Summer 2007

Roadshows and rickshaws

Folk images help BBC World Service promote its 21st-century virtues to a rural Indian audience

A few years ago, an Indian restaurant group commissioned Bhajju Shyam, a young artist from central India working in the indigenous Gond folk tradition, to paint a mural for its latest London outlet. This was his first time abroad, on a plane, even in a city. Such pure culture shock left an indelible impression, which the Indian publisher Tara later helped him translate into book form. Shyam’s beautifully skewed vision of his visit, with Big Ben as a rooster and the Underground a giant earthworm, thus became The London Jungle Book, a distinctive bestiary that was to attract the attention of a marketing executive planning an advertising campaign for the bbc Hindi service in India.

This is a story about a happy collision of cultures; and the celebration, rather than exploitation, of native talent. It is, incidentally, an eye-opener for us in the uk, where we take the communications revolution for granted, and have entirely lost the ability to see the rooster in Big Ben.

Technology is largely absent, at best sporadic, in rural India (where 742 million of India’s one billion population live). Electrical supply is often limited to a couple of hours each evening, so newspapers are a major source of information. But low literacy rates mean that one person usually reads aloud to an assembled group. People are passionate about local and national politics; but they still love television when they can see it, especially quiz shows and Bollywood movies. Internet services, like mobile phones, are largely confined to urban areas; but even small towns have internet cafés, and travelling broadband vans are helping the rural community get online occasionally.

With less media choice, radio should therefore be a prime source of authoritative information from India and beyond. But in 2003, the bbc Hindi audience was in decline. Although BBC was still a major presence in India, it was primarily as a heritage brand; the young regarded it as something older people used. Those generations trust and even revere the BBC as the one constant reliable and objective voice, still broadcasting even through news blackouts imposed during past crises. But in general terms there was little understanding of exactly what the bbc is and does. The bulk of its Hindi audience lives in rural India, mostly in small towns in five northern states: Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh and Uttaranchal.

Pre-publicity rickshaw, 2004. Other direct media included book-bags, calendars, postcards and booklets.

Top: ‘Radio messenger bird’, from campaigns to promote the BBC World Service in rural India, 2004-2006. Art direction: Minus 9 Design. Illustration: Bhajju Shyam. Gond is a ritual and functional folk art style based in nature. Gond artist Shyam, from Patangarh, in Madhya Pradesh, portrays the bird with a radio dial eye and an antenna-like tail, carrying members of the BBC roadshow team on its back.

London calling

‘We needed to stem the decline in Hindi listening and find ways to connect and engage with the audience,’ says Jane Futrell, head of international marketing communications at BBC World Service. ‘But before we could do that, the service had to create new programmes. Once those were in place, we devised a brief around rural audiences.’

Futrell decided on a roadshow concept – something that the bbc had never attempted before in India – as a way of directly connecting famous radio voices with the people who listen. ‘Because we’re based in London,’ she says, ‘we needed an agency on the ground, used to rural marketing in India.

‘We knew the logistics would be difficult. My colleague Karen Yates and I toured Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, meeting people, seeing the villages and towns for ourselves. We wanted to bring live programme-making back from these areas. We wanted to send staff there. We needed vehicles, accommodation and access to technology.’

Linterland, a Bombay-based advertising agency specialising in rural initiatives, was chosen to organise a roadshow. ‘Voice of the People’, launched in February 2004, travelled to 44 rural locations and addressed about 140,000 Hindi-speakers.

The roadshow was extremely successful: people travelled hundreds of miles to attend events; and it gave programme-makers contacts and ideas for future on-air activity. Follow-up roadshows, which had fewer stars but more merchandise to give away, helped boost the broadcaster’s brand at the time of important state elections, and underlined the importance of that personal editorial involvement.

The brief for a visual campaign to support these roadshows stressed that the communication must ‘appeal to the individual in an unsophisticated, interactive manner’. In late 2004, Karen Yates, searching for an agency that could reflect rural Indian culture and tradition while exemplifying the qualities of a modern media brand, saw The London Jungle Book. She immediately contacted the book’s designer, Rathna Ramanathan, who runs Minus 9 Design, which operates in both India and in Reading in the UK.

Ramanathan had worked for a couple of years in advertising before setting up her own studio in Chennai (formerly Madras) in southern India, but rumours of an impending arranged marriage propelled her to Central St Martins and then the University of Reading to complete a PHD in publishing design. ‘I’d worked with Tara in India and was their only designer,’ she explains. The work was really interesting, not least because many of the books were completely hand-crafted – though not Shyam’s, which was printed by offset litho. ‘In the Indian context it’s sometimes more economical to screen-print than offset,’ she says. Within days Ramanathan had put together a pitch with Mariana Zegianini of Alan Bates Design; the following week she was in India, working up a design concept.

The initial communications were entirely visual: while literacy levels are low in rural India, the visual language of folk art is able to convey complex and subtle messages through narrative, metaphor and symbolism. Traditional methods of communication include wall paintings, tin plates on shops, stalls, rickshaws and street banners. The natural choice of artist was the now urbane Bhajju Shyam.

