Winter 1994

Defending the reader’s rights

Fellow Readers: Notes on Multiplied Language

Robin Kinross. Hyphen Press, £4.50. Reviewed by Andrew BlauveltThe power of self-publishing becomes fully manifest in Robin Kinross’s latest title, Fellow Readers: Notes on Multiplied Language. Issued by Kinross’s Hyphen Press and designed by the author, Fellow Readers is a short, 32-page book that attempts to correct the theoretical posture of numerous designers who now subscribe to notions borrowed from post-structuralism and deconstruction. Kinross’s text outlines his arguments against the intellectual dependency of those designers and their philosophies, as expounded in the design press of both Britain and the US, particularly within the pages of Emigre and Eye.

Kinross undertakes his attack on a theoretical front. He argues that one of the founding principles of linguistics is misread and misapplied by these designers and their sympathisers. Furthermore, he objects to the roles designers and readers are assigned in such theories, a proposition he extends into a discussion about the social context of reading as a communal endeavour.

Kinross tersely reduces the philosophy of his opponents to: ‘We know the world only through the medium of language. Meaning is arbitrary. Meaning is unstable and has to be made by the reader. Each reader will read differently. To impose a single text on readers is authoritarian and oppressive. Designers should make texts visually ambiguous and difficult to fathom, as a way to respect the rights of readers.’

Central to his discussion is the concept of the arbitrary nature of the linguistic sign. Kinross provides a re-reading of Ferdinand de Saussure’s Course in General Linguistics, which first put forward this concept. The confusion at this juncture is the jump Kinross makes between the contention that ‘meaning is arbitrary’ and Saussure’s conception that the linguistic sign is arbitrary. The difference is fundamental. Attempting to prove that the linguistic sign is not arbitrary, as Kinross asserts, does little to disprove the idea that meaning is arbitrary. Linguist Emile Benveniste, in his examination of Saussure, found that the arbitrary, rather than being held within the sign, exists outside it: that is to say, meaning extends beyond the sign into the material reality of communication – the particular medium or vehicle, the subjectivity of readers, the context, and so on.

Ironically, Kinross parallels in many respects the re-reading of Saussure undertaken by Jacques Derrida in Of Grammatology, an important text on deconstruction. In particular, both authors expound on the lack of attention Saussure paid to the materiality of language – its visual expression as writing and printing – in favour of the abstract and immaterial quality of sounds and concepts.

It is the interpretation of texts that should be central to Kinross’s discussion. Indeterminacy and determinacy of meaning are key disputes within literary criticism, which involves the interpretation of texts. Advocates for a determinacy of meaning within a text attempt to show that there is a plausible and fixed interpretation, and often refer to the author’s intention and / or to an intensive examination of the text itself.

The evidence suggests that there is an indeterminacy of meaning attributable to the text; that hopes for a fixity of meaning are countered by the uneven competency of readers and their experiences, while any recourse to the author’s intentions gives way to the problem of the ‘absent author’ in reading. Kinross counters: ‘The idea that design should act out of the indeterminacy of reading is a folly. A printed sheet is not at all indeterminate, and all that the real reader is left with is a designer’s muddle or vanity…Afar from giving freedom of interpretation to the reader, deconstructionist design imposes the designer’s reading of the text onto the rest of us.’

Here Kinross invokes the social responsibility of the designer to facilitate the production of texts that enter the world multiplied and disseminated, an extension of their life beyond any single author or designer or reader. His argument presupposes some ideal or optimal balance between design’s visual presence and its transparency: the age-old typographic dualism of self-expression and non-expression. Design, whether ‘self-expressive’ or ‘subservient,’ cannot help but act out the indeterminacy of the text – a point made clear by Kinross in his essay ‘The Rhetoric of Neutrality.’ Perhaps it is a matter of degrees, not extremes.

When Kinross declares that the imposition of the designer’s reading on the work comes at the expense of readers’, he gives too much power to designers to foreclose readerly interpretations and too little power to readers to negotiate the designer’s inevitable intervention. What is ignored by both sides of the typographic debate is a varied notion of interpretation that sees reading as an active process through which readers engage texts and negotiate meanings – neither solely as passive and powerless, nor completely free from contexts or the codes of communication invoked.

Although Kinross rightly argues that some theorists erroneously treat all ‘texts’ as literary works, he is equally guilty in his monolithic treatment of his opponents, which fails to distinguish varying communicative contexts. After all, there is a difference between a traffic sign and a cultural poster. We are offered no examples and no analysis of specific pieces of graphic design which supposedly fail, only an appendix of ‘voices advocating enforced undecidability.’

Kinross’s

arguments are strongest when they remind us of the social agreement

that is communication and the role design can play in the critical

discourse of a society. They are weakest when they attempt to deny

outright the applicability of language theory to graphic design. What

needs to be recuperated from Kinross’s text is the notion that

language theory, social theory and cultural theory can provide

graphic designers with valuable ways of understanding their practice.

What we must heed is the optimistic notion that we need to recover a

certain sense of the public sphere as a space for critical dialogue,

where debate is central to democratic ideals. Kinross advocates a

rather conventional role of designer-as-conduit, albeit with a notion

of design for social good, while at the same time offering himself in

a rather unconventional combination of roles: author, designer,

critic and publisher. His actions speak louder than words.

Andrew

Blauvelt, assistant professor, North Carolina State University

First

published in Eye no.

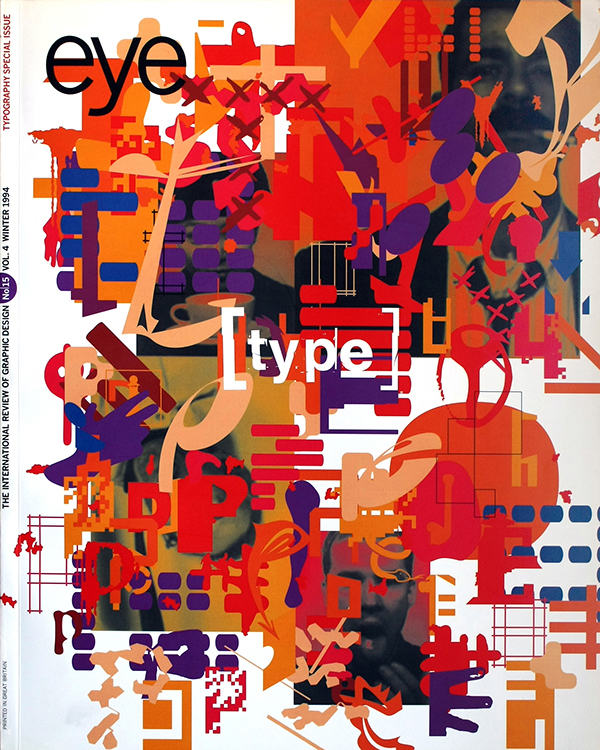

15 vol. 4 1994

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.