Spring 2025

Reality is the killer app

various designers

François Morellet

Brion Gysin

Reviews

Technology

Events and exhibitions

Electric Dreams – Art and Technology Before the Internet

Tate Modern, London. 28 November 2024 to 1 June 2025. Curators: Val Ravaglia and Odessa Warren with Kira Wainstein Reviewed by Joel Gethin Lewis

‘Electric Dreams’ begins with a punch card-based collage and finishes with a real-time installation that places the viewer in the artwork that they themselves are creating. The progression of artworks over fifteen rooms on the third floor of the Turbine Hall mirrors technological change over the four decades that the show spans. As complex electronic functionality evolved in society it is reflected in the artworks that were produced, or perhaps it’s the other way around?

It is fitting that the opening work, Vera Spencer’s Artist versus Machine, uses punch cards, a technology that enabled binary instructions to be passed to the Jacquard loom (see Eye 70), which in turn inspired Charles Babbage and allowed the world’s first computer programmer and hacker Ada Lovelace to dream of machines ‘acting upon other things beside number’. What is interesting about the period covered in this exhibition is that the works shown deal with technology as a material itself, rather than the enabler of production – ‘materialising the invisible’ as the brilliant diagram that sits next to Spencer’s work states. What the diagram shows is the complex web of relationships between artists, industry and institutions that resulted in the smorgasbord of works packed into this upper floor of an abandoned Victorian cathedral to electricity.

I have spent the past 30 years fascinated by the relationship between people and technology – particularly the ways in which technology can be used to make new relationships possible between people. Technological advances have always enabled new forms of expression – from the invention of linear perspective in Renaissance Italy to the nineteenth-century paint tubes that enabled Impressionism to drag painting from the studio to the outside world. This relationship between art and technology has always existed, all the way back to the use of fire to enable drawings on the wall of a cave.

