Summer 2022

Printer poet

The Last Cuckoo: Dennis Gould

Directed and produced by Mark Chaudoir, edited by Ben Bishop and Polly Ward, camera by Richard Jopson.Poet and letterpress printer Dennis Gould in his Stroud workshop.

Stroud-based poet, letterpress printer and activist Dennis Gould is the subject of The Last Cuckoo, a short film that captures the life and work of an individual within the creative environment that sustains him. Filmed when Gould was 79 (he is 85 this year), the pandemic interrupted director Mark Chaudoir’s original schedule, but his study has managed to capture the essence of someone fully committed to poetry and to print.

In The Last Cuckoo, Gould’s words, whether spoken out loud or printed on paper, are framed against the backdrop of the Cotswold town that has played an important role in fuelling his rebellious spirit. Gould’s involvement in activism has been there since his earliest days of political protests and CND marches. As a young man in the peace movement, he even spent a short time in prison for blockading an Essex airbase. Later, he joined the staff of Peace News.

As a place with its own history of counterculture, Stroud has since cultivated both Gould’s art and his activism. He is filmed in his workshop among an array of books, prints, old photographs, protest badges, maps, woodblock letters and type cases – an assemblage of memories, beliefs and tools. Gould stresses how he came to letterpress from the ‘content’ side of things, as a writer, rather than working as a printer first. If any editing or revising takes place, he explains, it is done as he hand-sets his type. Gould is unique, Chaudoir says, because he is ‘a poet who prints his own words’.

Originally from Burton-on-Trent in Staffordshire and brought up in Derbyshire, Gould arrived in Gloucestershire in 1989 and began working in letterpress in 1991. (Prior to this, while he had designed cards and posters himself, he left the print side of things to other professionals.) Following workshops with John Grice of the Evergreen Press, Gould acquired a press himself and began setting his own work. His first was one of his own poems, the fourteen-line ‘Stroud Eyeview Blues’, which he set in 10- and 12-point Times New Roman.

Since then Gould has written, printed and self-published his own poetry, following a long tradition that includes Blake, Shelley and Whitman. As Gould acquired more sets of type, or parts of sets, his work developed an imperfect style of its own, unlike the ‘fine’ printing undertaken by Grice. Through necessity, Gould has said, his prints mixed letters from different alphabets, creating a trademark mishmash of words across a variety of media. At one point in the film, Gould sports a bright orange T-shirt emblazoned with his own ‘We are all migrants’ lettering. He also favours old maps as canvases, perhaps maintaining some connection to the map-making work he carried out during his time in Cyprus in the 1950s with the Royal Engineers, where he also organised football matches.

Chaudoir’s background in graphic design – and his extensive career at the BBC and as a commercials director – no doubt influences the various animated sequences. Inky, print-block textures feature in one section, while in another, motion graphics bring a dynamism to Gould’s poetic homage to the cafes of Stroud and their imagined clientele. A sombre flow of black-and-white images also offers a poignant moment in tandem with the rhythm of the poet’s voice. The music, by Sarah Llewellyn and Hannah Barnett, provides a joyous background of jazz brass and tumbling Dixieland, performed by Barnett, The Tonal Ensemble and the Giffords Circus Band.

If Gould’s work links further back to the days of pamphleteering and self-produced political tracts, The Last Cuckoo is not solely about this aspect of his life. It takes pleasure in having him recount some of the passions that inspire his poetry, namely cycling (that ‘two-wheeled gypsy queen of the highways and byways’), football and the blues. His ‘Birthday Blues’ poem sums up his position today: ‘Still believing in the art of anarchy, the craft of poetry and the gift economy.’

In this way, this lovingly crafted sixteen-minute film becomes a deeper biography of an artist who sees himself very much embedded within the pleasures of life, not detached from it as a mere observer. Gould’s poetry, still connecting with readers through a jumble of printed letters, is a celebration of that.

