Tuesday, 12:10am

28 June 2016

Forging a new society

A New Childhood: Picture Books from Soviet Russia

House of Illustration, 2 Granary Square, King’s Cross, London N1C 4BH An exhibition of works from the Sasha Lurye Collection, 27 May–11 September 2016Children’s picturebooks from Soviet Russia. Clare Walters reviews A New Childhood at the House of Illustration

Anyone interested in Russian graphic design and illustration of the early twentieth century, or in the history of children’s picturebooks, will find the current exhibition at the House of Illustration fascinating, writes Clare Walters.

With works drawn from the collection of Sasha Lurye, it principally features picturebooks from Soviet Russia in the 1920s and 30s. However the show also includes examples of sumptuously produced children’s books made prior to the 1917 October Revolution, which were mainly aimed at a wealthy readership and focused on folk and fairy tales.

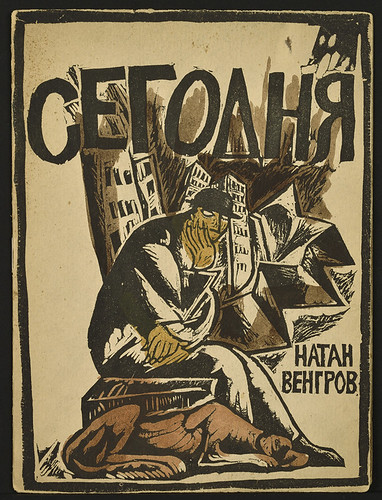

Cover illustration for Natan Vengrov’s Today (1918) by Vera Ermolaeva, founder of the first Soviet children’s publishing house, Segodnia, in 1918 in Petrograd.

Top: State poster (1925) by sisters Galina and Olga Chichagova. Russian folktale icons such as Baba Yaga and the Firebird are on the left, while Lenin shows the new literature on the right. The caption reads: ‘Out with the mysticism and fantasy of children’s books!! Give a new child’s book!! Work, battle, technology, nature – the new reality of childhood.’

Post-revolution, there was renewed focus on children’s publishing. As curator Olivia Ahmad explains in the catalogue A New Childhood (House of Illustration), a new form of children’s book was required that would ‘give practical instruction, instil socialist values and present a politically-endorsed vision of the future’. As early as 1918, the artist Vera Ermolaeva had founded the first Soviet children’s publishing house – Segodnia (Today) – in Petrograd, publishing limited editions of eight-page books. Due to war and a ban on private business, children’s publishing was slow at this time, but the ban was lifted in 1921 and by the following year there were more than 300 publishers in Moscow and Petrograd, as well as the state publisher Gosizdat. Almost 10,000 children’s books were published over the fifteen years following the Revolution, some in editions of up to 200,000.

Much of the work the publishers were producing was innovative and ahead of its time. The poet Kornei Chukovsky said, ‘The children’s author must, so to speak, think in pictures’ – and pictures are of key importance in these books, with many featuring high-quality illustrations, often in bold colour. But as well as illustration, the design of the books was taken seriously too, with an emphasis placed on interesting typography, and layouts where the text and images were integrated imaginatively.

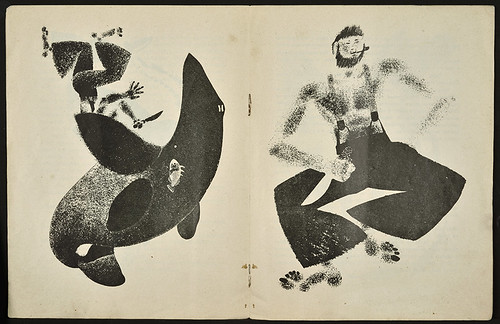

Eduard Krimmer’s illustrations for Rudyard Kipling’s How The Whale Got His Throat (1926). This vivid black image on a white background is buzzing with movement and energy.

