Winter 1994

Copyright will tear us apart

Sumner Stone

David Berlow

Petr van Blokland

Matthew Carter

Jack Stauffacher

Porter Garnett

W. Starling Burgess

Stanley Morison

Mike Parker

Critical path

Reviews

Typography

ATypI Congress

San Francisco, 9 to 12 September 1994 Reviewed by Robin KinrossWhen the Association Typographique Internationale was founded in 1957, it was essentially a typesetting manufacturers’ organisation. Its main concern was the protection of copyright in typeface designs. Cultural and educational aims were added in, thus reproducing the nice mix of grubby materialism and human culture that characterises typography. Besides these concerns, ATypI acts as a peg on which to hang an annual congress for the international typographic community. The main functions of these meetings are networking, displays of wares, and deals of all kinds, including ATypI’s self-preservation. In between, some lectures are given.

ATypI has always had its troubles, but in recent years it has been through especially choppy waters: rows and resignations, glossed over in anodyne, badly desktop-published minutes. At the root of these troubles is the present disruption of the nature of typography through technical change. Copyright in typeface design has been challenged to its roots. The manufacturers – radically altering in nature and number over the past twenty years – still struggle to retain hard notions of property in the face of digital deliquescence.

These difficulties came to a head at the 1991 meeting in Parma, when a new president, Ernst-Erich Marhencke, was sprung on the organisation by the ageing German-Swiss grouping that has so far run it. Mark Batty of ITC in New York had been expected to be elected, a move that would have reflected the new US dominance of the field. Some days after this, Marhencke left his position at Linotype-Hell and now carries on as president with no connection to typography.

The crisis intensified in 1993. The congress that year had a lecture programme on the theme of ‘The Alphabet goes Multimedia’ which promised to be an event of head-in-the-clouds nothingness. Sponsors began to complain. An alternative, hands-on gathering was organised a rival, outside the official congress: computers would be used rather than waffled on about. This was TypeLab, a self-determining enterprise set up by Dutch typeface designers, which had run successfully in Amsterdam that July. Eventually a compromise was struck. TypeLab was drawn into the official congress and the lectures went ahead, but only after a personal subvention by ex-president Martin Fehle.

This year’s meeting in San Francisco promised better. The lecture programme was arranged by Sumner Stone: a real typeface designer and a Bay Area local. TypeLab was again part of the congress. It is now incorporated as a firm – to protect its name and concept against a growing number of rip-offs – and has extended beyond the Netherlands, with David Berlow (of the Font Bureau in Boston) as co-director along with Delft-based Petr van Blokland.

In a big-bucks hotel near Union Square, three sessions ran in adjacent rooms. There were lectures on calligraphy and writing, reflecting the strange boom in this activity on the West Coast, where a credit in calligraphy is a necessary part of every engineer’s training. Then there were talks about typography. Among these I will remember best a faltering but utterly authentic discourse by Jack Stauffacher on an earlier San Francisco printer, Porter Garnett. ‘Porter was a special guy’: like Stauffacher, a maker of good work, and of what is still there to be striven for in typography. Among the other talks in this strand, Matthew Carter’s lecture on experimental type design through history had much contemporary relevance. ‘The sincere form of flattery is deconstruction,’ he said of a student exercise in slashing up his Galliard typeface. This brought us back to the grumbling issue of copyright. Anyone with a copy of Fontographer can deconstruct an available typeface and junk it on the world. Let them. Skill-free schlock will eventually find its own level.

Down the corridor in the TypeLab there was a lot going on: keyboards, mouses, pens, stone-cutting, punch-cutting, drawing letters on paper, designing and producing the daily newspaper, and much hanging out, some of it no doubt time-wasting, some rewarding. Among the more formal contributions was a talk by Mike Parker on W. Starling Burgess, an American designer, primarily of yachts, who seems to have had a hand in the design of a typeface for the US Lanston Monotype company which uncannily resembles Times Roman. This was in 1918, some thirteen years before the English Monotype company launched the typeface, its designer credited to Stanley Morison. This again raises awkward copyright issues. In a series of historical revisions since the 1970s, Morison’s role in Times had been downplayed. But now, just when we had got used to seeing it as an anonymous drawing-office design, Parker proclaims Times Roman to be an Edwardian old face and the work of a great American designer.

The big news at the congress was the arrival of TrueType GX (Graphic Extension) fonts (see ‘Tools’). By the end, and especially after a panel discussion between designers, most people had just about sorted out what this new thing is, and how it relates to PostScript and Type 1 fonts. A few people wondered aloud what the use of GX is. Is it just to bring us swash characters and ligatures? At the closing session, someone lamented the absence of non-western typography – and this in a city with a huge, now indigenous far-eastern population. Despite efforts by TypeLab, no one clearly made the connection between far-eastern scripts – often with massive character sets – and the capacities of GX fonts.

The final event was the ATypI Annual General Meeting. This was open to non-members – a good thing too, since only 49 of the 450 people attending had stumped up the annual membership fee of 160 Swiss Francs (which brings no rewards except feelings of benevolence and frustration). We ran through some funny procedures. Vital amendments to the constitution had been sent out from the ATypI office, but had not been received by members. They were read out and instantly approved. Votes in a secret ballot were put into envelopes bearing the voter’s name, and then counted only by the president. In the muddle over procedure, one member’s votes were not counted. His votes (he told me) would have blocked the re-election of a key member who scraped in with the minimum 25.

ATypI

will stagger on for a while, in name at least. In a special

conference offer, masterminded by font price-cutting executives,

membership fees were halved. More than 70 people joined. But next

year’s event in Barcelona threatens, like 1993, to be another

marriage of two partners not on speaking terms. So,

like the copyright laws it clings to, the increasingly empty husk of

the old ATypI must fall away. What is still useful – the

networking, the deals, the explanation and exploration – will find

its own form.

Robin Kinross, author and publisher of Fellow Readers, London

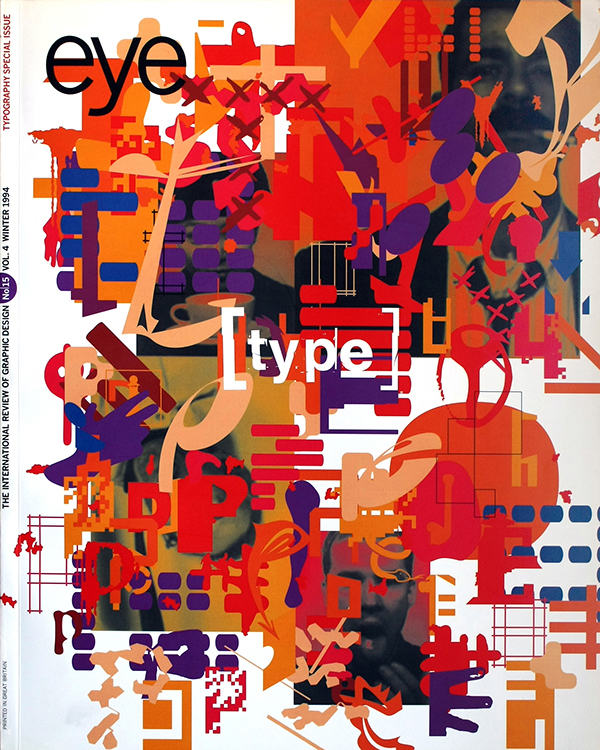

First published in Eye no. 15 vol. 4 1994

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.