Friday, 12:01am

31 July 2015

Cold War culture-jammer

Hispanic photomonteur Josep Renau aimed Technicolor jets of scorn at the mirage of US consumerist culture. By Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for eyemagazine.com.

In 1939, after the end of the Spanish Civil War, Josep Renau moved to Mexico and began a life of exile. He was a highly successful artist and designer, an accomplished maker of posters and photomontages, a former Director General of Fine Arts in the Ministry of Public Education and Fine Arts, and a member of the Spanish Communist Party. During his years of banishment in Mexico, he began work on a series of photomontages fiercely critical of the United States. In 1967, a selection of the images titled Fata Morgana USA: The American Way of Life – a ‘fata morgana’ is a mirage – was published in East Germany (the German Democratic Republic), where he resettled in 1958.

Renau (1907-82) has never been as familiar to English-speaking viewers as his achievements deserve and only in recent years has his work received close historical attention in Spanish exhibitions and monographs – it was 1976 before he returned to Spain as a visitor. The American Way of Life was exhibited last year in Madrid and ‘Tristes Armas’ (Woeful Weapons), an exhibition pairing his anti-war images with the photomontages of Martha Rosler, has just closed at the Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, home of Renau’s archive.

The images shown here come from an expanded edition of Fata Morgana USA, with additional montages and text in Spanish and English, published in 1991 to coincide with an exhibition at the Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego. As a piece of print, the book looks dated now, with over-glossy paper and prosaic typography, but the pages are large and Renau’s montages go off like jumbo firecrackers. If John Heartfield’s furious pictures for Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung set the black-and-white template for political photomontage – Renau admired and wrote about Heartfield – then the Spanish photomonteur’s colour-soaked culture jams are an advertising-influenced, Hollywoodised upgrade, years before Adbusters. When Heartfield saw Renau’s work in Berlin in the 1960s, he didn’t approve, but the chromatic excess reflects a new media reality.

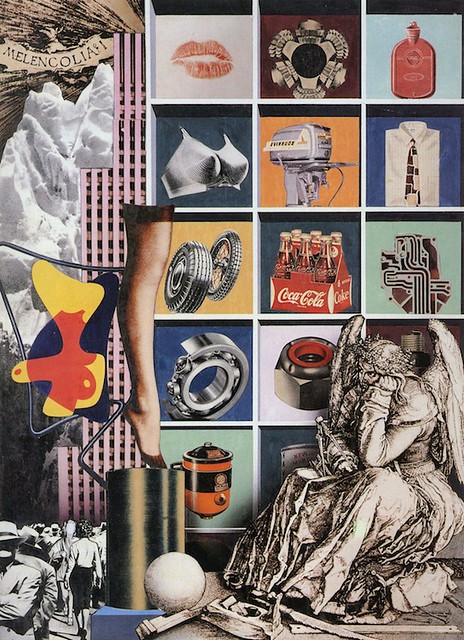

Photogenic Melancholy, photomontage, 1955.

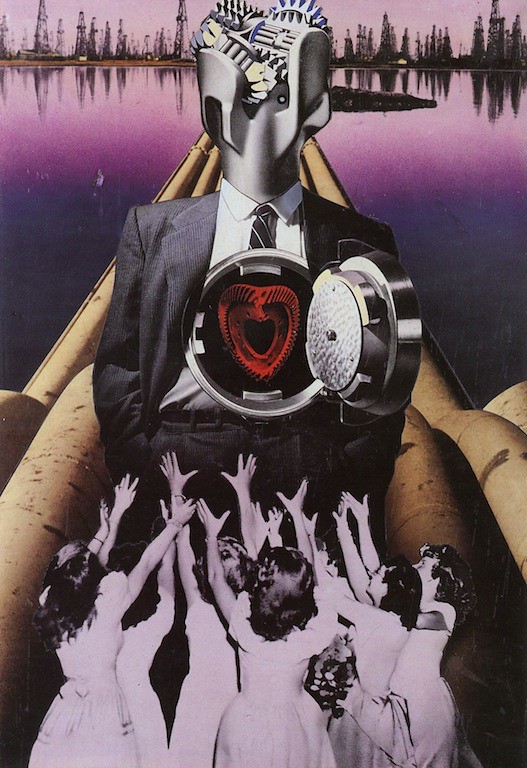

Top: The Fascinating Oil King, photomontage, 1957.

