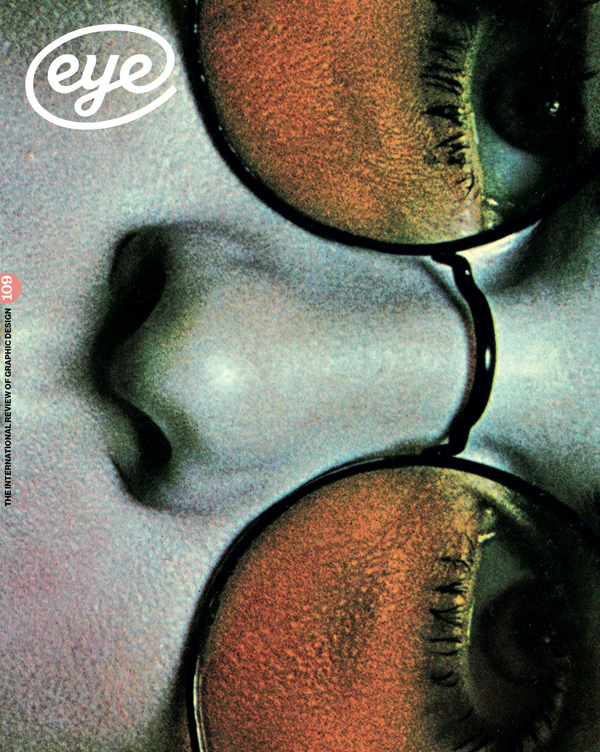

First published in Eye no. 109 vol. 28, 2025

Photomaton self-portrait of Lee Miller. Installation photo by Sonal Bakrania for Tate.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.