Winter 2025

Ultra process

various designers

Hey Studio

Verónica Fuerte

Phillip Toledano

Rankin

Daniel Brown

Marcus Wendt

Jann Choy

Mucho

Studio Blup

Dines

Michael Johnson

Pum Lefebure

Design Army

Span

Field

Steven Ryan

Substance

Sebastian Koseda

Joseph Bisat Marshall

Christoph Niemann

Fromm

Marc Català

Ben Ditto

Tool, agent or end of days? John L. Walters asks designers and image-makers how and why they use visual AI and what this might mean for creativity

Right at the end of a conversation about text-to-image programs with photographer Rankin, he asked what I thought. This was one of dozens of interviews I conducted for this feature, and there was no satisfactory conclusion in sight. Several exceptionally gifted and clever people have helped me put this together, but there will be no neat summary about visual AI and how it might change graphic culture. Is what we see at the moment merely the equivalent of 1990s web design, early cinema or Fox Talbot? There is a long history of over-optimistic predictions, from decision-making machines to self-driving cars.

Yuval Noah Harari, philosopher, historian and author of Nexus says that AI is the first technology in history that is not a ‘tool’ but an ‘agent’: it can invent new things. The atom bomb could not invent the hydrogen bomb, for example. Andrew Smith, author of ‘coding odyssey’ Devil in the Stack, thinks that computers are nowhere near having the learning intelligence of bees or cuttlefish. His fear is that as computers fail to become more like us we might meet them in the middle – humans will become dumber to make use of AI applications.

For the purposes of this article I am concentrating on visual AI. Designers are approaching text-to-image software with a heady mix of excitement, curiosity, disgust, unease, pragmatism, disquiet and awe – and that is before we even start discussing the negative side, such as the sustainability issues addressed in J. P. Hartnett’s ‘Baked in’ (pp.70-71).

In Marian Bantjes’ ‘Artificial idiot’ (Eye 105), she and Design Army’s Pum Lefebure likened Midjourney’s progress to that of a child. To extend the metaphor, is AI in danger of evolving into an unsocialised ‘kidult’, consuming vast amounts of ultra-processed food, unable to engage with all but the most dedicated carer and making what Max Read, in a widely shared New York magazine article (‘Drowning in Slop’, Life in Pixels, 25 September 2024), termed ‘slop’?

Top. Image from @wonderlandbyhey by Verònica Fuerte. Right. Historical Surrealism. This AI-generated image is from We Are At War, by artist Phillip Toledano. ‘The fact that I was fabricating a possible fabrication was strangely interesting,’ says Toledano.

To return to Rankin’s question, a better reply would have been ‘déjà vu’. My instincts have always been to embrace new technology, first as a science student and sci-fi fan and then with the synthesizers, drum machines, ‘microcomposers’ and digital samplers of my music career. The idea that machines might replace musicians resonated widely and alarmed unions and cultural commentators. Technology companies promoted music computers as a way to save studio time and musicians’ fees with crass adverts they later played down. Cutting-edge tropes of 1980s tech quickly evolved into clichés you still hear on the radio today.

After moving into journalism, I found myself showing experienced writers, editors and designers how to use the new page make-up systems that transformed the way we made, corrected, designed and printed magazines and newspapers in the 1990s. Old jobs disappeared and roles changed. Flash ahead a few more years and I witnessed meetings discussing the sluggish websites that would give companies ‘more bang for their buck’, even though many people around the table suspected that this new medium, with its poor typography and low-res images, would eventually strip away jobs and re-route ad revenues. Nobody knew quite how and when and where, which is why we had the painful dotcom boom and bust. More recently we have seen the crypto and NFT bubbles, energy-guzzling entities that make little sense unless you are sited near the top of the pyramid.

Verònica Fuerte of Hey studio has been experimenting with AI program Midjourney for some time, posting the results on an Instagram account called @wonderlandbyhey. Images on this quiet feed have an intense colour palette and playful spirit reminiscent of Fuerte’s client work.

Philosophical conversations with lawyers

Rankin is both cautious and bullish. He has produced a series of ‘Cottingley Fairies’ pictures with model Heidi Klum, based on the notorious fairy photographs made by Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths in 1917. Interviewed in the 1960s, Wright said she had photographed her thoughts … which sounds like an AI prompt.

In his ‘F(AI)KE’ series, Rankin shows Elvis Presley, Muhammad Ali, Bob Marley and other famous faces, captured in his distinctive black and white portraiture style.