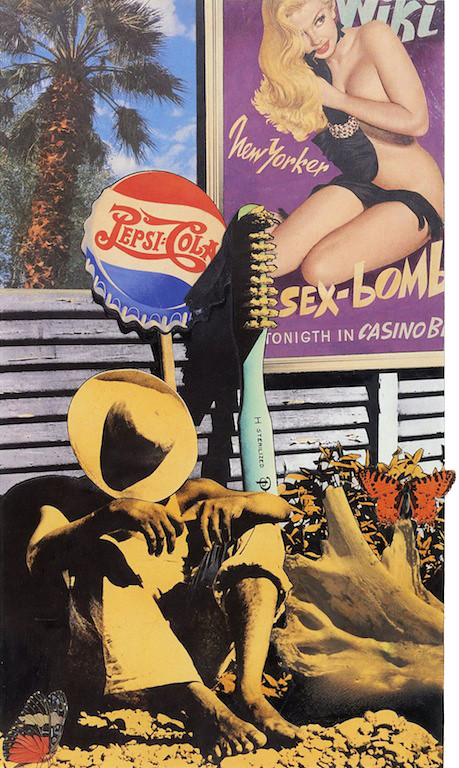

Renau made the photomontages in the 1950s and 1960s and the series originally consisted of 200; there are 69 in the book. The earlier pieces seem especially prescient now, anticipating the iconography, collaging strategies and collisions of ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture in both 1960s Pop and the postmodern art of the 1980s and 1990s. Renau recolours images, plays havoc with their scale and devises bizarre juxtapositions. Photogenic Melancholy (1955), placed near the end, treats the nascent imagery of Pop – lips, car tyres, Coca-Cola bottles and a bra – as cause for gloomy introspection, borrowing the brooding angel from Albrecht Dürer’s mysterious engraving Melancholia (1514).

In other satirical montages, Renau scatters images of chorus girls, a self-help manual, crime magazines (a regular source of pictures: Renau despised them), juicy rashers of bacon and film stars such as Marilyn Monroe. His printed sources included Look, Fortune, National Geographic and Life, from which he also took cuttings of articles for use in the book.

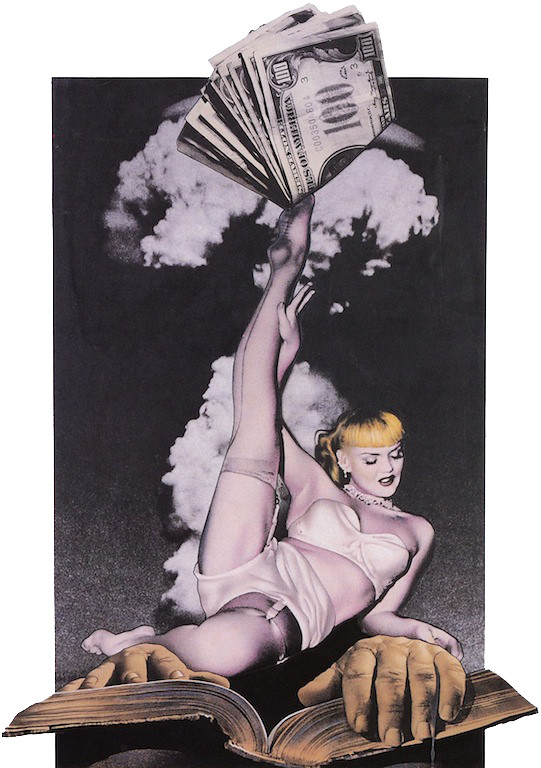

Balance, photomontage, 1959.

Fata Morgana USA is organised as a sequence of self-contained spreads, each given its own title, with the main photomontage occupying the right-hand page. On the left, Renau deposits other visual material – photographs, unmodified source pictures and related photomontages – and short texts that lend ironic support to his theme. These include extracts from the poem ‘The People, Yes’ by Carl Sandburg and The Power Elite (1956) by the sociologist C. Wright Mills, and an extraordinary passage, titled ‘Confessions of a Racketeer’, where a US general describes, in 1935, how he made Mexico, Haiti, Cuba and other countries safe for American business interests (‘I might have given Al Capone a few hints.’)

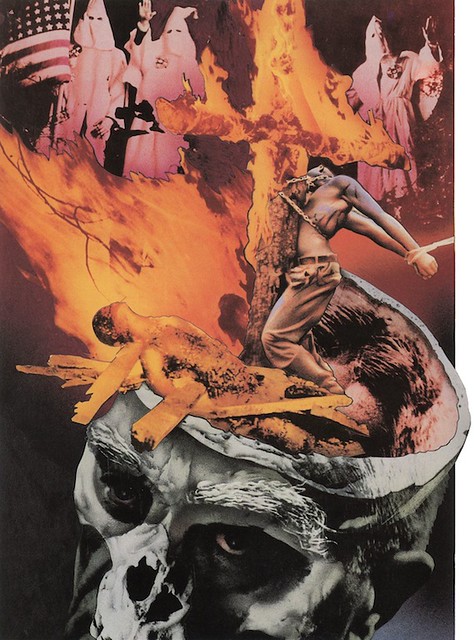

Racial Orgasm, photomontage, 1951.

