Friday, 2:00pm

24 October 2025

Design history in Ankara

Jessica Jenkins reports from the Design History Society’s annual conference, held at Ankara Bilim University, 4-6 September 2025

The papers presented at this year’s Design History Society annual conference in Ankara, Türkiye, reflected the growing international reach and diversification of the field. The overarching theme Design in the Creative Economy highlighted many examples of how transnational and corporate interests identify design as a means of economic regeneration and graphic design as a means of myth and identity-building. Graphic designers may be barely recognised for their role in these processes, but globally in colonial and post-colonial contexts their talents have been enthusiastically employed.

Xiaolian Qi and Xiaomo Wan revealed the successful advertising strategies of the British American Tobacco company in China in the face the 1925 anti imperialist movement. BAT successfully localised its cigarette packaging, both securing loyalty to the brand and launching the careers of some Chinese designers.

Hannah Pivo showed how the upward curve of a graph in early 1920s business-to-business advertising in the United States was initially a device to confer statistical objectivity on commercial claims, but eventually functioned as a formalist and potentially misleading graphic device.

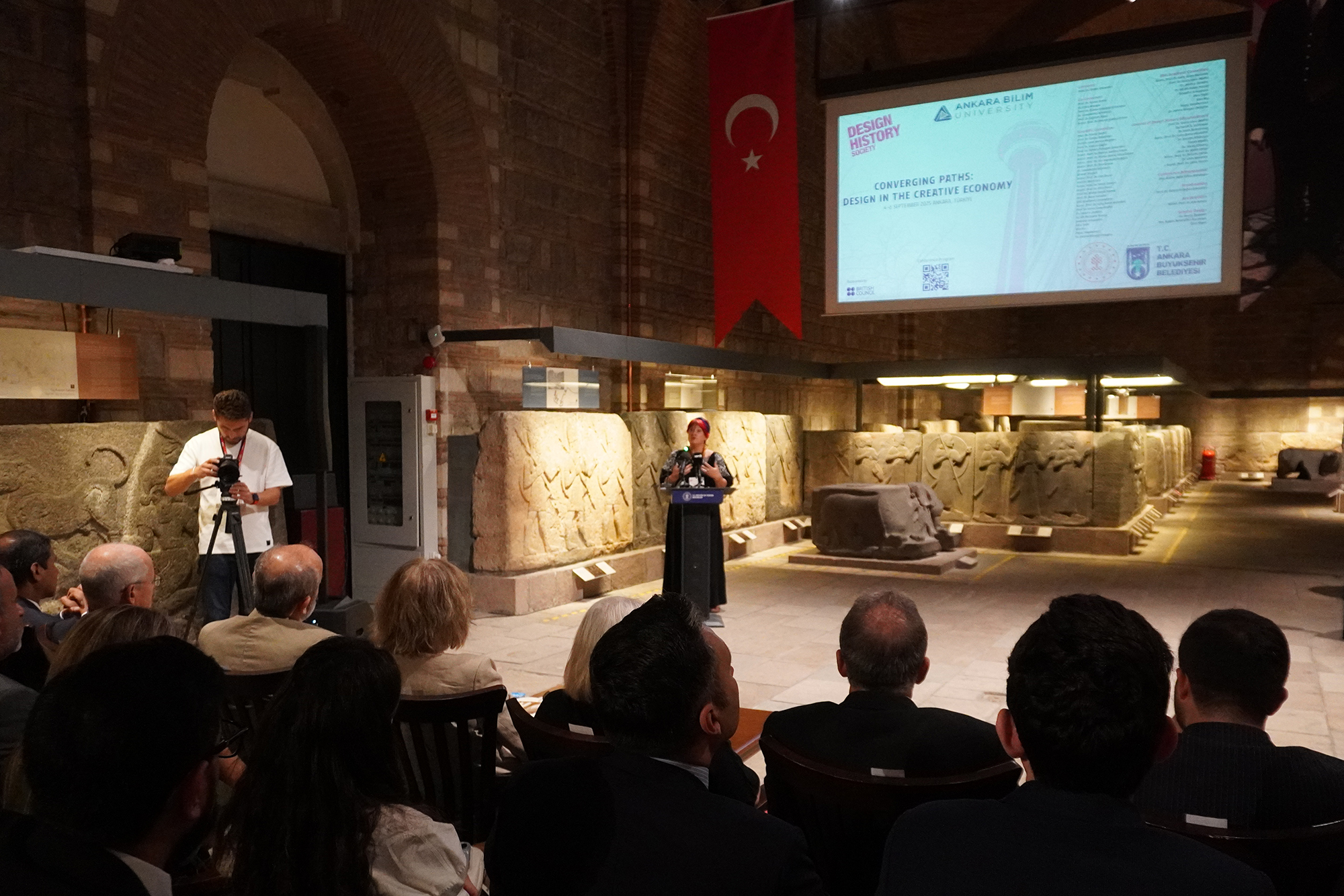

British Council poster (designed by Johnson Banks, 1998). Top. Opening event at the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara. Photograph: Ankara Bilim University.