‘I’ve used Midjourney to open up a kind of visual conceit, and then retouched them,’ he says. ‘It’s effective, but not that cost-effective! You’ve got to spend quite a lot of money on retouching. Midjourney is so easy to use. I’ve got good at prompting from my own work – I can replicate my own photos. Legally, it’s a strange area, so I’m unsure what to do with them. I’ve been speaking to lawyers. I’ve never had such a philosophical conversation with a lawyer!

‘There are some people you cannot prompt. I can only imagine that the estates are so litigious, it’s baked into the program. Muhammad Ali is one of my biggest heroes. The only problem with the imagery of him is that 99 per cent of it has sweat marks. You have to take those away.’

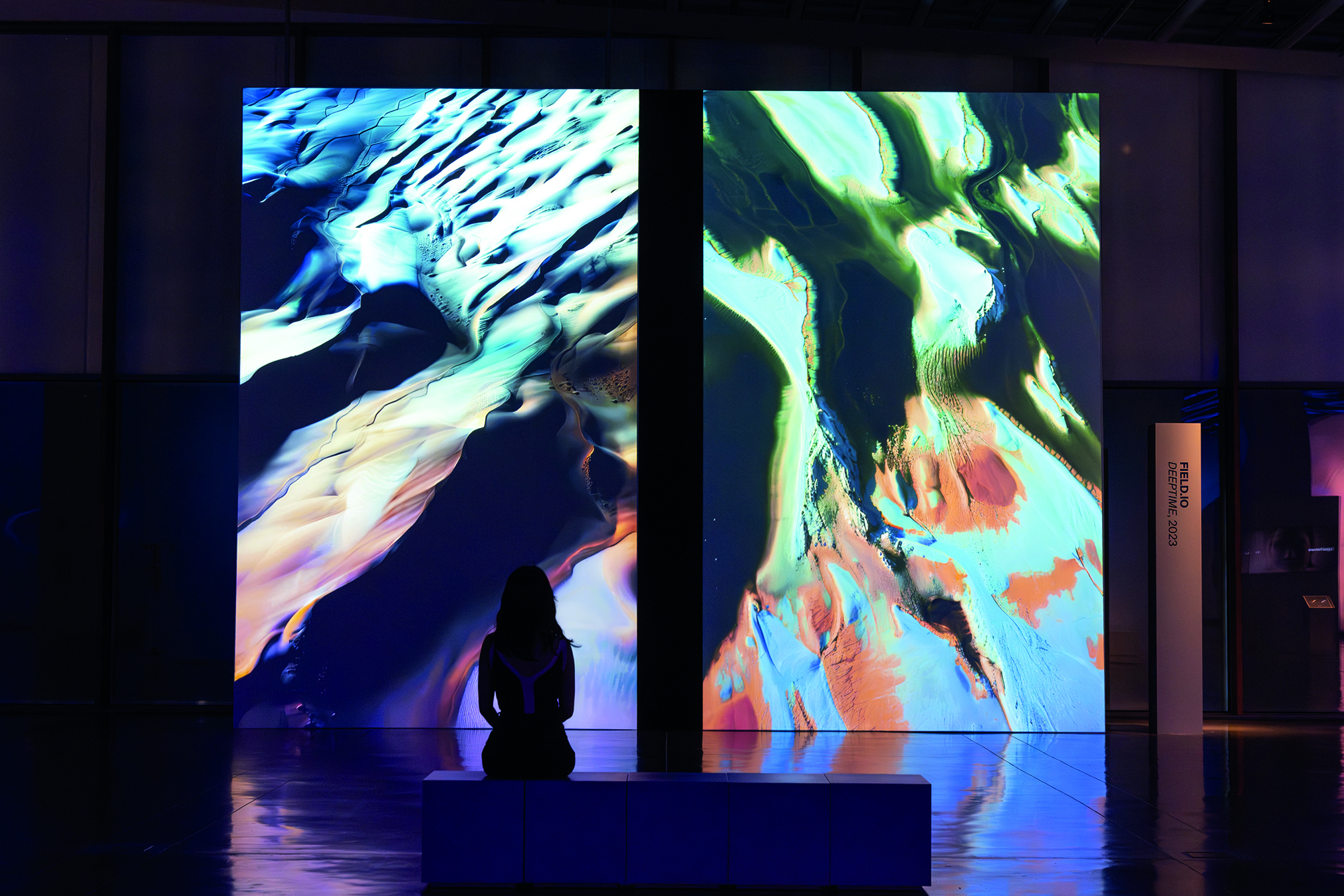

Photograph of Field’s 2023 installation DeepTime at Disseny Hub, Barcelona for ‘Digital Impact’ (28 April – 27 August 2023). The moving images are based on landscape imagery, using the programs Unity and Stable Diffusion.

