Autumn 2019

Encyclopedic ambitions

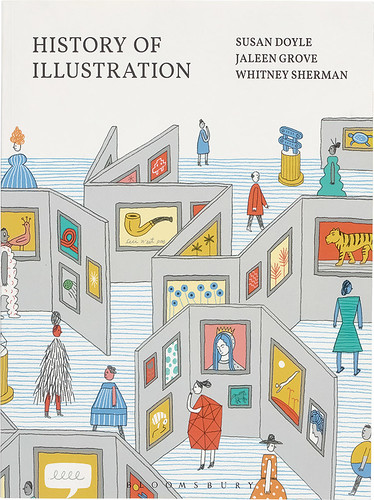

History of Illustration

Edited by Susan Doyle, Jaleen Grove, and Whitney Sherman. Fairchild Books, £171 (hardback), £64.80 (paperback)

English-language historical surveys of illustration have been undertaken on both sides of the Atlantic from the nineteenth century onwards. For all their virtues many have suffered from similar faults: parochial focus, exaggerated emphasis on biography, dissociation from cultural and textual settings, and especially in US entries, a tendency to slide into narratives of style. For far too long ‘the history of illustration’ has been poorly theorised, anecdotal and clubby.

Editor Susan Doyle and associate editors Jaleen Grove and Whitney Sherman have delivered something genuinely newsworthy: a true survey with encyclopedic aims, stretching from prehistory to the digital present.

English-language historical surveys of illustration have been undertaken on both sides of the Atlantic from the nineteenth century onwards. For all their virtues many have suffered from similar faults: parochial focus, exaggerated emphasis on biography, dissociation from cultural and textual settings, and especially in US entries, a tendency to slide into narratives of style. For far too long ‘the history of illustration’ has been poorly theorised, anecdotal and clubby.

Cover of History of Illustration. Cover design by Brian Rea and Pablo Delcan.

Top. Copperplate engraving by Odoardo Fialetti (1573-1638) of the ‘gravid uterus’ in De formato foetu by Spiegel and Casseri, 1626.

Editor Susan Doyle and associate editors Jaleen Grove and Whitney Sherman have delivered something genuinely newsworthy: a true survey with encyclopedic aims, stretching from prehistory to the digital present. Primarily Western in focus but global in reach, buttressed with substantial historical and scholarly context, this generously illustrated 500-page book has become the likely undergraduate course text for the history of illustration in North America, and a significant entry in the UK. (Disclosure: I contributed a short essay, but the project is so huge that my review is unencumbered by this small contribution.)

History

of Illustration (HOI)

breaks new ground in several respects. First, the editors labour to

extend the book’s reach beyond Europe and North America, having

recruited experts and commissioned chapters on illustrative

traditions for India, China, Japan, Latin America, and the Muslim

world. There are conceptual challenges to be managed. A fourteen-page

chapter devoted to sub-Saharan Africa runs from prehistory to the

early 2000s. Chapter author Bolaji Campbell confines his efforts to

the narrative production of the Yoruba, primarily associated with

Nigeria – a representative choice difficult to evaluate for a

general reader. I have admired Yoruba relief carved doors in museums,

and the text presents that appealing form as ‘illustrative art’,

gamely eliding the challenge of strict categories. However generously

reasoned and necessarily abbreviated, these chapters go beyond

gestures of inclusion and represent serious efforts to expand our

view. They add visual and factual substance to the book, but

especially they point to vast zones of cultural production, both

historical and geographical, which await the curious student beyond

this text.

Second,

wherever possible the editors and contributors make choices to

include the work of notable women, in the process almost inevitably

squeezing out famous men. An example: in Chapter 20, in a spread on

American pin-up illustration, three images are reproduced – an

Indian maiden by Adelaide Hiebel; a work by Rolf Armstrong, a

mainstay of calendar publishers Brown and Bigelow; and a showcard by

Zoë Mozert. Hiebel is somewhat obscure; Armstrong is well

known; and Mozert has recently been excavated. Meanwhile Gil Elvgren,

the most celebrated of 1950s pin-up painters, is mentioned but does

not appear in reproduction. In this negotiated settlement, is

anything lost by leaning into the cultural complexity of women

painting women for (largely) male consumption? No. Plenty is gained.

Elvgren can take care of himself.

Larger questions are at stake. Canons are built over time from choices on choices. Author A’s judgments about who matters are likely to be repeated by Author B a decade later, and so on. The gender imbalance of the historical record is not neutral. Very few women show up in canonical chronicles, but not because they were not working: in addition to some who broke ground in editorial and advertising work (the few who appear in early twentieth-century histories), many others worked in markets considered less serious or even invisible (e.g., children’s books and educational publishing, respectively). The story was always gendered; rebalancing is not a distortion, but a correction. What matters is not the hoary claim of ‘greatness’ attached to canonical figures in the clubby manner I alluded to above, but investment in the cultural tissue of modernity – what viewers and readers have imbibed through industrial print.

A more inclusive view of the past is badly needed in today’s art and design schools. Women comprise a majority of our students. They require a past that includes them.

Third, sensitive to the weaknesses

associated with stories of style, deference to markets, and the cult

of professionalism, HOI

comes with a packed lunch, as it were, of intellectual and historical

context, tucked into the folds of the book. These 58 numbered

insertions or ‘theme boxes’ supply scholarly summaries of

subjects (e.g., semiotics, orientalism, the panopticon) by writers of

note (Saussure, Pierce, Said, Foucault) along with bibliographies.

This reading supplement comprises a significant element of the book.

The

arrival of History of

Illustration is a signal

event. Its scale and density may overwhelm some. I am reminded

of a lesson I learn every time I design a new course. Always I am

tempted to ask: What

must I cover? Soon afterward,

confounded, I return to the proper question: What

do I want the students to learn?

The first question is about me; the second, about them. While HOI

is rigorously pedagogical, I will probably use it as a supplement,

rather than a spine. Above all, I will ask students to buy the

paperback to serve as a compact reference library.

A

question hangs over the book, and to a certain degree ‘illustration

studies’: should illustration be essentialised or historicised? The

opening chapters of HOI

suggest the former view: ‘Illustrative traditions’ point to

universality. Except in the most generalised contexts, I subscribe to

the latter, which is that narrative picture-making and illustration

are not

the same thing; illustration is a modern phenomenon inextricably tied

up with new forms of reading and emergent consumer culture, including

advertising. Most cultural historians tend toward such views. (I have

argued elsewhere that ‘illustration’ might not really have

a history, but rather participate in the story of complex

cultural enterprises, like periodical publishing.) Both perspectives are represented within HOI.

Practitioners are most likely to essentialise illustration. They do so because in an under-theorised field many have ached to feel part of some tradition largely denied them by art history and high visual culture. At heart, HOI was written for beginning practitioners. Its preface concludes: ‘Most of all, the student will gain a sense of belonging to a tradition and a field with ancient roots and inestimable social impact.’ Ultimately, the book delivers admirably on that promise.

D. B. Dowd Professor of Art and American Culture Studies at Washington University, St Louis

First published in Eye no. 99 vol. 25, 2019

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.