Autumn 2023

How the alphabet became

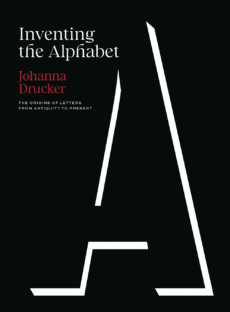

Inventing the Alphabet: The Origins of Letters from Antiquity to the Present

By Johanna Drucker, Design: Rae Ganci Hammers, University of Chicago Press, $40, £32

The current obsession with font design has stimulated the field like nothing else in recent memory. Dating back to the introduction of tools such as Fontographer and Freehand a generation ago, a shifting of the process – from the difficult translation of hand drawing into the cutting and forging of hard metals to a purely digital one – accounts for the near mania of contemporary font production. It appears that there are a zillion ways to render the letters ‘A’ through to ‘Z’: and everyone is too busy doing that to wonder about the origins of those letters that appear to be infinitely malleable.

Johanna Drucker’s Inventing the Alphabet goes way back in deep time to explore ideas about where the alphabet came from. Drucker has not really written a history of the alphabet; instead, she has created a history of the history of the alphabet, stemming from her particular fascination with the ways that generations of scholars (using the term loosely here) have struggled to understand the origins of this most foundational of human inventions. It is not a straightforward story of accumulated knowledge but a convoluted tale of fantasising, conjecture and theorising that does eventually turn into a more coherent evolution of thinking on the subject as standards of study, citation, and the use of archeological evidence eventually give shape to the narrative of how letters came to represent sounds of speech.

Alphabetic writing seemed so miraculous that early theorists credited the Almighty with inventing the alphabet. Kabbalistic theory said that the letters were in the constellations; or that God gave them to Adam, who passed them to his son; or God put them on the tablets given to Moses – leading to the obvious question: how could anyone read any of this? And this was after the Greek historian Herodotus had already posited (in the fourth century BCE) that the alphabet had come to the Greeks via a system that Phoenician (Cadmean) traders in Asia Minor used for accounting. He referred to the Greeks modifying the letters, recognising that the forms could morph as they responded to language in use.

Drucker relays and expands this narrative (the result of 40 years of her own research) as a story of the development of knowledge, that by necessity was framed by the means that her predecessors had access to in order to understand history in their own times. So much early work on the issue of the divine origins of letters was done without any artefactual evidence, simply relying on written accounts. Fascinatingly, the development of diplomatics (the concern with the legitimacy or authenticity of documents) was a moment that finally liberated the inquiry away from the divine. But this happened only after generations of writers, starting in the Middle Ages, began to create manuscripts (that were then copied, with greater or lesser degrees of accuracy or citation) to explore the history and development of the alphabet as not only a conveyor of Classical knowledge, but of the vernaculars. Simultaneously a lot of creativity seems to have gone into the invention of fictional ‘angel’ or ‘magical’ alphabets, and the appearance (and re-appearance) of those graphical fakes took decades to be eliminated finally from the serious study of languages. However, the appearance of such idiosyncrasies also provides a map of the transmission of knowledge, as one can see which copyist was using what earlier document to create their newer version.

As universities started forming across Europe in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the study of ancient or obscure languages became part of scholarly practice: printed later, polyglot bibles are evidence of this interest in comparative letters and what they might reveal about the origins of communication. Inventing the Alphabet provides numerous fascinating illustrations of compendia (cross-comparisons of letters from different languages) and ‘script charts’ as scholars attempted to use the letters themselves to compile their own evidence of the relationships of letterforms across languages and time.

Cover by Rae Ganci Hammers.

Top. Facsimile of an engraving originally published by Willem Goeree, Utrecht, 1700, shown in the sixth chapter of Johanna Drucker’s Inventing the Alphabet, ‘The Rhetoric of Tables and the Harmony of Alphabets’.

More recognisably modern practices of research based on the translation and study of inscriptions and, finally, archeological evidence appear, and shift the entire field of study away from untethered speculation to firmer territory. Comparisons of real artefacts and inscriptions established that the alphabet was a human invention that had developed over time and which reflected geographic and cultural specificities. Spoiler alert: Herodotus was not that far off! The current consensus is that the alphabet can be attributed to Semitic-speaking peoples of the Levant, spreading across Egypt, the Sinai Peninsula and the Fertile Crescent. The distribution of the alphabet as a system for writing expanded with Mediterranean trade. The spread of the alphabet took about 2000 years, but more research keeps pushing the dates backward as archeological evidence is continuously being deciphered by patient and intrepid historians.

But empirical evidence does not prevent misinterpretation. In the chapter ‘Alphabet Effects and the Politics of Script’ Drucker explores the ways that historians (starting in the mid-nineteenth century but continuing through to the 1970s) tried to minimise the Semitic role in the alphabet’s development in favour of a crackpot theory of the superiority of an Aryan / Greek lineage. The barely veiled racism of this romanticisation of a Classical past has been countermanded by less biased scholars, but it just shows that there is no field of human endeavour not subject to prejudice and politics. It is hard not to imagine that the process of the creation of knowledge (and its pitfalls) that Drucker explores is mirrored in ‘the history of the history’ of other fields. But Drucker – who is an artist and typographer in her own right – has given us an amazing, obsessive piece of scholarship to remind us that our alphabet is ‘a major component of human systems’ with implications that radically transcend the actual forms of the letters themselves.

Lorraine Wild, designer, writer, teacher at CalArts, Los Angeles

Buy ‘Inventing Alphabet’ at the Eye magazine bookshop

See ‘Words made flesh’ in Eye 18

First published in Eye no. 105 vol. 27, 2023

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.