Some publishers embraced new abstract forms. El Lissitzky’s About Two Squares: A Suprematist Tale in Six Constructions (1922) – where the black square represents the Suprematist movement and the red square communism – is a well-known example. But other lesser-known examples include Natan Altman’s illustrations for Nikolai Aseev’s poem Red Neck (1924), about a loyal Pioneer, which has figurative line drawings placed on top of sharp abstract shapes, and Eduard Krimmer’s work for Rudyard Kipling’s How The Whale Got His Throat (1926), which features graphic and dynamic black images on a white background.

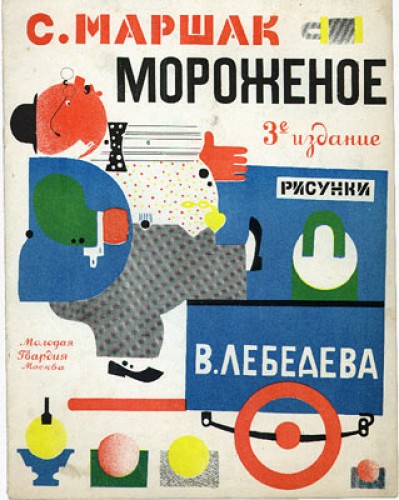

Formats were used imaginatively, too. Maria Siniakova’s illustrations for Circus (1929), also written by Nikolai Aseev, has pages that could be cut horizontally to mix and match the top and bottom halves of the performers. The illustrations were often very funny. Some were used to emphasise political points, as in Vladimir Lebedev’s depiction of the porky bourgeois capitalist stuffing himself with ice cream in Samuil Marshak’s Ice Cream (1925). Others are just witty in themselves. In Telephone (1926) by Kornei Chukovsky and Konstantin Rudakov, we see an enormous elephant incongruously holding a delicate candlestick phone to his ear. In The Jolly Alphabet (1926), we are shown a bird preening itself proudly. And in Mugs (1925) by Vladimir Komashevich, we discover a hilarious spread of boys’ faces laughing, crying, sticking their tongues out and even picking their noses.

Vladimir Lebedev, Ice Cream, 1925.

Some exhibits sent a shiver down my spine. In one case there is a small, very rare, title by Marc Chagall – his only children’s book – called A Story About a Rooster, The Little Kid (1917). While displayed on the walls are two tiny 91-year-old pencil-and-paper dummies of Vladimir Lebedev’s preliminary drawings for The Circus (1925) and The Hunt (1925).

Given the influence these early Russian children’s books had on publishing in Western Europe at the time – including Britain’s Noel Carrington, founder of Puffin Picture Books in 1940 (see ‘Puffins On The Plate’ in Eye 85) – it is well worth lingering over to discover more about the development of our own picturebooks. When you have finished seeing the exhibition, pop into the charming new Quentin Blake Gallery next door, which celebrates the work of the much-loved British illustrator – the founder of the House of Illustration.

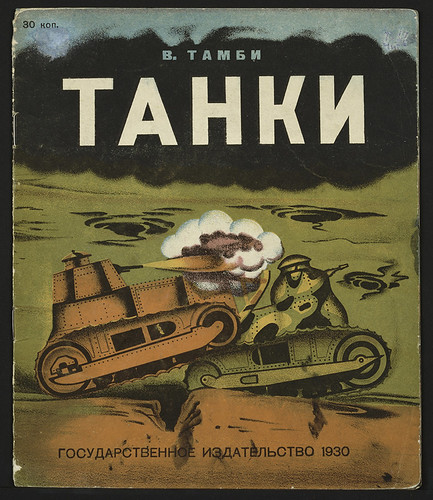

Tanks (1930) by Vladimir Tambi, one of many factual titles about the new Soviet State. A similar image featured on the cover of the first Picture Puffin book War on Land, discussed in James Russell’s article ‘Puffins on the plate’ in Eye 85.

‘A New Childhood: Picture Books from Soviet Russia’ continues at the House of Illustration, London until 11 September 2016.

Clare Walters, journalist, author of children’s picturebooks, London

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.