Spring 1992

Reputations: Neville Brody

‘People are using the computer in a very rigid, pseudo-religious way and we are trying to say that the technology is simply a tool of communication and should be treated as organically as any other tool.’

Neville Brody was born in London in 1957. He attended the London College of Printing from 1976-79 before becoming a freelance designer, mainly of record sleeves. In 1981 he became designer of The Face magazine, where his typographic experiments won international acclaim. He went on to art direct Arena, Per Lui (Italy) and Actuel (France). A book of his collected designs, The Graphic Language of Neville Brody, was published in 1988 to coincide with a retrospective at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum. He is an enthusiastic advocate of computer-based design and in 1991 helped to launch Fuse, a disk-based ‘interactive’ magazine of new typefaces.

Rick Poynor: It is almost four years since your book and the exhibition at the V&A and during that time you have kept a much lower profile than in the preceding period. Has this been a conscious decision on your part?

Neville Brody: After the exhibition a number of things happened, the most significant of which was that we completely stopped getting any British work. At the moment we have one UK client. The other important thing that happened was that in the late 1980s, at the time of the exhibition, design was booming, but had run out of ideas and reached the point where you didn’t even need a fully formed idea, just the beginnings of an idea, to have to put into print. It was swallowed up immediately and before it could be developed it was everywhere, then it was gone. This voracious animal was consuming itself. The third factor at that point was over-exposure. People were writing me off the week after they been saying “you should see the guy’s work.” I just felt that it was time to go invisible again.

RP: Were you aware of envy or resentment from other designers?

NB: Certainly. It came out in the press. There were a lot of reviews and usually the ones from other designers were maliciously critical for no constructive reasons. All I could assume was that it was some form of bitterness and had nothing to do with evaluating the work itself. As a result I felt even more closed off from the rest of the design industry.

RP: Looking back, do you think in terms of your development as a designer that it was good or bad, helpful or unhelpful, to have been celebrated so early?

NB: Malcolm Garrett has said that he thought it was too early. I still don’t think so. As far as I’m concerned, I come in to work, put in a very long day, go home with a takeaway, and that’s it – I just get on with the work. So to be quite honest all that publicity and press didn’t affect me. I simply felt it was the right time to put on that kind of show. If it hadn’t been me, it would have been someone else. It was an attempt to create a catalyst for design. There was a lot happening and the book and the show were supposed to be a way of focusing thought. It wasn’t intended to be a Neville Brody celebration at all.

RP: Would you say that you have been misunderstood?

NB: People in design seem to think that it was to do with self-publicity. The point is that what I’ve tried to do is nothing to do with self. It is always to do with the thinking procedure behind design and the point of the book was that people had seen the design and I wanted them to consider ideas. In Britain, most of the reviews said “great book, but why do you need the text?” But we found that in other countries, certainly in America and Germany, people liked the text. Abroad, I had debates with people about ideas in the book; in Britain the discussion was focused on my personality. So in many ways, at least in Britain, the show and the book misfired.

RP: Your move from The Face to Arena was well timed. Why did you finally give up art directing Arena?

NB: For a number of reasons. Arena, for me, became the focus of what was happening in Thatcherite Britain. I felt that the magazine had become very much a shopping catalogue and I didn’t want to spend my time working on a magazine that was going to show different pairs of socks. I’m not going to be over-critical because I still know them and their heart is in the right place, but as an independent magazine free from the restraints of a major publisher Arena was in a position to promote discussion and go out on a wing, to take risks in its views. And it didn’t.

RP: With the move to Arena came an unexpected switch to simple Helvetica headlines, but over the last four years the world has caught up. The sans serif look is everywhere from TV graphics to annual reports. It’s become another style.

NB: On Arena I wanted to reject style and decoration and show that it is actually the design that counts. We were trying to force Helvetica, which I hated, to be emotional. It was also an ironic statement. For years ago, everything was over-designed; design was the content. At Arena we were saying, well, no, the content is the content. In the end, though, it failed.

RP: So what comes next? You can’t go back to style graphics and the retreat into minimalism by your own admission hasn’t worked.

NB: I think that your question itself is part of the problem – the view that things have to “come next” is the wrong way to look at design. Something has gone wrong in the last ten to twenty years. People have come to believe that design is about fashion and it’s not. I’m looking for work which has a very emotive, expressive quality, regardless of choice of typeface or typographic style, which is just the surface effect. Over the last two years, we’ve been going through a process of stripping away stylistic connotations. If anything stylistic has crept into the output of anyone working with me, I’ve told them to do it again. There are hundreds of different ways to work which are all modern and to concentrate on one is a mistake.

RP: What are you trying to achieve with Fuse, the digital magazine you launched with Jon Wozencroft?