‘In India illustration in advertising has a slightly Western tinge, and is often purely comic,’ Ramanathan explains. ‘Our concepts were very generally defined; they were clarified only when I was in India working with the artist.’ The BBC paid Shyam London rates for his work: ‘It was most important that we were not exploiting his work, as some brands might,’ Ramanathan says. ‘We needed an interpretation of the message, not an appropriation.’ Shyam was able to finish building his house on the strength of this campaign.

Early concept sketch by Bhajju Shyam, 2004. In the ‘circle of life’, every important aspect of rural life is depicted: education; sport (cricket); festivals (music and dancing); work (sowing and harvesting); the BBC radio interviewer; and the influence of technology (aeroplanes and computers). At the bottom of the circle an earnest discussion takes place among the men seated in the village square. Elements of this were worked up into greater detail and used in t-shirts, wall paintings and billboards.

Local and global

There were several contexts and potential contradictions to consider: the history between Britain and India; the fact that this was an international brand communicating with an Indian people quite isolated from the modern world. The communication had to converse with this audience in a way that was specifically appropriate to them while still true to the bbc brand. Equally important was managing the process. The brief was conceived, designed and signed off in London; but it was produced in India using local talent from different language and cultural backgrounds. Commissions went to a silkscreen printer from Perungudi, a t-shirt printer from Coimbatore, an offset printer from Chennai, hand-made paper from Pondicherry, a Gond artist from Bhopal and a cinema artist from Chennai. The policy was to source all materials locally, and everything was printed in India and sent to the Hindi heartland by road.

But nothing is straightforward in India. ‘The printer has broadband so I send images, he scans them, sends them to me; we worked really fast,’ Ramanathan says. ‘But it slows down when he has to get the hand-made paper; monsoon rains are not entirely appropriate for paper-making. So we had to buy cheap hairdryers to dry the paper. We sent everything by road from southern India right up to the north, and the truck would get stuck at state borders. You’d have to get someone to drive out to see what was happening. All these different levels of technology – that’s very Indian, for me. At the same time it’s still much quicker to get my mobile fixed there.’

Over four campaigns to date, Ramanathan has incorporated other visual styles. Theertham Balaji, a physicist who is also a celebrated Kalamkari artist, created a variety of illustration concepts using this traditional story-telling art form to convey an entirely contemporary narrative of interaction between the BBC team and audience. In parallel with this (fourth) campaign a contemporary artform, still uniquely Indian, was employed: cinema posters. Athiveerapandian, based in Chennai, was commissioned to create Bollywood-style portraits of well known BBC presenters. Each stage of the campaign used a mix of different media appropriate to the target audience: folk media such as wall paintings and tin plates; direct media such as t-shirts, leaflets, souvenir cards, postcards, calendars, book bags; and mass media such as billboards and newspaper ads. One of the most popular initiatives was a calendar featuring positive images of rural Indian faces, again a highly unusual concept in Indian advertising. ‘These things have a very long life,’ says Ramanathan. ‘In the West we simply throw them away, but in rural India they cut the pictures out and use them on the wall.’

Marketing lessons

The net result is that the BBC has increased its Hindi audience in India from 10.2m in 2003 to 17.1m in 2006. The four campaigns have been a success at every level. Programme-makers have a better understanding of their rural listeners and are making more suitable programmes for the ambitious and information-hungry people they met. The marketing department has learnt valuable lessons about addressing rural audiences who, through globalisation, are now ‘pretty media-savvy’, Futrell says. ‘We’ve helped our colleagues turn around a declining audience and discover new audiences who are helping to re-invigorate programme-making. Our next challenge is to maintain this momentum in rural areas while looking at our Indian audiences in the urban ones.’

Ramanathan found some lines by English academic A. H. R. Fairchild that she felt especially relevant to the bbc’s importance in India at a time of rapid change: ‘The most distinctive mark of a cultured mind is … to put one’s self in another’s place, and see life and its problems from a point of view different from one’s own.’

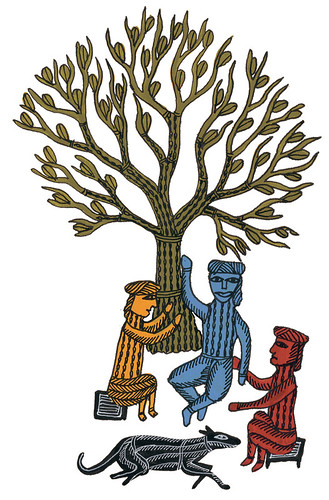

Village men by Bhajju Shyam, 2005. ‘It was important not to assume that “progress” meant that only in a urban setting,’ says Rathna Ramanathan. Villagers are shown in conversation, to reinforce the idea that they can contribute to the growth of the country.

Steven Hare, freelance journalist, author, Wiltshire, UK

First published in Eye no.64 vol.16 2007

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.