Autumn 2000

Time, motion, symbol, line

Choreographers through the centuries have made brave, often beautiful attempts to visualise and record their work. Technology provides new means, but scoring a moving, dancing body in four dimensions remains elusive

Western classical music developed the way it did in part because it found a way to translate what was happening on to paper and literally ‘see’ it in the mind’s ear. Dance has never really found such a system, or at least not one as successful or durable. How do you ‘see’ four dimensions at once? How do you catch the shifting and subtle changes of dynamic in the body?

Writing dance is the exception rather than the rule, and the impossibility of pinning it down has become a quality of the artform, a defining freedom. Dance can go on re-inventing itself, always concerned with the authenticity of the moment, always free of its own history. Yet dance-makers have at times needed some way of recording their work, an overview, a way of reading and writing movement in time and space. The results are a private but often beautiful code.

Each act of choreography is an attempt to create a new language with the body, and each choreographer has a unique voice and an individual way of communicating that voice. Dance-makers will use whatever is at hand that enables the translation of sensation, ideas or feeling into movement, and that helps communicate and record the work. Notation divides into two kinds: the various attempts at a complete system to write down work that already exists; or the score as a notebook, a tool to find something new. Western theatre dance is a relatively young artform with its origins in the spectacles of the seventeenth-century French court. So we begin with the body as a site of wealth and status, an image still persisting in the classical ballet that grew out of it. However, the twentieth century saw dance place itself at the centre of rapid change that was Modernism, and out of this came an explosion of new forms. Whereas ballet took 300 years to develop, this new dance encouraged the individual and evolved rapidly. Dance-makers such as Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham began to invent their own techniques, usually modelled on how they moved and with far more complexity of twist and fall.

In the 1960s the dancer-choreographer hierarchy itself started to be questioned, and improvisation asserted itself as an important tool again. Today a dancer can draw from many different movement philosophies, and be expected to share the making of the work with the choreographer. All of this poses a problem to the complete notation systems, which are slow to use, but it has led to some wonderful uses of graphic scores and notes by contemporary dance-makers.

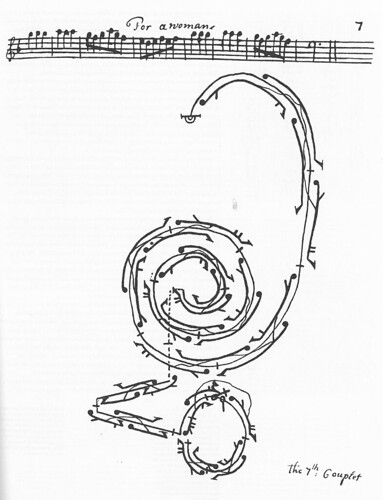

The first commonly used methods for scoring dance are the elaborate curling ‘track drawings’ of the eighteenth century. These documents shorthand the basics of each dance, dealing mainly with the feet and where to go in the space, and assuming that the style of the period is understood by the dancer. Like other dance graphics, they carry something of the quality and spirit of the thing itself, a kind of aristocratic grace.

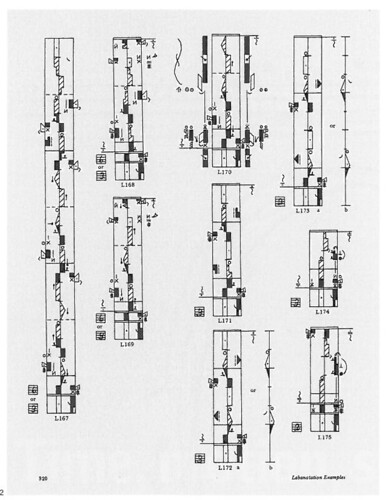

The ‘circuit-board’ look of Labanotation changes little from dance to dance, but hides a wealth of detail about the time, weight, space and flow of movement. This is a transcription of an eighteenth-century dance similar to the top image, though it couldn’t look more different. Labanotation was developed in the 1920s and 30s.

Top: An eighteenth-century dance seen from above with music notation running across the top. The author of this dance, Kellom Tomlinson, wasn’t blind to the decorative appeal of the drawings, since he also sold them as ‘paper furniture for a Room or Closet … if put in Frames with Glasses.’