Graphic designers are grasping the nettle of this shape-shifting tech, which many writers now place within scare quotes as ‘AI’. As artist Trevor Paglen told Aperture, ‘“Artificial intelligence” also doesn’t really mean anything … It’s a term that lends itself to mystification.’

Universal Everything creative director Joel Gethin Lewis agrees: ‘AI is a misnomer. I call it machine learning.’ Gethin Lewis, also a course leader at UAL’s Creative Computing Institute (CCI) in Camberwell, talks enthusiastically about the open-source ‘ecosystem’ that has sprung up around ComfyUI (comfy.org) as a way to have more control over such applications.

Discussing the look of visual text-to-image apps, he says: ‘One of the problems with a lot of the stuff that’s coming out is that it’s like a sugar high. You go, ooh, it’s a new visual aesthetic. And then … no, it’s not really, it’s nothing if you can’t control it and have some understanding of what it is.’ He is interested in using machine learning for display systems that will permit perfect augmented reality. ‘That opens up huge new fields in terms of graphic design, visual communication and interaction.’ Gethin Lewis introduces me to his former CCI student Jann Choy, who joined Field (see Eye 80) straight from college. In 2023 Field exhibited the huge installation DeepTime in the Disseny Hub, Barcelona for Digital Impact, an artwork intended to show the slow, constant transformation of the Earth’s surface.

‘It’s ironic, isn’t it? Using AI to reflect on climate change!’ says Choy. ‘You can just add whatever detail you want based on whatever models you train. We wanted to have different geographic locations and some styles that inform the human impact on climate as well. All the datasets were datasets that we created. It was time-consuming … long processing hours. This was before Runway got really good.’

What does it feel like to work with visual AI programs like Stable Diffusion and Midjourney?

‘If you treat it as an equal, you can have a relationship with AI. Navigating it is almost like the horse dressage at the Olympics. It doesn’t always listen to you. Sometimes you just give into it and new things come out. Like with every tool, the best work is always where it has the most originality and most skill involved.’ Does Choy regard the different programs as having different personalities?

‘Yes, a hundred per cent. With Midjourney, the aesthetic is very clean. They give you a beautiful product, but then they have some weird fantasy elements. Whereas Stable Diffusion is Open Source, which is great, but that also means it could be anything. But you can have a lot more control over it. You can train your own models. And there is a whole community of people sharing stuff.’

Daniel Brown, whose digital work has anticipated many tropes of AI imagery for decades, explains that he is, ‘actually a bit of a Luddite, and rarely the first to adopt a new technology.’ In recent months his social media accounts have become the display board for an extraordinary parade of impossible architecture and tangled steel constructions within a fantasy urban dystopia, influenced by the earlier, non-AI images he devised for William Gibson’s ‘Sprawl’ series of sci-fi novels. ‘I am something of a convert to AI, in the right context,’ says Brown.

After all, the ease and speed of making images through text prompts is no trivial matter for a designer who is obliged to use a wheelchair. ‘The disability enablement “angle” is often overlooked in AI cynicism,’ he says.

‘Sometimes reality is not enough,’ says Etro’s creative director Marco De Vincenzo in a recent Financial Times report about AI in the fashion industry. ‘It’s modifying reality, but that’s what every creative [person] tries to do. It’s our job to try to escape and experiment.’

Generative city architecture by pioneering digital artist / designer Daniel Brown, head of interaction at SHOWstudio, who has been posting such pictures regularly on his Instagram feed @danielbrownimages. Brown selected architectural textures as Midjourney input images and entered a basic text prompt.

‘Politely and professionally terrified’

Design Army’s Pum Lefebure, whose Georgetown Optician campaign was shown in Eye 105, sees AI as yet another element in the design studio’s toolkit. ‘I’ve been in business for twenty years, so I’m always trying to be ahead of the curve and see where the market is going. Traditional design is not going to be sufficient. You need to get into photography and art direction. I was one of the first people to use Instagram, without even knowing what it was. AI is the same.’