Renau’s sense of outrage was sharpened by years of living across the border in America’s underdog neighbour, a country where, as he notes in a statement at the end, ‘the physical, psychological and political pressure of Yankee imperialism is expressed more directly and brutally than elsewhere’. In these excoriating image-splices, Renau directs Technicolor jets of scorn at American capitalism, the country’s history of murderous racism, its financial exploitation of women’s bodies, reliance on capital punishment, and military arrogance. He castigates the entertainment industry, seeing the monopolistic mass media as agents of ‘propagandistic mystification’ softening up American society.

‘The author would consider it a high acknowledgement of his work,’ Renau concludes, ‘if the reader would discover for himself the perverse and inhumane in the confused, brilliant and “fascinating” signs of the “way of life”, which enslaves to a larger or smaller extent hundreds of millions of people inside and outside the United States. This is the sole aim of this book.’

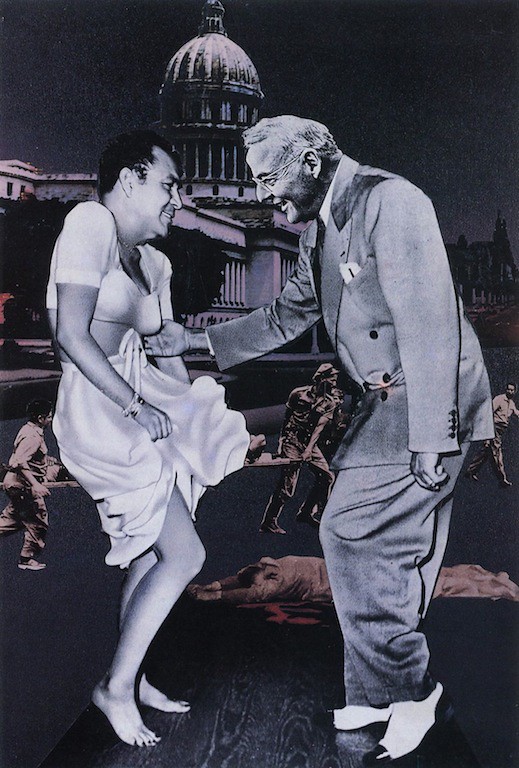

Hot Rumba (Foster Dulles-Batista), photomontage, 1956.

It takes an effort today to see these images as they might have struck viewers in their time. Their broader targets have become highly familiar since the 1960s, though that doesn’t make them mistaken or invalid, while much of the imagery has inevitably dated. Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista and John Foster Dulles, Republican Secretary of State in the 1950s, seen cosying up to each other against a backdrop of mayhem in Hot Rumba (1956), require an explanatory note today. If at times Renau seems to labour the point and even to verge on hyperbole and hysteria, that might be a sign that we are a little too inured to the causes for anxiety – now globalised anxieties – that he identifies with legitimate alarm. Saturated by colour as we are, his colour cannot look quite as scathingly hyper-real as it did 50 years ago, yet it still pervades many of these scenes like a toxic mist.

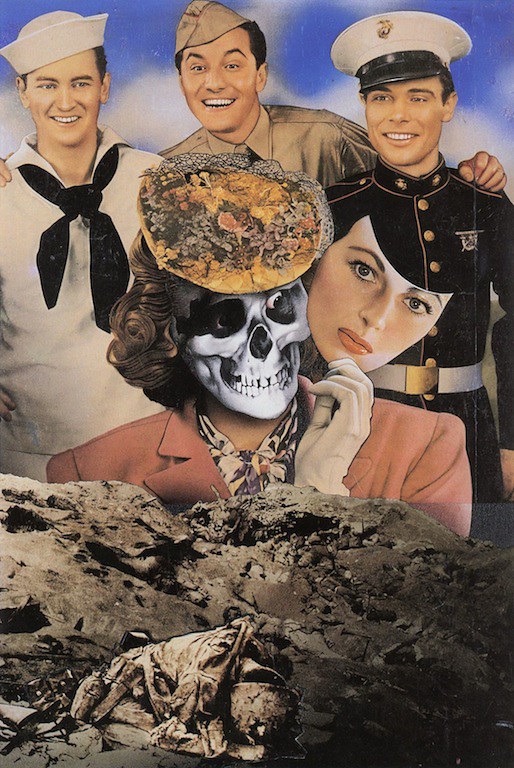

Oh, This Wonderful War!, photomontage, 1957.

Tropical Poem, photomontage, 1960.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, London

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue.