Winter 2002

Political clout: Australian posters

Screenprints gave both activists and artists a means of direct expression

Images of dissent have flourished in Australia since the first years of European occupation: scrawled graffiti by convicts in Sydney, satirical wood engravings and etchings in nineteenth-century magazines and trade union banners – all highly public expressions of solidarity. While the twentieth century was the age of the printed image, those with alternative ideologies have not usually had access to advanced forms of printing technology. Instead, they have had to use other means, and screenprinting was one of the most effective. The equipment was easily manufactured, and large numbers of colour posters could be printed relatively cheaply. Screenprinting was practised commercially in Australia from the 1930s, but it was not until the late 1960s that artists capitalised on its potential as a political tool. By the 1970s, screenprinting was being taught in printmaking departments in art schools around Australia.

Many groups involved in the campaigns against the war in Vietnam began to produce posters. Chips Mackinolty, who would become a key figure in the radical poster movement, recalls his introduction to screenprinting at a centre known as ‘Resistance’ in Goulburn Street, Sydney. ‘There was a room out back, perhaps 15 by 30 feet, where there was a screenprinting workshop… the meeting room was covered, late 1968, early 1969, with a multitude of posters that had been produced out of the Vietnam Action Committee and Screw (The Society for Cultivating Revolution Everywhere)!’

During the 1970s, political poster groups and alternative print workshops formed in many Australian cities. Screenprints were a way of making art and expression available to the whole community. ‘So long as art, in any of its forms, limits itself to the domain and interests of any one section of society, it will assist in the maintenance of social and economic divisions of that society,’ writes Toni Robertson. She worked with Earthworks (see overleaf), the most widely known and influential poster group, which operated from the ‘The Tin Sheds’, a cluster of Second World War prefabs at the University of Sydney.

Feminists were active in poster groups: Matilda Graphics, Women’s Domestic Needlework Group, Harridan Screenprinters and Lucifoil Posters in Sydney; Bloody Good Graphics and Jill Posters in Melbourne. The Anarchist Feminist Poster Collective was an Adelaide group. Among other Melbourne groups were Permanent Red, Breadline and Cockatoo; the Poster Workshop was based at Monash University, while the Wonderful Art Nuances Club worked from the Gippsland Institute of Technology.

By the end of the 1980s, teams such as Redback Graphix (see pages 44 and 45) were broadening their scope and diversifying their activities. The escalating costs and health risks of screenprinting and the arrival of desktop technology meant that it was no longer central. Many artists who were involved with the poster collectives moved into graphic design and few of the workshops survive. Green Ant Research and Arts and Publishing, in Darwin, is one of the exceptions. Its founder, Chips Mackinolty, continues to produce posters of power and conviction.

Earthworks

Colin Little, a former engineering student and university dropout, established the Earthworks Poster Company in 1971. Its poster style was initially derived from the late-1960s ‘decadent’ graphics of the British counterculture (see Eye no. 42 vol. 11) and the psychedelic posters that had flourished in San Francisco.

Little adopted this decorative style to highlight social issues. Alternative lifestyles, based on co-operation, self-sufficiency and responsibility for one’s actions, had been galvanised as a by-product of widespread opposition to Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War. Hopes were high for the ‘dawning of the Age of Aquarius’, enshrined by the Australian Union of Students at the Nimbin, Back to Earth, Festival of 1972, the year in which Gough Whitlam’s Labor Government was elected.

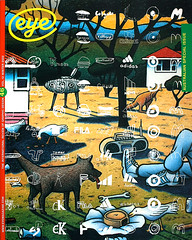

Earthworks’ posters reflected the broad social concerns of the time and were often signed with such slogans as ‘Another social reality by Earthworks Poster Collective’, or ‘Earthworks for the good of the community’. They advertised musicians such as Bo Diddley and Fairport Convention; the Australian drug film Dalmas; and Yellowhouse in Sydney, an environmental ‘happening’ and homage to Van Gogh associated with Oz art director Martin Sharp. Art Nouveau, gum leaves, rune alphabets, UFOs (flying saucers or ‘unlimited freak-outs’) and mind-bending tributes to the work of Escher were all part of Little’s visual vocabulary. The Earthworks symbol was composed of mystic symbols of the Egyptian pyramid and the evil eye.

In 1972, the company became a collective and expanded during the following years, many of the newcomers being art graduates. The women who worked at Earthworks during these years were particularly influential. Most had art training and a new professionalism became evident. Chips Mackinolty describes Marie McMahon as the first of the new wave of people, who brought in ‘a new aesthetic and new colours and ways of approaching stuffc … a really, really precise printer … one of the most exacting in terms of wanting it just right.’

After the momentous sacking of the Whitlam Government in 1975, Earthworks became even more stridently political, and emphasis shifted away from general lifestyle matters towards specific issues. Aboriginal land rights, gay and lesbian rights, the women’s movement (1975 was International Women’s Year), anti-nuclear concerns, the environment and unemployment became central themes. They had access to more sophisticated equipment and employed increasingly professional techniques. Later works used photo stencils printed in sharp flat colours to produce posters of iconic power. Pasted up at night around Sydney, these posters helped to politicise a generation.

When Earthworks disbanded in 1979 its members dispersed, many working in community groups and establishing new workshops across Australia. These include Jalak Graphics, Marine Stinger Graphics, Green Ant, Social Fabrics, Déjà Vu, Acme Ink, the Megalo Screenprinting Collective, Lucifoil Collective and Tin Sheds Posters.

Redback

In 1979, Michael Callaghan, who had worked at Earthworks, set up a screenprinting workshop and established Redback Graphix at the Film and Drama Centre, Griffith University, Queensland. In the following year, he moved the company to his home town, the industrial city of Wollongong, south of Sydney.

At the outset, Redback had a defined artist-client relationship. It was not a collective or open-access printing studio, but a graphic arts workshop where the work was organised on a professional basis, with wages paid and fees charged accordingly.

The posters produced at Redback in the early 1980s dealt with issues affecting the mainly immigrant population who worked at the BHP steelworks in Wollongong. Redback earned a reputation equal to its name by relating to strikes, local politics, unemployment and community issues – with posters often presented in two languages. A distinctive style emerged during this time: posters became larger with a central image flanked top and bottom by text. The colours they chose had a fluorescent intensity accentuated by the use of black.

‘When we got access to typesetting, things started to change,’ notes Callaghan. ‘The formula lasted like that for about two, maybe three years … We’ve always used fluoro colours a lot, it’s the basis of most of our stuff. Fluoros are used to bump other colours up to look brighter than they do if you use them straight out of the formula pigment.’ Fluorescents, he adds, were ‘cheaper than other inks’.

Redback’s move from Wollongong to Sydney, in 1986, signalled a major change. Grants for special projects were proving harder to secure and they decided to create a financially viable graphic art workshop catering for socially minded groups and individuals. Redback diversified its design work and became involved in the production of a range of products aimed at far larger, often national and international audiences. New clients’ requirements led to different media approaches: for Film Australia, Redback developed a range of promotional products as well as designs for offset lithography and screenprinting.

Many former Earthworks artists worked at Redback, as did people from other workshops, and the style of screenprints changed as new people joined, bringing with them special expertise. Photo stencils – sometimes from specially painted backdrops – were combined with mechanical tints and handcut stencils.

Despite this broadening of range, the needs of smaller audiences continued to be addressed. The posters on grog, AIDS and healthy tucker produced in consultation with Aboriginal communities are successful examples of Redback’s co-operative targeted approach.

Roger Butler, senior curator, Australian Prints and Drawings, National Gallery of Australia

First published in Eye no. 46 vol. 12 2002

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.