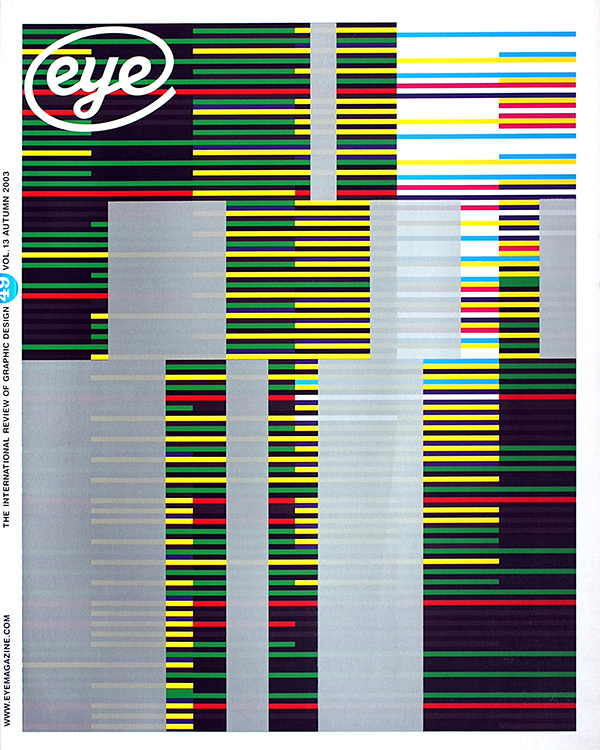

Autumn 2003

The end of Swiss graphics

Pathfinder: A Way Through

By Happypets Products. Laurence King / IdN £25.00Edited and conceived by the Lausanne-based experimental group Happypets, Pathfinder: A Way Through Swiss Graphix showcases the work of more than twenty young Swiss graphic designers, examining their ‘environment’, ‘codes’ and ‘habits’. In the style of a tour or itinerary, Pathfinder comes with a large fold-out map that attempts a graphic rendition of the work represented by each of the specific cantons and communes in which the designers reside.

With any new collection of work by young Swiss designers, it has often seemed obligatory to define their efforts against the architects of the neue Grafik style. Yet, as the social and cultural conditions that gave rise to that particular project are fading from view, seeking either commonalities or challenges to its purely constructive approach is fast becoming a critical cul-de-sac. It is to the book’s credit that it attempts to neatly circumvent this line of analysis by both drawing on and subverting alternative traditions of imagining Switzerland. In part, these are the icons of the picture postcard Swiss landscape – the images of vast mountain ranges, green pastures, and alpine villages that have been a significant feature of the popular imagination since Emil Cardinaux’s 1908 Matterhorn poster.

Over the past century, this image of Switzerland has continued to be cultivated by some of the most significant designers in its history. The difference now is that Pathfinder knowingly acknowledges this clichéd iconography as simply one brand among many others – comparable to the free-floating ambassadors of ‘Swissness’ that occupy every airport shop (chocolate, cheese, etc.). In the Happypets graphic introduction, this link is made literal when the Matterhorn itself is rendered as a half eaten Toblerone, and brand logos such as Apple and Lego are paraded as interchangeable with mountain views. Once this idea of ‘Switzerland’ is revealed as being just that – an idea – the need to create illusory imagery responsive to a priori assumptions about this country evaporate.

Thus, in designs by Raar, Fulguro and Electronic Curry Ltd, clunky graphics, gauche pencil sketches, and naïve illustrations are free to interact across the page with sleek computer graphics and photographs. This collection is a mixed bag of naked self-promotion, book covers, site specific installations, magazine designs, and flyers. The anthology is so dissimilar in fact, that the book’s overextended title is the only thing holding this mishmash of designs together.

In the book’s central essay, Tan Wälchli provides an accurate summation of this narrow space between image and place that Pathfinder seems to occupy. He states that if ‘the subject tries to become identical with the object, the result is that the object becomes shadowy and the mind ghostly. The only possibility, therefore, is to become conscious of the fact that the shadowy object was already partly produced in the mind.’ The key word here is ‘partly’. After looking through this anthology, I was still left with the question of what are the uniquely local determinants that have impacted on this work? If, as Happypets note in their brief conclusion, ‘Switzerland doesn’t exist’ but is rather ‘an invention of the Swiss graphic designers’, where do these inventions come from? Is it even possible to still speak of a distinct thing known as ‘Swiss graphics’?

In an anthology aiming to represent a broad sampling of contemporary Swiss design, the disparate works on show here would appear to answer ‘no’. Maybe the legacy of the neue Grafik has not been totally eclipsed after all. As is widely known, the consistency of form and technique that characterised that particular approach was regularly labelled the ‘Swiss style’ outside its homeland. While the achievements representative of that style no longer dominate graphic design in Switzerland, the desire to assemble contemporary work under that highly successful brand name clearly remains.

If Happypets truly wished to critique the outdated idea of an all-embracing concept known as ‘Switzerland’ in design, they could have done no better than to forego subtitling their own book ‘Swiss Graphix’.

Kerry William Purcell, design historian, London

First published in Eye no. 49 vol. 13, 2003

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.