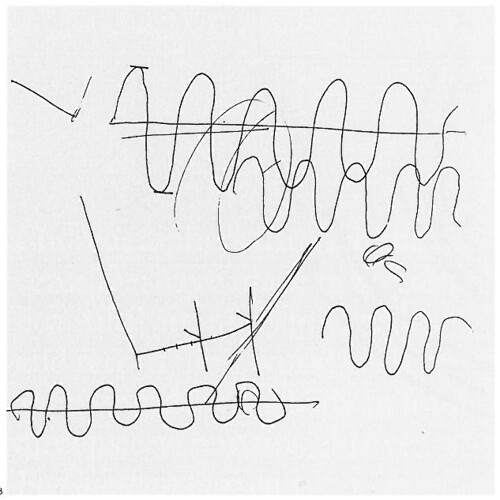

A page from the notebook of choreographer Rosemary Butcher, showing preparatory time and space drawings for her 1999 piece Scan. Rough notes like these help visualise texture and keep track of the process.

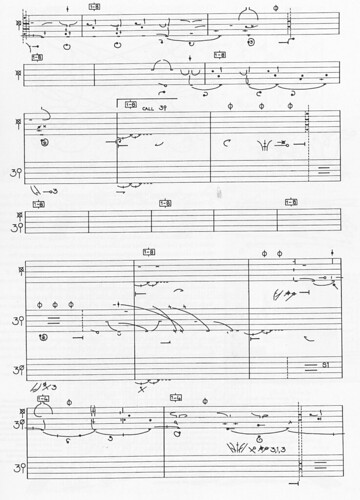

It is difficult to write the detail of the body in dance once you get into the torso rapidly spiralling, with arms and legs moving out of sync. Complete notations work best for systems that are already codified, such as court dance or classical ballet, where you can draw the sweep of an arm, and the detail is understood. Benesh Notation is a complete system that has worked well for ballet. Developed by Rudolph and Joan Benesh in the 1950s, it employs a five-line stave, with the bottom line for the feet and the top for the head. Movement is drawn as curves across the lines: it deals best with the geometry of ballet. Classical ballet companies across the world employ an army of people to write and re-interpret this system but despite being taught at ballet schools it has never really become the universal tool envisaged by its designers.

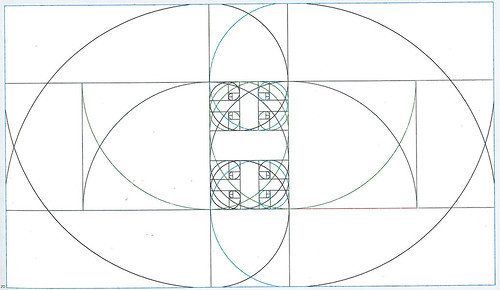

Another successful movement notation of the twentieth century came out of the work of a Hungarian movement researcher called Rudolf Laban. He saw the body as occupying what he called a ‘kinosphere’, determined by how far we can reach our limbs out in a three-dimensional circle from our centre, like Leonardo da Vinci’s spreadeagled man. He analysed movement as a combination of four things: time, weight, space and flow. His theories of dance were part of the inter-war German interest in the body and nature. The notation system based on his ideas was developed in the 1920s and 1930s by his pupil Albrecht Knust. It looks like what it is: a painstaking scientific breakdown of the movement.

After being banned (at the last minute) by Goebbels from showing his choreography at the 1936 Olympic Games, Laban fled to England. There, he put his ideas to good use for the war effort, by giving classes to factory workers in ‘Laban-Lawrence Industrial Rhythm’, an early time-and-motion study that sought to improve efficiency at work. His analysis of the body in motion remains important, though, and is one of the tools used by American choreographer William Forsythe (with his company Ballett Frankfurt) in his deconstruction of ballet.

A handwritten page of Benesh notation showing part of a dance for seven men from Kenneth Macmillan’s 1974 ballet Manon. The body is seen from behind with the head on the top line and the feet on the bottom. Sweeping curves graphically illustrate the flow of the movement.

The process of dance-making today is organic and intimate, one on one: it does not lend itself easily to being overformalised. There is a blurred line between maker and performer, each bouncing things off the other in an endless feedback loop. The choreographer throws ideas to the dancers, trying to find the thing that best enables each unique physicality, which is then shaped and edited immediately. The job of the performers is to stay two steps ahead, responding fast to each image, task or word and trying to embody them as their own, often making the material themselves. The choreographer is also searching for the bigger picture, and dance is only one part of this. As the process grows and work in the theatre begins, then sound, design, light, and often text and film add more layers and textures.

In the middle of all this complexity it can be difficult to step back and reflect. Many dance-makers today use some kind of notebook to give them back some private space in the chaos of the studio. Often these notes are a private reference point for the choreographer, but occasionally they become a hieroglyphic that the dancer must translate directly. If a visual image is used like this to find movement, it is usually only a clue, a way to push the imagination of the performer out of habitual ways in the manner of some graphic notation for music (see Eye no. 26 vol. 7). Any piece of choreography, any score, can work only if it enables the dancers to rediscover their own internal dance and let them take flight. Without that there is no life.

