Summer 2008

Manual transmissions

Design and Science:The Life and Work of Will Burtin

By R. Roger Remington and Robert S. P. Fripp<br>Design: Chrissie Charlton & Company <br>Lund Humphries, £35 / $70<br>

Will Burtin was one of the pioneers of twentieth-century American graphic design, but he strode across a landscape very different from today’s. His is the period of mid-century Modernism: after the Second World War but before Vietnam and the 1960s changed US culture. Back then, people had more faith in the idea of progress and were less sceptical about capitalism and the corporations Burtin worked for. Atomic energy and drug development were causes of optimism: science was seen as having the potential to advance mankind rather than destroy it. This illustrated biography sets out to show how Burtin used design to explain scientific ideas.

Like so many of the architects and designers who shaped America in the 1940s, Burtin was an émigré, born in Cologne in 1908. His growing reputation in Germany meant first Goebbels and then Hitler asked him to head the design team at the ministry of propaganda. He and his Jewish wife, Hilde, fled the Nazi government in 1938 and apparently never spoke German again.

Burtin brought his contemporary European design influences to America. He was scientific and analytical about the act of communication: ‘To facilitate understanding is the task of design,’ he said. As America entered the war, Burtin was drafted into the army and designed gunnery training manuals for the air force. Airmen’s lives depended on the quality of his information design and these projects encapsulate his future work: research a subject so you understand it and can explain it graphically to others using photography, diagrams and text. He believed that ‘beauty is not necessarily a matter of form or style, but the result of order achieved.’

In 1945 the business magazine Fortune had him released from the army to be its art director. Through double-page information graphics explaining themes such as how coal is used in industry or television transmission, Burtin used his art direction skills and those of artists such as Max Gschwind and Alex Steinweiss to explain how things worked ‘to convey meaning, to facilitate understanding of reality and thereby help further progress is a wonderful and challenging task for design.’

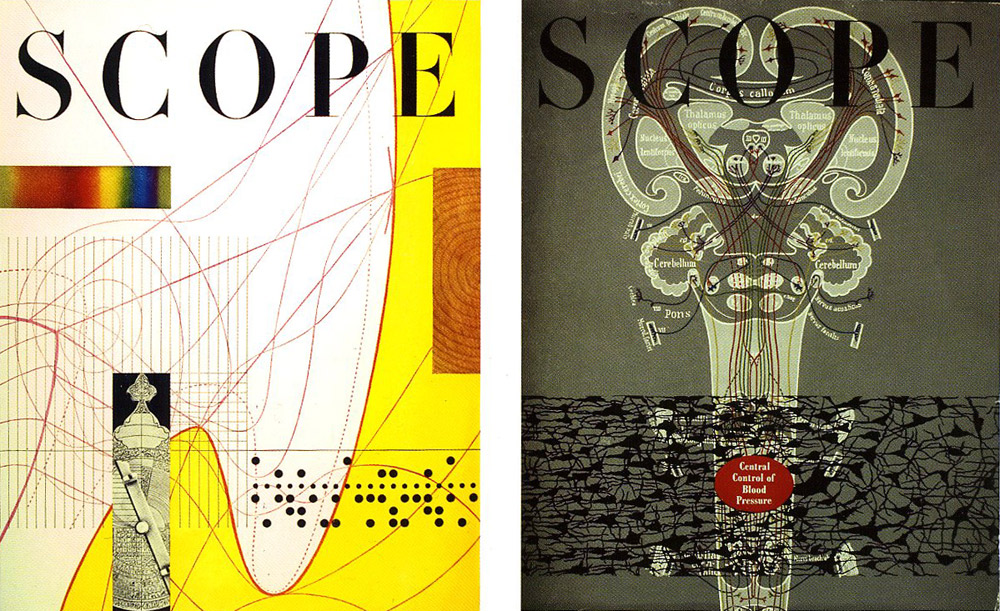

Running his own studio by 1949, Burtin worked for the design-aware parts of us industry: Parker Knoll, Herman Miller, Eastman Kodak, IBM, Union Carbide and the pharmaceutical company Upjohn. Burtin had a 30-year relationship with Upjohn, designing the first cover for its doctors’ magazine, Scope, when he arrived in New York and becoming its art director in 1948. In 1947 he had redesigned first Upjohn’s original mark, replacing it with a text-only logo, and then all the company’s drug packaging. Burtin was running a corporate identity programme before the phrase was invented.

It was for Upjohn that Burtin created the huge travelling ‘exhibit sculptures’ that dominated the latter part of his career. The studio researched and created these massive 3D models (the first, Cell, was a million times life size) and built them out of new materials such as Plexiglas. In an electro-magnetic, pre-computer age these scientific visualisations spread the Upjohn brand to doctors at medical conventions and to the general public at world’s fairs.

Remington and Fripp capture the personalities of Burtin and those around him, a close world of leading designers and their educated clients. The text is personal and anecdotal, but does not always give a picture of the wider context in which Burtin operated. Given Burtin’s own graphic sensibilities, the design of the book is conventionally classical: pictures on a page rather than any graphic narratives or changes of pace. Designers will hunger for more and bigger illustrations of the actual work. Ezra Stoller’s evocative images of the big exhibits tell part of the story, but the print work for Fortune and Scope isn’t shown large enough to appreciate the detail (although there may well be copyright issues). There is a history of contemporary information design, from print to online, waiting to be written: when it is, Will Burtin will figure as one of its founding fathers.

Top: Burtin’s cover for Scope magazine, Spring 1953.

First published in Eye no. 68 vol. 17 2008

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.