Summer 2010

Cartographical display

Magnificent Maps

British Library, London, 30 April–19 September 2010, Reviewed by Max RobertsThings were not simple for a pre-nineteenth-century map, which might have to show off the capabilities of its artist, impress a patron, intimidate a rival, subjugate a population, validate a claim, or indoctrinate the members of a classroom. Very occasionally, someone might use one to find their way.

‘Magnificent Maps: Power, Propaganda and Art’, showcases 80 maps and globes, mainly from the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, up until the 1940s. These are display maps, intended to be hung on walls to impress, and perhaps convey a message, rather than be privately studied. All of them are intricate and some are spectacular. There is plenty of rich symbolism to interpret. Every map has its own evocative story to tell, whether celebrating a defining moment in history, or revisiting a skirmish between long-forgotten monarchs of long-disappeared states. Domains range from the entire heavens, to maps of the world, continents, countries, states, counties, cities and country estates. Designers are almost as varied: artists, monks, seafarers, travellers, military surveyors, professional illustrators, satirists and graphic designers. People who like to study maps, marvelling at their beauty and detail, and also their place in history, will not be disappointed. However, the exhibition’s low lighting may make seeing the details difficult for some.

The challenge with such an exhibition is how to organise the material, and here this is roughly by the location in which a map would have been displayed. Starting at the Palace, we first visit the Gallery (where guests would be impressed and intimidated by the maps), the Audience Chamber (where visitors would be impressed and overawed), the Bedchamber (maps extolling the spiritual virtues of the occupant), and the Cabinet of Curiosities (where the intellectual accomplishments represented by the prized possessions might reflect on the owner). Away from the Palace, in the Street, maps might act as propaganda or simply decorate, but in the Merchant’s House they could be marks of allegiance or status symbols. In the Secretary of State’s office, maps would be essential for administrative purposes, but an artfully constructed one might sway a decision. Over at the Schoolroom, a young captive audience could be ripe for early indoctrination by colourful wall displays.

Above and beyond the material speaking for itself there is not really a coherent story to take away. This exhibition is enormously successful as a means to allow and encourage the general public to see a wide range of rare, accomplished and attractive maps. However, it is not about the development of cartographical techniques or map symbolism, nor does it show the evolution of propaganda techniques. There is no sense of the development of the professions of cartographer or graphic designer, nor how breakthroughs in printing techniques influenced design techniques. The complete lack of chronological organisation means that people interested in these topics will be frustrated. However, because this exhibition and its selection of material is clearly not intended to tell any of these stories, this lack of organisation means that there is little risk of implying spurious trends in design.

As to the actual message of the exhibition, display maps existed and apparently were designed to impress, influence or intimidate, but for the most part we do not find out whether they were successful.

The highlights include a map of Savoy (1704) whose miscalculating Duke had been defeated and exiled by the French. Issued by the French, the map, entitled L’Etat du Duc de Savoie, is presented underneath a portrait of King Louis XIV. In the Audience Chamber, an intricate tapestry, the Sheldon Map of Oxfordshire (1663), shows how much and yet how little England has changed. A map of The Settled Part of Pennsylvania (1687) names 700 people who purchased plots of land. What became of these pioneers? Over in the Street, the octopus gets a particularly bad press, being likened to Russia (1877), Prussia (1917) and Churchill (1942). An easy cliché, but who would be today’s octopus? In the Schoolroom, Cruchley’s Map of Europe (1851) is refreshingly free of obvious attempts at indoctrination. The borders and countries may be hopelessly out of date, of interest to historians only, but among the details we find contour lines marking northern limits of the growth of palms, vine, oak, barley and pines. With today’s environmental concerns, benchmarks against which climate change can be assessed are topical and important. Yes, maps can be created and used for political ends, but let us not lose sight of their other uses, too, even as display.

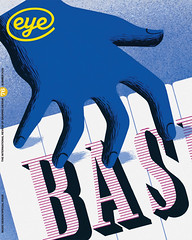

First published in Eye no. 76 vol. 19 2010

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.