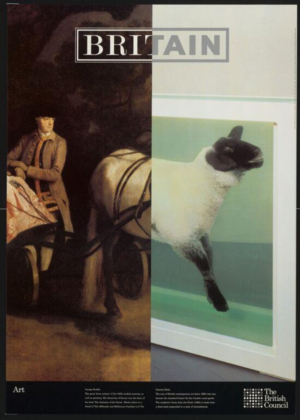

Cover for the magazine version of the 1997 New Labour manifesto, design by Giant. Below. Inside spread of the magazine.

In the late 1990s, the Tony Blair-led Labour Government in the UK was one of the first to employ design for the branding of a nation itself. Trond Klevgaard examined how this played out graphically in an era of ‘post-post modernism’, in which the irony and deconstructive urge of postmodernism was replaced by a binary projection in which Britain was to be seen as cutting edge while not relinquishing traditional heritage narratives. The demand for variety in accelerated capitalism saw ‘New Labour’ re-brand its Department of Culture, Media and Sport with a new logo available in ten colours to be used alternately – surely no coincidence that this came after the advertisements to ‘collect all six colours’ of the new iMac.

Design as a means for economic renewal and nation rebranding is now a global phenomenon, while not always including the voices or interests of creatives: Carolina Aranha and Isabella Perrotta claimed that design’s potential in Brazil is not sufficiently defined as it is put in service of a ‘creative economy’ while Enya Moore set out the social contradictions of ‘Cool Hibernia’, Ireland’s booming design economy.

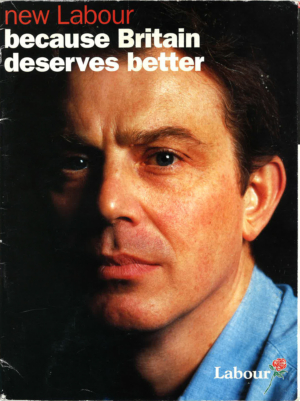

Posters show the progression from Applied Arts museum (1979) to Design Museum (2001).

Tupperware, 2005 (left). Coca Cola 2011. Designer: Piet Vandekerckhove. From the collection of Design Museum Gent.

Design was embraced in many countries as an economic driver in the era after Modernism: Lisa Sneijder showed how museums of applied arts transformed and commodified themselves as design museums, emphasising experience over education and adapting reassuring signifiers of Modernist design in their graphic communications.

Left. Found image, source unknown. Right. Meme made during ‘Meme Things First’ seminar, UIAV, Venice, 2024.

But designers are not always conduits for these kinds of political and economic purposes. Many papers demonstrated how designers resist, and can actively shape alternative methods, tools, spaces and forms of collaboration.

Rebecca Bertero and Serena de Mola showed how students deploy meme culture to articulate the contradictions of learning critical thinking while preparing for the unrelenting precarity and demand for conformity of the job market. This theme resonated in Christina Raddiedine’s paper, as she argued that today’s ‘hustle culture’, in which designers must perform their identities as a proof of their ‘passion’, is a logical extension of earlier design education values. Chris Lange pointed to the costs of design practice today, which depends on paying creative rent to big tech, and proposed an alternative ‘Anti Subscription Catalogue.’ Katie Krcmarik, presenting several innovations in desktop printing presses, showed how small-scale design solutions can also find their place in a global economy.

It is 30 years since Martha Scotford argued for ‘messier’ history of design, and since the late Bridget Wilkins and others demanded ‘No more heroes’, more focus on processes, mediation and consumption of design to destabilise the canon which emerged from this relatively young discipline. These names still appear on introductory slides as though this work has yet to begin. Yet the papers at Ankara suggest that such lines of enquiry are well established.

Etelia’s brochure promoting Stempel’s typefaces in Italy. Tipoteca Italiana Fondazione.

Mahwish Rasool and Ume Hasan demonstrated how they used the typography of Karachi’s urban fabric as a ‘database’ to read a history of overlapping cultural identities in that city. Ludovica Polo showed the role of distributors and printers in influencing typographic taste across Western Europe through fairs, samples and promotions from the 1950s to the 70s.

A panel led by Rebecca Houze and Jasner Galjer (Carolina Magana, Megan Brandow-Faller, Julia Secklehner, Marta Filipova) called for a feminist historiography that identifies ‘in-between’ spaces of female design activity, with examples of collaborative work in culture, health and education, and the cultural transfers arising from economic migration to the USA in the early twentieth century. Such transfers continue in today’s geopolitical relations, as evidenced in Lara Balaas’ reflections on Arab graphic and type designers working in Europe who gradually assert their agency and Arab identity.

How should new histories be researched and mediated? Bertero and de Mola suggested that crowd-sourced participatory archives might change our understanding of what counts as material for design history and Kristen Coogan’s Boston students created an alternative ‘Design History Reader’, generated through the diversity present in the classroom, which threw up interesting categories such as ‘spectacular gimmicks’ and ‘the dark fantasy’.