NB: The essential purpose of Fuse is to try to demystify digital technology. People are using the computer in a very rigid, pseudo-religious way and we are trying to say that the technology is simply a tool of communication and should be treated as organically as any other tool. The keyboard itself is like a painter’s palette or a musical instrument and we feel that in the future the computer will be treated far more seriously as an artistic medium, as a way of getting back to expression and emotion. We’re trying to use the computer to break down preconceptions about what typography should be. The other side of it is that typefaces tend to take about two years to publish with a major company. We wanted a magazine in the form of a digital medium that could be changed every issue: the “story” is the typeface and in each issue you get four ‘features’, or typefaces.

RP: What sort of interaction are you trying to promote? How do you intend people to use the Fuse material?

NB: We intend people to abuse Fuse material! I don’t expect people to use the typefaces in commercial situations, though it’s their choice, of course. I do expect that people will look at what we’re doing and then do something themselves, or try to change what we’ve done. We’re actually getting results sent back to us which we hope to publish in a future issue – Fuse refused, if you like, or defused.

We’re also going to produce an issue using what we call “freeform typography”, in which the “type” itself is no longer an alphabet and is much closer to the idea of the keyboard as a musical instrument on which you compose creative pieces. Type has a certain rhythm, it has colouring, it has repeats, and you respond emotionally to the visual aspect of a test as much as to the language it embodies. We’re trying to extract the visual character from the written word. You won’t be able to compose readable words with these freeform typefaces, but you will be able to compose visual structures which you have inherent in them the basic rhythm and visual quality of type. We’re trying to create a form of visual poetry.

RP: Is your own contribution to Fuse – State – to be viewed as a stage on this journey into typographic abstraction?

NB: State was deliberately kept readable. I wanted to take it much further, but after discussion with Jon Wozencroft, we decided that it would be a half-way stage, still retaining the underlying form of the alphabet.

RP: You seem to be talking about a kind of painting with type. Are you in fact a frustrated painter?

NB: No, I’m not, because in many ways I am a painter. I will never be a painter using traditional brushes and paint, but I am a painter using digital technology.

RP: When you talk about a typeface that has no linguistic content, that is simply a collection of organised marks, you appear to yearn for some idea state where there is no message apart from the emotion you embody in the marks. Do you ever feel that the content gets in the way of the design?

NB: No, part of what we are trying to do is point out that all typographic communication has this other level – that it’s communicating more than just words on paper.

RP: But isn’t that the first thing any student of typography learns?

NB: Yes, but it becomes unthinking. In the age of communication we are living in now, when more is being communicated by more people than ever before, we want to isolate it, to draw it out, to use it as a way of communicating emotionally. It may or may not have reverberations back to the written word.

RP: So what kind of applications would such a “typeface” have and where would we encounter it, apart from in a publication like Fuse?

NB: I don’t know where it could manifest itself. At the moment I’m obsessed with electronic communication and mixing together what we do here with type with the process of digital publication. You can publish a magazine as a multimedia file on a disk and this is undoubtedly the future. There is still a place for printed work, but I think we have only just begun to explore the potential of electronic media.

RP: Your early work with the Macintosh had an obvious “Mac” look to it. Do you feel you’ve now reached a point of fluency with the computer where you are the master and the machine has become transparent?

NB: Absolutely. I even remember the night it happened. It was 11.30 and I had been sitting attacking the machine. I suddenly realised that I was in control and there had been a definite switchover.

If you are going to use a computer you have to really struggle with it, otherwise it will make all the decisions for you. The default mechanism means that if you don’t specify the angle of a line, it will draw a straight vertical line. If you don’t select a typeface, it will select one for you. I see so many Macintosh gimmicks in a designer’s work.

RP: You once said on television that if we were going to be entirely honest in our communications we would only ever use one universal typeface. Yet you go on designing typefaces. Why do we need more typefaces?

NB: Well, we don’t and we do. The reasons why we are producing so many typefaces at the moment is to try and break the mystique of typography. When I said we only ever need one typeface this was ironic, because at the time I said it most designers were relying on the choice of typeface as the solution to the design problem.

In fact, I think in the future everyone will have their own typeface, which is healthy. With computers that respond to handwriting, the digital medium will be personalised. Typefaces will be released like records with very limited shelf lives.

RP: Isn’t the danger of all this that we are going to enter a typographic Babel? The whole idea of Modernism and the clarity it preached was the concentrate attention on the message itself rather than the means of its delivery.

NB: I feel very strongly about this. There are two sides to Modernism, one of which I wholly support, which is that modern communications should be humanistic, expressive and benefit the people. The side I don’t adhere to is the fascistic one that dictates and expects everyone to conform. I will do anything to support individual means of expression and if this means there are a million typefaces, I’ll support that, because I think people should have as much choice as possible. If the choice doesn’t exist, people should be allowed to make their own. The ability to design typefaces on the Macintosh is a true revolution. It will terrify ardent Modernists, but we’re moving into a new kind of modernism – the modernism of the individual, where the individual has access to the means of communication. It means that design is no longer a kind of temple. Everyone should be taught how to communicate visually.

RP: What about the idea being explored by some of the Americans and maybe yourself to some extent that a typeface design should be as subjective as possible? Designers like Jeffery Keedy and Barry Deck allow entirely personal factors to determine their designs.

