Winter 1994

Theory must be put to work

‘And Justice for All …

Edited by Ole Bouman. Jan van Eyck Akademie Editions, HfI50.00 Reviewed by Michèle-Anne DauppeDutch art and design academies, unlike their UK counterparts, can be relied on to produce quality self-promotional publications. Even if you had never heard of the Jan van Eyck Akademie in Maastricht, the design of this book, a post-symposium publication, would make you want to find out more. This particular institution occupies a highly privileged status. With the legendary Jan van Toornas its director, it offers postgraduate study in the fields of fine art, design and theory. Its programme is radical and progressive in intention, with an emphasis on social responsibility. Entitled ‘And Justice for All…[sic], the symposium, held in 1993, addressed the ‘relationships between art, design, theoretical reflection and public space.’

The book is divided into three thematic sections: the public sphere, the notion of the avant-garde, and the search for personal strategies in visual culture. All are related, we are informed by the editor Ole Bouman, to the basic Kantian questions: ‘What can we know, what can we do, what can we hope?’ It is designed by Felix Janssens, a participant (the term for student) at the academy. Each section contains papers from the symposium interspersed with visual statements referred to as ‘artists pages.’

The editorial presence is high profile. In addition to the main introduction, each section begins with an editorial, identified typographically by the use of larger type arranged landscape. Bouman’s authorial voice also interacts with the text: running in the margin alongside the papers, or sometimes at the end, are questions and reflections by the editor followed by answers from the authors. In some cases this device works well: where the directness of the answer (never the question) comes as a welcome relief from the tone of the text, or where antagonism breaks out. In one such acid exchange, in reaction to criticisms the editor makes of him, Hugues Boekraad states: ‘I can only conclude that my approach must fall outside the scope of fashionable postmodernism. I take that as a great compliment.’

The symposium’s aims – to further the project of bringing theory to practice and to debate the social – are admirable, an ambitious and welcome change from design conferences where speakers assume the orthodox position of the ‘professional,’ refusing to politicise their practice and centring debate around their last job. Unfortunately, the aims have not been convincingly fulfilled. The majority of the papers, predominantly philosophical in framework, offer serious considered thought, but their abstract concerns seem misplaced in an institution which positions itself as ‘oppositional.’ The section on the avant-garde, for instance, is in the main quite remote from its colourful subject. The two most accessible papers are a flawed essay on consumption by Stuart Ewen and a compelling discussion of media activism and the Gulf War by Martin Lucas. At the other end of the scale, Hauke Brunkhorst’s elegant philosophical survey of the modern idea of the public sphere, like man other papers, requires several readings.

The contribution most relevant to graphic design is by Van Toorn himself: ‘Thinking the Visual; Essayistic Fragments in Communicative Action.’ Here Van Toorn describes what he sees as the current complicity of designers who have been ‘unable to stay out of’ an ‘ongoing process of colonisation of the media.’ He identifies their lack of awareness of their role and – citing the philosopher and social theorist Jürgen Habermas’s concept of ‘communicative action’ as a liberating force – elaborates on interventionist strategies. In defence of the anticipated criticism that he privileges politics over aesthetics, he neatly states: ‘I think what matters is that the discipline of design should politicised by giving it a genuine social orientation once again – an orientation that goes further than the established idea of social efficiency in the sense of functionalist aesthetics and semantics.’

By contrast to the academic approach of many of the papers, the content of the editorials is pacey and polemical. Apparently utterly seduced by the rhetoric of postmodernism, Bouman makes grand generalisations such as ‘The content has evaporated and everything can thus be mutually compatible,’ or ‘The image comes before imagination. Intentionality has vanished.’ No doubt an attempt to liven up the proceedings, his attention-grabbing, eclectic approach unfortunately courts superficiality. Issues such as the self and the ‘other,’ signification, macro / micro narratives and interventionism are raised but not examined; interesting observations are simply tossed into the theoretical minestrone he conducts.

The ‘artists pages’ are visual contributions produced by participants during the course of the year, demonstrating that the themes of the symposium continued to provoke discussion long after the three-day event was over. According to the introduction: ‘This work shows how in a profit-orientated visual culture, a non-instrumental image potentially has the vitality to stand its ground.’ This makes the work sound more interesting that it is. These ‘artists pages’ function neither as illustration to the themes of the text nor as communication statements in their own right. They appear as a dispersed collection of images, decontextualised, often with no guide even as to their scale. At best they are obscure, at worst art-school indulgence.

For opponents of theory, it would be easy to dismiss the tone of these proceedings as over-intellectualised and impenetrable. It is possible, however, for academic and intellectual enquiry to be more accessible and relevant: theory has to be made to work, to be applied. If Van Toorn is interested in the ‘complex relationships of socio-historical conditions,’ then why the absence of detailed historical research into particular sets of conditions? Questions of methodology need to be debated and thought through, but it would make more sense if this were done in the spirit of clarification rather than obfuscation.

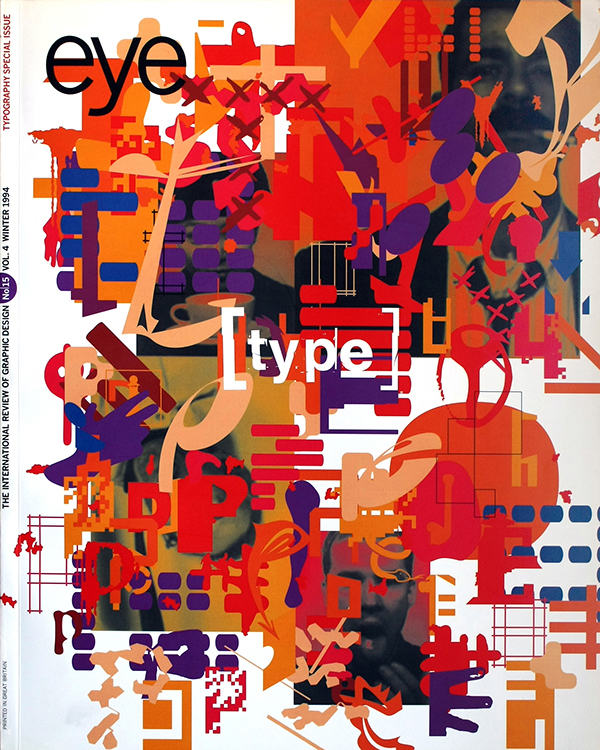

First published in Eye no. 15 vol. 4 1994

Michèle-Anne

Dauppe, lecturer,

Portsmouth University

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.