‘I’d describe AI’s role in the studio as “assistive”,’ says John Pobojewski, a partner at Span in Chicago, ‘helping us make a project happen, but not defining it creatively.’ The studio has used AI to storyboard films, sketching 3D visualisations for a desert biome outside Riyadh.

‘We’ve been using it visually as a mock-up tool,’ says Michael Johnson (Johnson Banks). ‘For example, we’ve been working on a “timeline” to show how further education works for people at different ages of their life – an idea that was hard to visualise before without AI.’

Span’s Pobojewski was on the panel for a Chicago Graphic Design Club event about AI that included Steven Ryan of Substance Collective. At the Chicago event, reports Pobojewski, most of the audience comprised junior designers starting their careers. ‘I’d describe the tenor as “politely and professionally terrified”,’ he says. ‘Many folks were visibly nervous about what AI meant for their professional future. There were heated discussions from those of us on stage.’

Substance’s Ryan is enthusiastic about the new programs, using Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, RunwayML, ElevenLabs, Firefly and Soul Machines. He has created a set of artificially ageing faces for Morningstar’s ‘Evolving Investor’ campaign and a series of posters called ‘Br(ai)ve New World’, shown at the Design Museum of Chicago. (See pp.67-69.)

Lefebure, asked whether there were projects for which she would never use AI, replied: ‘I try it on everything. Look back at the 1990s – I don’t want to be the designer that’s still working with typesetters. You can be the best typesetter in the world, but it’s no longer relevant. I have to keep up – it’s not going to go away.’

She points out that graphic design has long involved things that studio personnel were not necessarily trained to do: AI continues this aspect of practice. ‘Five years ago you would need an animator, you need 3D model rendering, a lot of people who have some skill sets in craft,’ says Lefebure. ‘We still have those. But as a creative director, you may have a vision in your head and it’s coming at 11, 12, 2am in the morning and it’s like, okay, this is 3D typography of a letter “P” that makes up Stonehenge in solid gold floating in the middle of lake and a swan comes by. I have those ideas all the time. It’s going to take forever to photograph that. But it’s like “boom”. AI sometimes takes me to a place I didn’t even think of. You either pull back or just let loose and go with it. It’s like I’m the “mom” of AI. I trained this thing, but it’s getting smarter.’

Design Army’s Georgetown Optician work caught the attention of the Hong Kong Ballet, which needed a campaign for its 45th anniversary. For Lefebure, this was a chance to use AI for the concept but then shoot it for real.

‘There’s an emotional connection and empathy. I had an AI campaign but then I go back and shoot with people. The weather was bad, it was a long night, I was so tired because it’s like 150 people on set, but it was worth every minute. I needed this in my professional life, to work with people. I wanted to see the dancer jump in the air … it’s human. I remember coming back feeling really tired, but very inspired and fulfilled. With Georgetown Optician, we didn’t go to the desert, we didn’t build a set to look like Mars. We had a hundred characters but there’s no one – just me in my room right here. We didn’t have that connection in terms of the creative process. I have much more of a story to tell to my kids about Hong Kong Ballet!’

In San Francisco, Volume’s Eric Heiman has been using AI tools for one high-profile project (as yet undisclosed) but does not see them being folded into regular workflow yet. ‘We are not so much image-makers as complex systems creators: brand, signage and wayfinding experience, etc., and AI is not so helpful for that part of our work. When visual AI starts understanding the systems side of things, I’ll be excited – to eliminate some of the busy work and focus more on the ‘why’, the ‘for whom’, etc. – and scared to see if I still have a business.’

What about the ethical side? ‘Why are we in a rush to automate one of the best things about being human – creativity and art-making?’ asks Heiman rhetorically. He recommends Brian Merchant’s critical take on the subject in Blood in the Machine. Discussing similarities to when the Mac and PostScript arrived in the 1980s and 90s, Heiman says, ‘It seems more significant than that. It’s one thing to completely upend

the way we produce our work; it’s another to eliminate the producer altogether.’

Versions of these conversations are likely being conducted in design studios around the world. While some designers understandably, do not wish to get left behind, others grapple with the creative, moral and environmental costs and threats of using artificial intelligence.

Also in San Francisco, Mucho’s Rob Duncan considers its significance for idea-based design: ‘AI can create and copy styles easily but struggles with “Big Ideas”. Ideas require taking two concepts and giving them a clever twist to create something new and unexpected. Perhaps the future is safer for more conceptually based designers. Perhaps handcrafted solutions as opposed to such polished, generated solutions will have a resurgence? If not, everything is going to start looking and feeling the same.’

