Summer 2010

Information overlord

Beautiful Evidence

Edward Tufte lecture, Royal Geographic Society, London, 19 May 2010Anticipation was high among the audience for this rare public appearance by Edward Tufte in London. What could we expect from a lecture by a man described by The New York Times as ‘the Leonardo da Vinci of data’? Would we see classic Tufte; envisioning Tufte; quantative Tufte; ‘flatlands’ Tufte; ‘space-lands’ Tufte; sparklines Tufte? Art Tufte or science Tufte? Would he touch all the bases and be generalist Tufte? Or specialist Tufte? Would we see Tufte the person or – as signalled by the title of his lecture – Tufte reciting from the most recent of his four influential books? The latter was most likely and that is what we got.

The evening’s talk was structured around his ‘Principles of Analytical Design’ (published in Beautiful Evidence) and illustrated by Charles Joseph Minard’s ‘anti-war’ poster, which demonstrates Napoleon’s disastrous march to and retreat from Moscow of 1812.

Tufte’s principles are as follows:

1) Show comparisons which aid contextual understanding particularly when seen mapped and scaled one to another. Showing ‘the evidence of the eye’ liberates us from ‘wordy arguments’ to ‘visible certainty’. The contrasts between the numbers that started out on Napoleon’s ill-fated mission and those who returned are graphically shocking.

2) Show causality. Minard’s map does not just show the ‘location of bad news’ but, through a temperature chart, how people were dying as a result of a bitterly cold winter.

3) Show multivariant data. The ‘world is rich’ with data and we should show the inherent complexity of information. Minard showed scale, location, direction, dates and temperature.

4) Integrate word and image. ‘Evidence is evidence’, whether in words, images or numbers, and too often these components of information become segregated. Some designers continue a convention once imposed by technological constraints, by emphasising the aesthetic qualities of composition above the communication of content. Tufte quotes Eric Gill: ‘if you look after truth and goodness, beauty looks after herself.’

5) Demonstrate credibility. Consider why anyone should believe or trust you. Credible information has detail (what, who, when and where?). Providing documentation and sources (e.g. URLs) is the minimum level quality control for the audience.

6) Show the relevance, quality and integrity of the content. Content matters, so get the best evidence you can and always strive to get better content.

7) Show evidence adjacent in space. This is a new principle introduced since the publication of Beautiful Evidence. Seeing one thing next to another allows easier comparisons to be made than when presented stacked one on top of each other. It also avoids having to make additional references and keys.

In recent Web-based projects Tufte has specified that 91 per cent of the screen should be content. He suggests we should ‘trust optical capacity’ and blows out the ‘seven choice myth’ in which it is thought seven is the maximum number of things the eye / brain can cope with at any one time. He tells us that The New York Times has 400 links on its homepage and has 10m visitors daily.

Tufte concluded by introducing us to the notion of data-words or sparklines. These are word-size trend graphs. Those familiar with the conventions of sparklines would be able to ‘read’ at a glance a substantial amount of information in the space of an average size word. Tufte’s innovation has limitations but he defends this by stating they are ‘approximately right and not exactly wrong’.

A short question and answer session allowed Tufte to reflect on the notoriety aroused by his criticism of PowerPoint presentations, which, he suggests, reduce sentences with verbs and nouns – the perfect form of communication – to inarticulate ‘grunts’ of bullet points threatening the integrity of the original message. For those in the information communication business this is something of a contentious issue based on the view that we have less time to read and therefore require information chunked into bite-size pieces.

As for the future, Tufte sees the development of physical, gesture-based interfaces where you can ‘feel the data’, giving a literally hands-on experience of information as a meaningful interaction with content.

The audience spilled out onto the pavements of South Kensington arguing about the viability of sparklines or why Tufte did not talk more about his recent sculptural work, dissecting his performance compared with his intellectual peers. But weeks later we are still talking, emailing, texting and communicating about the event.

First published in Eye no. 76 vol. 19 2010

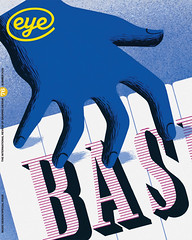

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.