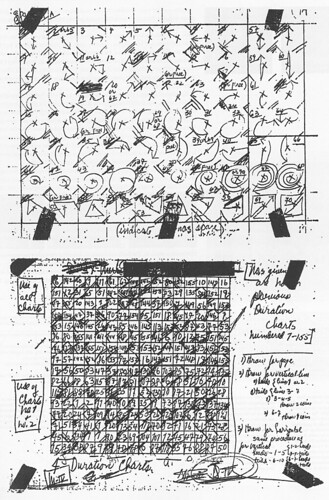

Merce Cunningham, one of the giants of the American modern dance movement, has always used scores to make his dances. Without these charts and drawings the complexity of spatial and rhythmic detail in his pieces would be impossible for him to orchestrate. Cunningham’s scores inform the whole idea and landscape of each piece. It is probably his work with the composer John Cage that influenced this unique and musical approach to dance-making, starting with the rhythmic structures they shared in the 1940s. These structures divided time mathematically into pre-decided ‘parcels’, which each could fill in his own way. This experience of working in parallel but without being tied to each other was followed by their discovery in the 1950s of chance methods of composition. Cunningham would have a chart for each aspect of the dance, with dice to be thrown for every possible choice of time, space and movement. The process was laborious, but the pieces that emerged from it led to a new way of seeing performance itself. Multiple events could unfold on stage at the same time and the overlap of different elements was constantly shifting and open to change.

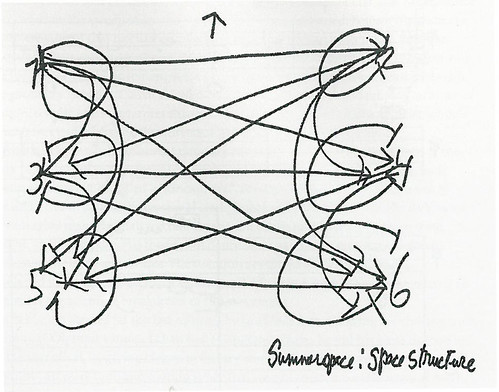

A space plan for Merce Cunningham’s Summerspace, 1958. The drawing contains the idea for the whole piece: six dancers, six entrances, each dancer will make all 21 possible crossings of the space using 21 different kinds of movement phrasing. The order

of events was derived from chance operations.

What Cunningham calls ‘space trajectories’ for Summerspace.

This drawing shows two different ways of getting from one entrance to another, not necessarily by the shortest possible route.

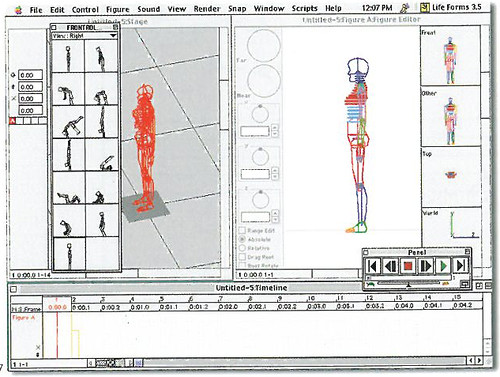

A window from the animation software program Lifeforms developed in collaboration with Cunningham in the early 1990s. The figure is modelled into shapes stored in the shape library on the left. By placing two shapes on to the timeline at the bottom, the programme will animate the figure from one to the next. Figures can be dropped on to a stage and seen in three dimensions from any angle. Cunningham’s recent piece Biped, made using this software, can be seen at The Barbican, London, this October [2000], along with Summerspace.

In the past ten years, finding it harder physically to work out the phrases from his charts, Cunningham has turned to computer technology. The Lifeforms software was developed with his help from an animation program. It gives you a digital body and a library of shapes, a timeline for each body in the piece, and a stage that can be looked at from any angle. The current obsession with all things digital means that these pieces are marketed as ‘cyberdance’, but they are a logical continuation of a way of working Cunningham has followed for years. That this is another tool, another way of enabling the event itself, is what makes it radical. In his short autobiographical text, Four Events That Have Led to Large Discoveries (1994), Cunningham lists rhythmic structure, the discovery and application of chance procedures, film camera techniques and the use

of software as the moments of important change in his work.

