Winter 1994

An advocate of the public good

Dan Friedman: Radical Modernism

Dan Friedman Yale University Press, £40.00, $65.00 Reviewed by Emily KingIn the past twenty years Dan Friedman has re-invented himself. Having worked as a successful mainstream corporate designer in the mid-1970s, he now chooses to hover on the border between art and design. Depending on how you define that boundary, his objects, installations and images could be placed on either side. Friedman has claimed variously that he is trying to break down, cloud over, question and explore the divide between the disciplines. Reading this book, you sometimes get the feeling that for him, the most important distinction is one of lifestyle. Why be a designer when it is artists who have all the fun?

The title Radical Modernism seems to promise some kind of treatise. The text on the book’s jacket describes its contents as a ‘meditation on behalf of “radical modernism”’ and suggests that the images of Friedman’s work that appear within are intended to illustrate his ideas. Friedman certainly feels he has something to say about Modernism and its continuing relevance, but among the lavish illustrations, his message is liable to get lost. Rather than embellishing his ideas with images of his work, he appears instead to be justifying his work with a series of theoretical ponderings.

Possibly aware of this danger, Friedman has placed the essay ‘What is Wrong with Modernism?’, the book’s central theoretical thrust, over a spread in the middle of the book. Starkly unillustrated, these words beg to be read. After cantering through the history of Modernism, from its idealistic roots to its co-option by corporate America and subsequent loss of moral authority, Friedman proposes ‘radical modernism,’ which he defines as ‘a reconsideration of how modernism can embrace its heritage along with the new reality of our cultural pastiche, while acknowledging the importance of a more humanistic purpose.’ ‘Radical modernism,’ he suggests, ‘acknowledges our existing culture, conventions and history contrasted with a creative spirit to question and reconceptualize.’

Friedman’s approach has something in common with other attempts to salvage the notion of modernity. Jürgen Habermas, in his essay ‘Modernism – An Incomplete Project,’ argues that the Modernist’s aim must be to forge a new connection between modern culture and real life, taking our ‘vital heritages’ into account. But Habermas is pessimistic. He believes this new link can only be established when the forces that modernise society, such as industry and marketing, are steered in a different direction and concludes that the chances of this happening are not good.

Friedman is an optimist. He believes we can combat a culture ‘dominated by corporate, marketing and institutional values’ by expressing ‘personal, spiritual and domestic values’ in our work. In the final essay of the book, Friedman sets out his ‘radically modern agenda.’ He urges us to ‘embrace the richness of all cultures,’ to think of our output as ‘a significant element in the context of a more important transcendental purpose’ and to ‘live and work with passion and responsibility.’ The emphasis is placed firmly on the individual and his or her arrival at some kind of spiritual and cultural awareness. Friedman insists that we should ‘become advocates of the public good,’ yet we are given no real idea of what he believes this amounts to. Apart from a little recycling, we are left with the idea that all might be saved through the attainment of a heightened spiritual consciousness.

This book may or may not offer a broadly applicable escape route from our postmodern / late-modern dilemmas, but whatever its title might suggest, that is not what it is about. In the end, what Radical Modernism amounts to is a retrospective of Friedman’s work since the early 1970s. Friedman addresses different areas of his output in a number of essays which appear under momentous titles such as ‘Design and Culture’ and ‘Truth and Beauty.’ By favouring this approach above the chronological, he implies that his development over the past 25 years has been fashionably organic rather than straightforwardly linear. According to Steven Holt, ‘design visionary’ at Frogdesign, Friedman has not pursued a career but has been conducting an experiment. In his essay ‘Model Revolutionary,’ Holt suggests that Friedman has spent the last few years ‘exploring, exploding and evolving himself.’ Friedman does not take trips to India, he goes on ‘spiritual journeys.’

Radical Modernism offers the chance to look over the range of Friedman’s design and artwork. As Jeffrey Ditch suggest in his essay ‘Hip Hop Modernism,’ Friedman has certainly escaped a signature style. Tables playfully sporting grass skirts appear in the same pages as Citibank’s authoritative corporate identity. Several spreads from the catalogues Cultural Geometry, Artificial Nature, and Post Human are reproduced – powerful graphic work widely agreed to have outshone the exhibitions it accompanied. These teasingly provocative, deadpan images arguably provide the most interesting discussion of contemporary culture within the book.

Friedman’s smooth bald head appears on the cover of Radical Modernism and other portraits of him are scattered throughout. Like Alfred Hitchcock with his portly profile, Friedman uses his own distinctive image to stamp his identity on the project. These portraits alongside the many pictures of his home, confirm that the subject of the book is Friedman himself. Do not buy this book hoping to resolve the problems facing modernity in the late twentieth century, but it because you are a fan.

Emily King, design historian, London

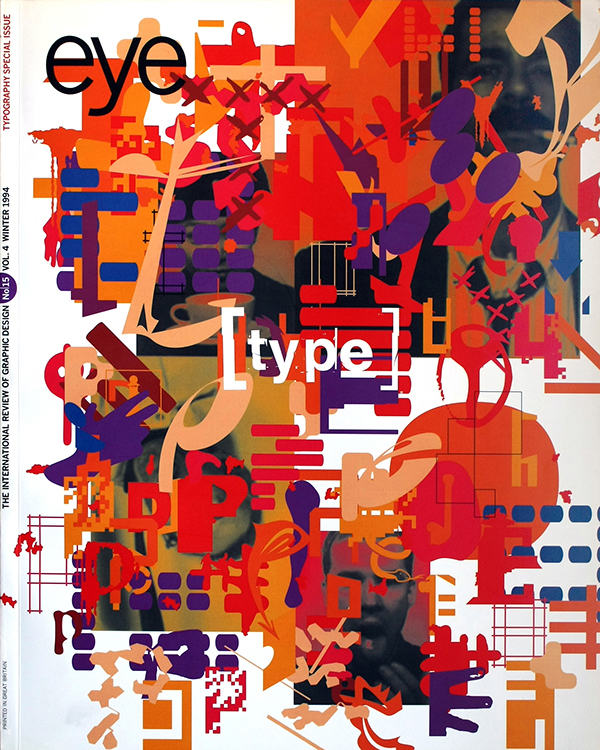

First published in Eye no. 15 vol. 4 1994

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.