Winter 2016

Living in the present

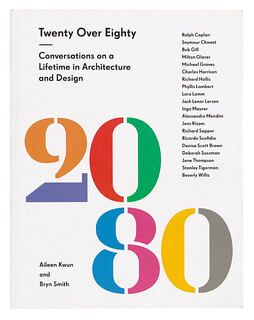

Twenty Over Eighty: Conversations on a Lifetime in Architecture and Design

By Aileen Kwun and Bryn Smith<br> Princeton Architectural Press, $35, £21.99<br> Designed by Paul Wagner<br>

You want inspiration? Buy this book! It is as simple as that. Cleverly exploring a demographic that is too often sidelined, Aileen Kwun and Bryn Smith asked twenty giants in the fields of design and architecture about the wisdom they have acquired during their eight or more decades on the planet. The vivid and quotable insights from one interview alone could fill this entire review.

These are people who have been devoted to their work, which is inseparable from their lives. Whether they work in textiles, furniture, graphics, illustration or architecture, their age unshackles them from being polite or politic. It starts with the 91-year-old writer and educator Ralph Caplan, who came to design via a humour magazine, and finishes with 88-year-old architectural planner and all-round mover and shaker Beverly Willis, who in 2009 wrote and directed her first film – about women architects – at the age of 80.

The authors set out this elegantly designed book as a series of conversations, some face to face, some via email exchanges. As young design writers, their worry was that it would be impossible to ‘capture the essence of twenty legends … for a conversation worth their time, and yours’. However, with astute questioning and careful editing, they turn the varied responses into a satisfyingly fluent and coherent read.

The project is timely, not to put too fine a point on it. Here’s a chance to catch up with people who were influential at one time, but who have somewhat fallen off the radar. The late architect Michael Graves, left partially paralysed by illness, tries to ‘redesign the healthcare experience … from the unique viewpoint of a patient’. He is splenetic about firms who work in that field but make no attempt to understand what it’s like to be in a wheelchair: ‘What they’re doing is making interiors, like a hotel. Interiors,’ he says scathingly.

Or the riveting story of Charles Harrison: from postwar US Army cartographer to the first African-American executive at Sears, designing thousands of user-friendly products, including the moulded plastic garbage bin that likely sits outside your house – essentially identical to the one invented by Harrison in 1966.

Milton Glaser is, as always, outrageously quotable: ‘Nobody tells you you’re an artist. “I’m an artist.” There it is and nobody can take it away from you. Isn’t it remarkable? You couldn’t do that if you were a brain surgeon.’ ‘I believe that art and design is like sex and love. They are fine independently … and every once in a while you get both at once. But not often.’ ‘My essential mantra in professional life is: do no harm. Which is very complicated …’

There’s also much about the centrality of good teaching, in classroom or studio. Here’s Bob Gill: ‘These people in my class haven’t originated anything, they’ve been told what to do. So the first thing I tell them is, “I will hate everything you do, but I love you, so that’ll make it easier.” And I really do like them, and I really do hate everything they ever do.’ The brilliant Denise Scott Brown, one of the authors of Learning from Las Vegas, insists that what designers and architects ‘really badly need is a School for Clients!’

Phyllis Lambert, who in 1954 lobbied her father, Samuel Bronfman, to hire Mies van der Rohe to design the Seagram building (sending him an eight-page, single-spaced screed) is asked, ‘When did you first become curious about art and architecture?’ She replies, ‘As a child. Children are pretty smart; they don’t go around with nothing in their heads.’

In this foreword, the art director Michael Carabetta writes that the interviewees ‘prove Newton’s Law – a body in motion tends to stay in motion. There’s little that surprises them. They’ve seen it all, or enough to know what makes the world tick. That’s knowledge. And once they have that knowledge, they learn there is always more to learn.’ A common thread running through the book is of looking forward to ‘the next job’, of not looking back or resting on their laurels.

Ricardo Scofidio (81), whose recent projects include the overhaul of Lincoln Center in New York in 2013 and the creation of that city’s High Line, says that for him, ‘the most difficult thing has been to live in the present, and to resist thinking about what the future will look like.’

Much of their work still seems, if not futuristic, then relatively untouched by time. Kettles, lights, buildings, logos, posters, theories and more – if you want to know what twenty lifetimes of excellent work in the visual / spatial field looks like, and what those lifetimes have taught the practitioners, this book is for you.

Cover from Twenty Over Eighty.

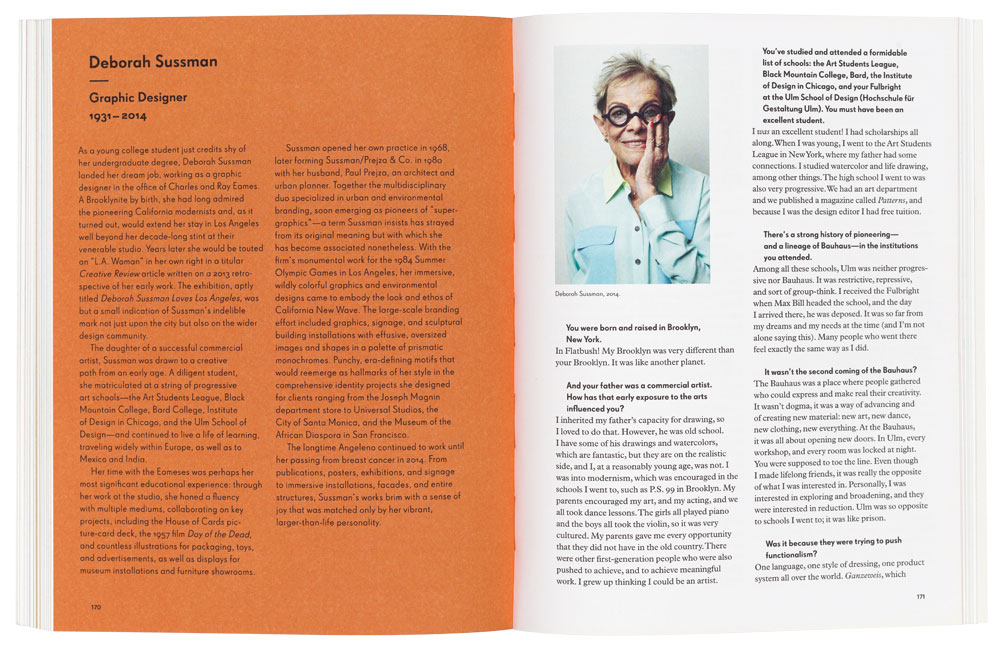

Top: Spread showing a conversation with Californian designer Deborah Sussman.

Martin Colyer, freelance art director, writer, London

First published in Eye no. 93 vol. 24, 2017

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 93 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.