Autumn 2021

Shaded tints, a view of US racism

The Design of Race: How Visual Culture Shapes America

By Peter Claver Fine. Bloomsbury Visual Arts, £65 hb, £19.99 pb

The Design of Race arrives at an inflection point in American society. Awareness of racial, socio-economic and class disparities has been at the forefront of national politics, culture, academia and media. The Black Lives Matter movement arose in reaction to numerous cases of white police officers killing unarmed Black men. BLM has been paralleled by ‘critical race theory’, an emergent lens for examining whiteness and power. Universities and corporations are rapidly embracing diversity, inclusion and equity initiatives as the United States grapples with a legacy of slavery, racially discriminatory Jim Crow laws, the partially fulfilled gains of the civil rights movement of the 1960s, and the growth of today’s white supremacist groups.

The book presents a landscape of visual works that make a strong case for learning about the racist history that American Blacks have endured through graphic imagery. The Design of Race is written with passion and erudition about a topic Fine has embraced since his graduate studies at Arizona State University, and he demonstrates this commitment by using a few illustrations from his MFA thesis project.

The book might have benefited from a better subtitle, defining ‘design’ as graphic design (inclusive of advertising, packaging, typography and branding), and ‘race’ as largely African-American descendants of slaves. The cover of the paperback version – in contrasting black and a painterly whitewash – communicates Fine’s position: racial injustice is a polarised issue. He argues that Blacks have been systemically diminished and ridiculed through visual communications.

The methodologies of Fine’s book include description, analysis and opinion. He does close readings of graphic artefacts with an art historian’s attention to details of rendering, material, reproduction media, use of design elements and principles, and the work’s historical context. As most of the graphic works he examines are from the late nineteenth to the mid twentieth centuries, The Design of Race is more a history than an assessment of current racialised depictions.

Most of his contemporary examples and source citations stop in the 1990s.

Hybridity, exceptions and nuance do not serve Fine’s rhetorical position in The Design of Race. For example, the man who modelled for the Rastus character, Cream of Wheat cereal’s ‘racial avatar,’ was Frank L. White, a professional chef at a Chicago restaurant, who apparently took pride in this representation. Nike’s Air Jordan logo is depicted in one piece, and Fine frequently mentions the commodification of Black bodies, but the reader does not learn that Michael Jordan earned $1.3 billion, as estimated by Forbes, from Nike’s corporate endorsement.

An additional story of using a racialised portrait that deserves telling in The Design of Race is that of Betty Crocker’s face, used by General Mills to brand baking products, and which for decades was that of a white, blue-eyed, slightly patrician, middle-aged woman. In 1996 the company morphed 75 diverse faces into the new Betty, who is now brown-eyed and smiling warmly. ‘She … [has] facial accents that could be interpreted as Caucasian, Hispanic, Asian or Native American,’ says the Chicago Tribune. Fine focuses on racialised packaging personas Aunt Jemima, Cream of Wheat’s Rastus and Uncle Ben – all three brands dropped their characters in the light of 2020’s BLM protests.

One derogatory example that Fine mentions is a plastic figurine of former US president Barack Obama, which he found in a shop in rural Colorado. Compare the impact of this crude product, however, with Shepard Fairey’s Obama poster, which depicted a heroic and aspirational view of the same person, and which was instrumental in attracting younger voters to what became a two-term presidency. Inclusion of the Hope poster in the book could have opened a dialogue about saviour complex; appropriation; and precedent and influence.

Fine devotes a significant portion of his text and two-thirds of the images in the coloured plates to the work of established Black fine artists. The works of Glenn Ligon, Carrie Mae Weems, Michael Ray Charles, Hank Willis Thomas and Kara Walker show the expressive creativity of artists interrogating race in America. While this art might be visually and conceptually refreshing to the design community, the gallery and museum context removes it from the quotidian environment of much graphic design. Ligon sold his white-on-white painting Untitled (I Was Somebody) through Sotheby’s auction house for $3,973,000 – certainly impressive, but well beyond much of design’s populist and functional experience.

The letterpress-printed, activist broadsides of Amos Kennedy, the designs of Black Panther Minister of Culture Emory Douglas, and W. E. B. Du Bois’s seminal data visualisations might have presented a more varied, relevant and inspirational view of Black graphic design. Inclusion of contemporary work addressing race in America, like the Black Lives Matter street mural in Washington, as sanctioned by Mayor Muriel Bowser, would bring Fine’s book to the present moment.

The Design of Race has sections on print, photography and film media. Lithographers Currier and Ives are rightly given pointed criticism for the Darktown Comics print series, and Herb Lubalin is lauded for his ‘subversive’ use of black-and-white photography to depict a Black Santa for an Ebony magazine Christmas ad. Fine provides an amusing interpretation of television’s The Andy Griffith Show, where the cast performed stereotypical Black tropes in ‘whiteface’. But what of ‘colourism’ within Black films, whereby darker leading men are often paired with lighter partners?

The book is a worthy contribution to a critical history of racialised images and texts in advertising, art and design. Exploring the grey areas, the paradoxes and complexities of race in America would add depth to Fine’s book, and including more contemporary graphic design and less fine art would make The Design of Race an essential text in many design history courses and required reading by enlightened practitioners.

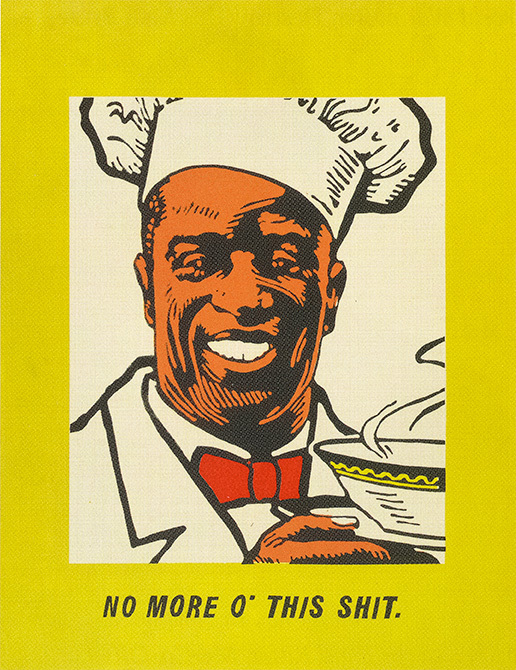

Cover of The Design of Race: How Visual Culture Shapes America. Top. Screenprint by Rupert García, 1969. Courtesy of the Artist and Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco, CA.

Steven McCarthy, professor emeritus, University of Minnesota

First published in Eye no. 102 vol. 26, 2021

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.