Mark Sinclair senior editor at Unit Editions and freelance writer, Stroud

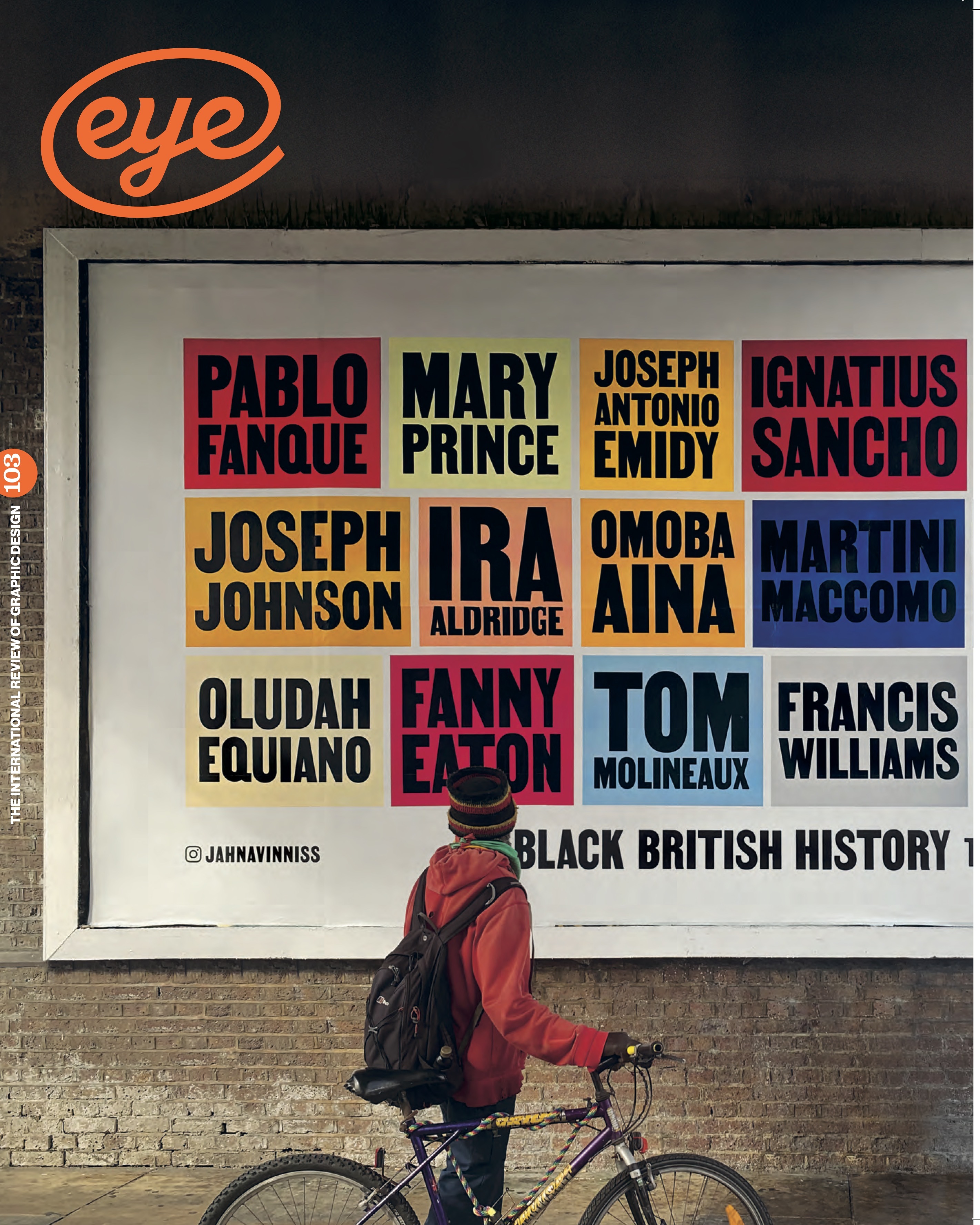

First published in Eye no. 103 vol. 26, 2022

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.