NB: All language is personal and that, to me, justifies very personal typefaces. It’s a mistake to think that graphic design should be anonymous or impersonal. So I fully support what Keedy and Deck are doing.

It’s interesting the way that attention has shifted from the page to the font. People are investing typeface designs with the intensity they once brought to the page.

RP: There can’t be many designers in London who are sustaining a business largely on the strength of foreign assignments.

NB: If it wasn’t for the foreign assignments, we would be bankrupt for sure. Ninety-nine per cent of our turnover is international. We’ve designed stamps for the Dutch post office. We’re doing the signage for the new National Gallery of Germany in Bonn. We are redesigning national Austrian broadcasting – two TV channels and four radio channels. We’re just about to do two jobs in Brazil. So for me it’s the most exciting time we’ve ever had, because we are dealing with different people with different views all the time. We find that people abroad are able to cut through the personality side much more. We have respect from other designers, architects and clients, because they know what we think.

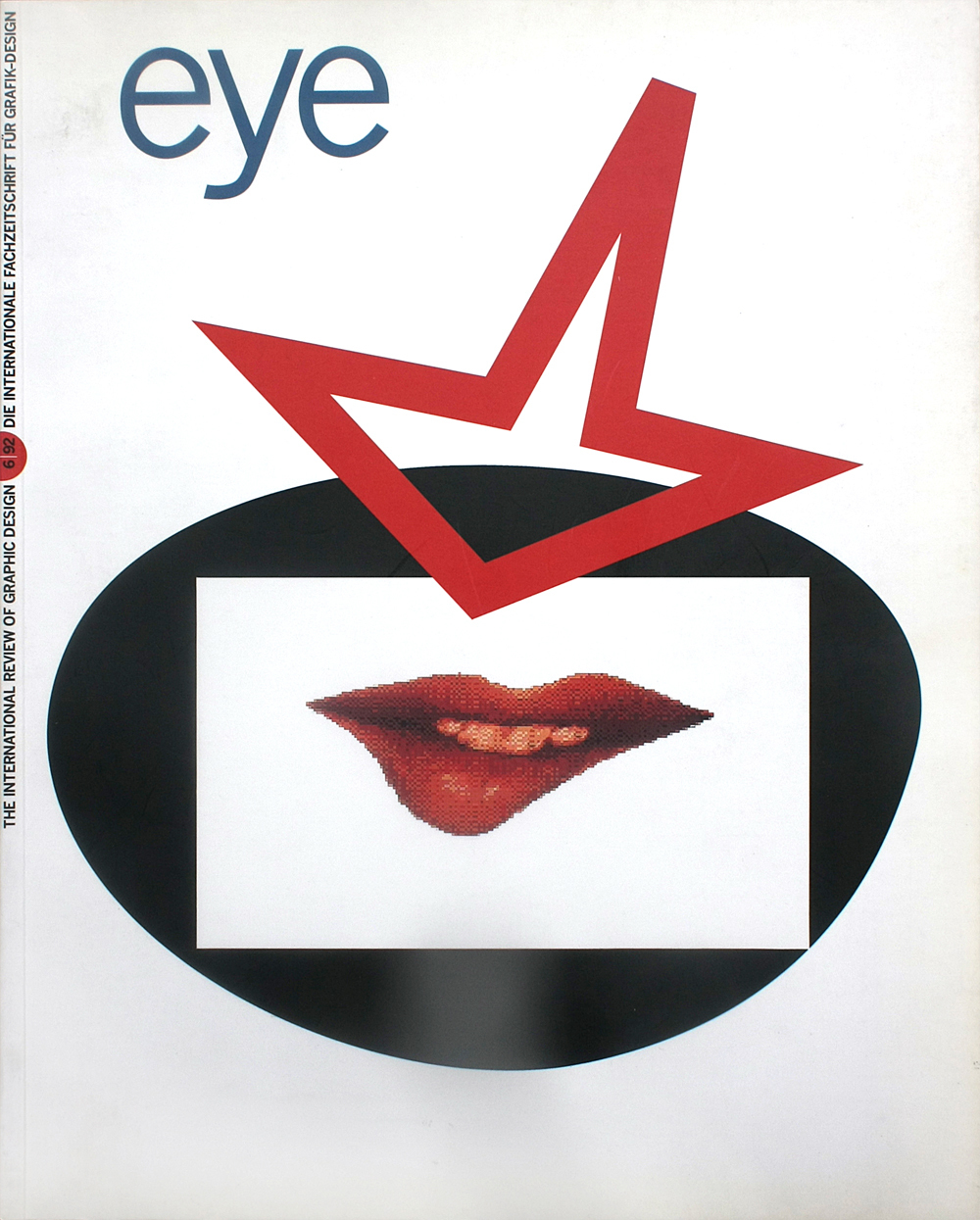

First published in Eye no. 6 vol. 2, 1992

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.