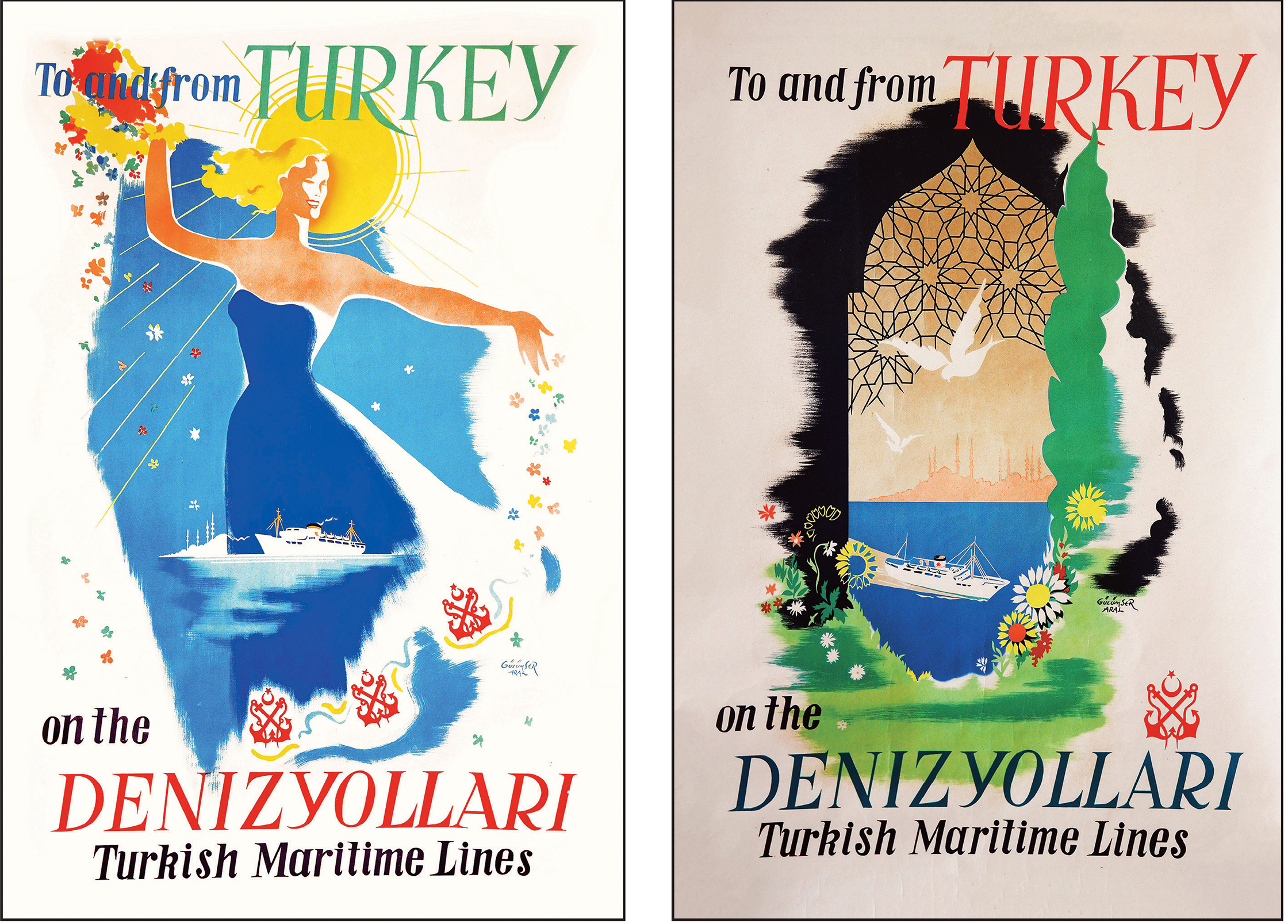

Two poster designs for Denizyolları, ca. 1950s. Credit: Gülümser Aral Üretmen. Courtesy of the Ömer Durmaz Archive and shown in ‘A Pioneering Turkish Female Graphic Designer’, by Ömer Durmaz and Murat Ertürk, in Women Graphic Designers: Rebalancing the Canon edited by Elizabeth Resnick, 2025.

Elizabeth Resnick presented her new book that uncovers the struggles and successes of 42 women designers across the globe in male-dominated design professions. She made the case that biographical research – which expands rather than entirely circumventing the canon – is still compelling. Women Graphic Designers: Rebalancing the Canon, edited by Resnick, is published this month (October 2025). The book includes several articles written by Resnick for Eye.

Clearly, the process of diversification is for each generation to re-define, but it is important to embrace the many ways of telling design history. Next year’s conference, ‘Design in an Age of Uncertainty’, will take place in Brno, Czech Republic, from 3-5 September 2026. New insights into graphic design history, still slightly underrepresented as a design field, are welcome.

Dr Jessica Jenkins, design historian, educator at Falmouth University and Trustee of the Design History Society