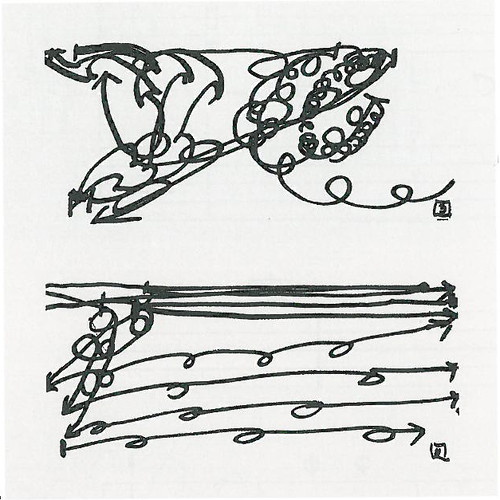

Direction and duration charts for a complex Merce Cunningham piece Suite by Chance, choreographed in 1953. This was the first dance piece he made where everything was decided by chance, and coincided with the early use of chance methods by composer John Cage (also Cunningham’s companion and collaborator). A coin was thrown to determine what move, where, in which direction, for how long and with whom.

In the past ten years William Forsythe and Ballett Frankfurt have changed the image of ballet. Forsythe’s work has challenged the hierarchies of the form and deconstructed the classical body, making fierce and hyper-articulate dances. He has often used arbitrary timelines to decide when things will happen, written out as a score and then cued from digital clocks on stage. The timeline is often a way to pervert what he calls ‘anatomical’ time, the time of the body falling. It forces the dancer, for instance, either to complete a lot of movement in a short time, or to fill up a long interval with very little movement. Alongside these timelines are often other graphics, cut-ups and space plans, things that the dancer is forced at some level to translate, to understand.

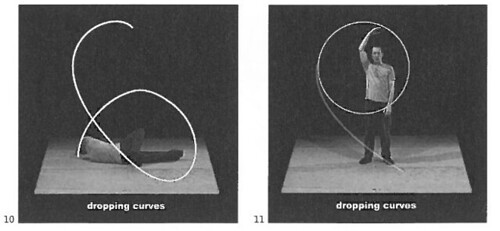

Two windows from Improvisation Technologies, a CD-ROM by American choreographer William Forsythe. The user navigates their way around a series of different methods of generating movement. Technology has allowed the makers to be drawn in lines of motion, articulating the hidden architecture of the dance. These windows show two parts of a section called ‘dropping curves’, which show the simultaneous circling and falling of the body in space.

Hypothetical Stream, a piece commissioned in 1997 by the French choreographer Daniel Larrieu, was faxed through to the studio as a series of scribbled marks over photocopies of preparatory drawings for Tiepolo paintings. The piece has been remade by four different groups of dancers, each group engineering a radically new dance, but each dance sharing some kind of spirit with its predecessors. Forsythe has also made a CD-ROM called Improvisation Technologies, where the line of the movement is superimposed on to the screen in white lines and the hidden architecture of the dance is made visible. More a facilitator for ideas than a score, the program, for instance, was sent to the Royal Ballet to use in preparation for Forsythe’s 1994 piece Firstext.

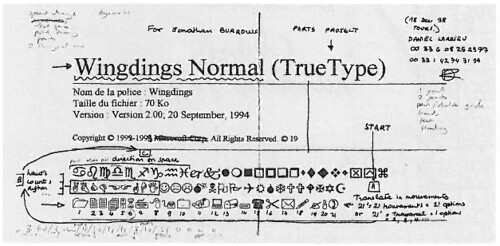

This is a score sent by Daniel Larrieu to Jonathan Burrows (the author of this article) who used it to make two dances, Rewriting and Singing, in 1999. The basic computer font Wingdings is used as a map, with instructions and choices as to how to proceed from A to B.

Scribbled notes will always be a part of the dance-maker’s tools, but the biggest revolution has just begun, with the advent of cheap digital recording and editing on video. Once the images are transferred to computer, the choreographer can cut and paste instantly, sculpting the shape of the event in time and sampling from any number of process tapes. Improvisations can be relearnt and a record can be kept not only of finished work but of the piece as it changes, grows or decays in performance. This is a tool for the dancer also, since one of the best ways to learn movement is to see it. When we see a movement, the neurones in that part of the body fire even if we do not actually move, and the brain immediately scans for similar patterns that have already been encoded. Video allows the dancer to look again and again as the information sinks in. The body can move on, knowing the earlier movements are stored safely on tape, and free the physical imagination to find new things.

The ideas that underpin choreography can be a rich source, complex and diverse, but watching dance is no mystery: what you see or feel is what is happening. The joy is that we are all silently skilled in reading body language.

Jonathan Burrows, choreographer, dancer, London

Five stills from the completed film of Hands.

A floor plan from In Real Time made by Belgian choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker earlier this year. These shapes were taped out on the studio floor and used to create complex space patterns.

First published in Eye no. 37 vol. 10, 2000

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.