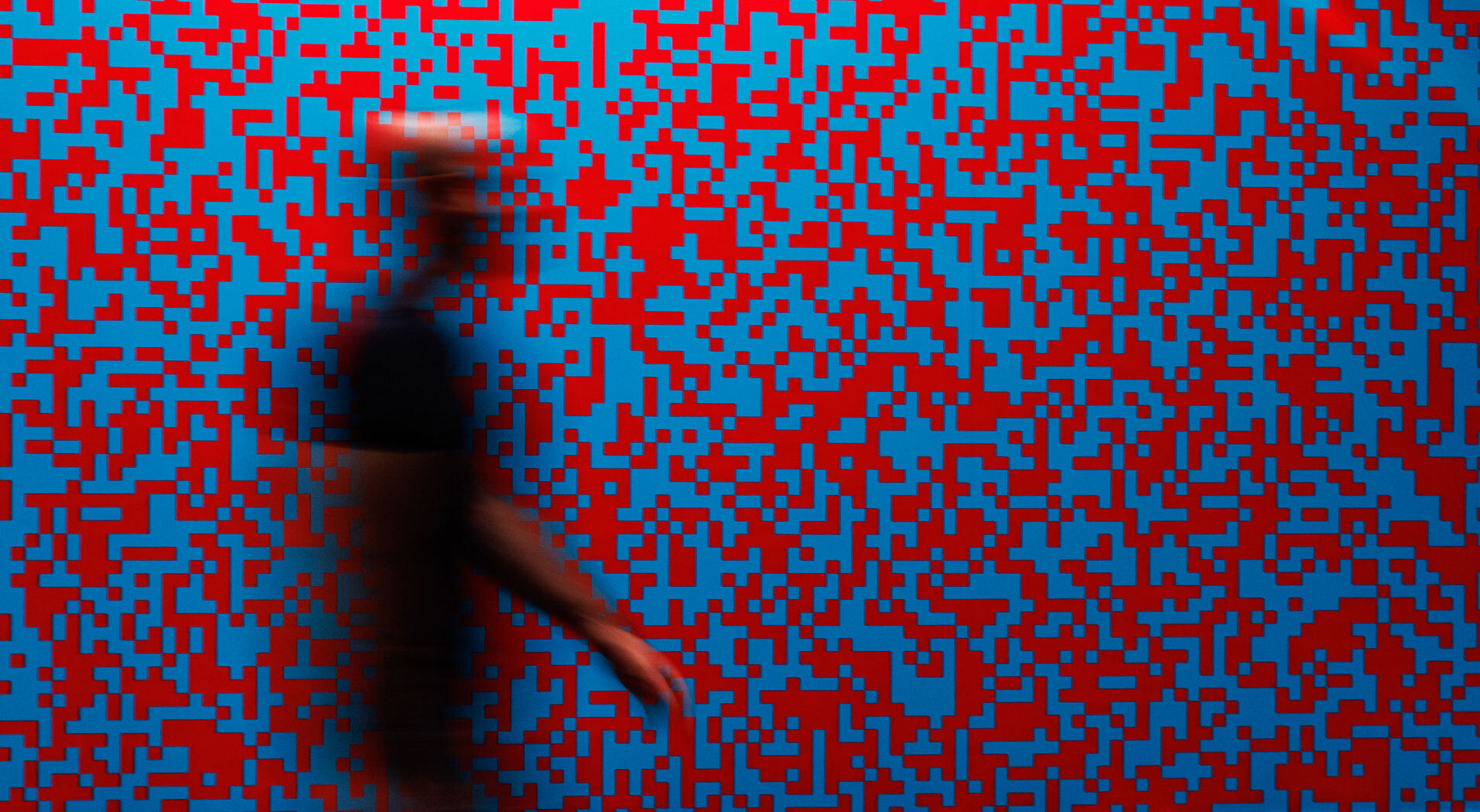

The exhibition strikes a balance between presenting a linear series of works and giving over entire spaces to immersive experiences. When I visited the room dedicated to Carlos Cruz-Diez’s Environnement Chromointerférent, it was packed with people of all ages interacting with dizzying vertical patterns projected over walls, balloons and boxes. There are other more meditative moments, however, including Otto Piene’s Light Room (Jena), Brion Gysin’s Dreamachine and Tatsuo Miyajima’s meditations on the ‘study of models of the world, of outer space, of time and of human society’. If ultra- high-contrast interference is more your thing, François Morellet’s Random distribution of 222,048 squares using the π number decimals, 50% odd digit blue, 50% even digit red certainly does exactly what it says on the tin, but don’t miss fellow GRAV artist Julio Le Parc’s Four Double Mirrors, a portent of social media image filters and an echo of fairground halls of mirrors.

As a child, I spent years campaigning for Father Christmas to deliver an Amiga to my small corner of rural Wales, so it was extraordinary to see several works created using Deluxe Paint – the very software I used for looping animations in the 1990s. In an interview published in the engaging show catalogue, artist Suzanne Treister relates how she started producing her ‘Fictional Videogame Stills’ series after visiting Soho’s arcades, including SegaWorld in London’s Trocadero. Treister goes on to reference William Gibson’s Neuromancer giving her the impetus to start making work, another echo of my own journey. The reference to Gibson made me think of one of my favourite quotes of his (first posted on Twitter): ‘Very creative people get atemporal early on. Are relatively unimpressed by the “now” factor, by latest things. Access the whole continuum. Less creative people believe in “originality” and “innovation”, two basically misleading but culturally very powerful concepts. Your bleeding-edge Now is always someone else’s past. Someone else’s ’70s bellbottoms. Grasp that and start to attain atemporality.’

The curators have not included anything from the ICA’s 1968 ‘Cybernetic Serendipity’ (see Eye 88), but have instead highlighted lesser known centres of activity, including groups in Argentina, Japan, India, France and what is now Croatia. DIY culture and its relationship to technology is highlighted by the inclusion of archive material from the publications Whole Earth Catalog (see Eye 78), Radical Software and Guerrilla Television Revisited, with Sarah Cook using the exhibition catalogue to query the individualistic ethos of the mercurial Stewart Brand: ‘We still need the artist-programmers and the programmer-artists to remind us not just that we should DIY, but that we should DIWO (Do It With Others) if we really want to challenge the corporate technology-dependent world our corporeal bodies live in.’

I have always said that the real world is the killer app. Walking from room to room in this brilliant exhibition and watching visitors engaging with each other in new ways as a result of the works on show reinforced that these loops of experience, opportunity and sheer luck are what makes us human. ‘Electric Dreams’ demonstrates that this was all happening before the World Wide Web and its offspring ensnared our attention, something to which we should all pay attention.

Joel Gethin Lewis, interaction designer and lecturer, London

First published in Eye no. 108 vol. 27, 2025

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.