Image from The Cottingley Fairies Reimagined, for which photographer Rankin worked with model Heidi Klum and FTP Digital to make images that mixed AI with genuine photographs.

‘What a time to be alive!’

So if AI is a tool, created by humans, that extends the possibilities of what humans do, it is something that designers will have to grasp with both hands, and both sides of the brain.

‘What a time to be alive,’ says Sebastian Koseda, a designer and artist who for several years has been working for clients with machine learning at their core. These include Google Deepmind; the Creative Computing Institute; and SingulartyNet, a Humanoid animatronics company. In 2022 he designed an exhibition that explored the ways AI might change our lives. Though essentially positive, quoting Wim Crouwel’s dictum that ‘You are always a child of your time,’ Koseda takes a nuanced view. ‘As mostly digital natives, we have seen so much technological change in our lives it is hard to fear being made redundant. We are used to being responsive and adapting alongside technology. I grew up with a Nokia 3210 in my pocket – now I have this super computer data-harvesting surveillance device instead.’

Text-to-image programs have been welcomed in creative sectors that feed on images, such as design for theatre, television and film.

‘We’re ripping stuff off all the time,’ says production designer Joseph Bisat Marshall. ‘In film there is an acceptance of the derivative nature of what we do. We’re telling stories in believable spaces, even if those spaces aren’t real, and that requires grabbing references from (and copying) what audiences have already seen. We’re often trying to create what an audience thinks is right.’

Marshall makes a distinction between two uses. Firstly, the tools that save time while extending or redrawing a theatre set backdrop. ‘A task that could have taken a day or more to complete can now happen in five minutes.’ Secondly, there is AI’s ability to generate images. ‘It’s like having a concept artist sitting next to me that’s willing to mock-up all the ideas, rather than just the ones the direction and budget will allow. It’s useful when you don’t know exactly what you want, and incredibly frustrating when you do! I know big film directors that will now sit and generate images during meetings – to better explain what they’re after.’

Illustrators and cartoonists tend to take a different view. On an Instagram post of his twelve-panel strip for the Guardian (6 September 2024) Stephen Collins declares: ‘I fucking hate AI art and everyone that uses it.’ Collins’ strip shows Michelangelo completing the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in five minutes, to the amazement of a commissioning cleric, who peers closely and asks: ‘What’s going on with God’s hand?’

Reportage illustrator Lucinda Rogers (Eye 103), speaking at a recent London event, said: ‘We can all use our brains … but AI can only come up with something based on what has already happened.’ After all, text-to-image software depends upon the image-to-text stage – pictures that have already been tagged as part of the training process.

In an article about a recent cover for The New Yorker, Christoph Niemann cites ‘a wonderful new tool that lets you “poison” your art.’ He is talking about Nightshade, part of The Glaze Project, whose stated goal is ‘to protect human creatives against invasive uses of generative artificial intelligence or GenAI.’ The tools are free. According to its website, ‘artists across the globe have downloaded Glaze more than 5 million times since March 2023, and Nightshade more than 2 million times since January 2024.’

Apps such as Glaze, Nightshade and WebGlaze ‘disrupt unauthorised AI training’ on creative people’s work, or in Niemann’s words, ‘sow some chaos’ by inserting inaccurate tags into image files. This means that a cat, for example, could be tagged as a tree, a fish as a bicycle, a pipe as a painting: Surrealism and détournement as creative resistance.

Notwithstanding such deliberate disinformation, cultural commentator Ted Gioia, in an echo of the ‘slop’ problem, references experts who believe ‘AI will hit a brick wall,’ by 2026, having used up all human-made training input.

Asked about AI’s impact on the practice of illustration, agent and illustrator Darrel Rees, founder of the Heart Agency, says: “Any illustrator with a reasonable degree of success is going to find their work being copied. Rarely is it a clear case of copyright infringement, more a mundane matter of plagiarism as others try to make “looky-likey” work. With so many people sourcing so much of their information from the internet, it’s no longer surprising. AI is just an enhanced form of that plagiarism.

‘The question is, who will “consume” this enhanced plagiarism? Given that most clients value originality and authenticity, I believe they will steer clear of AI-originated work. We already have clients who ask for a guarantee that no AI is involved in the creation of a work they commission,’ says Rees.

‘For illustration clients that use stock illustration and photography, AI-generated imagery will offer another appealing, low-cost alternative on the “technological fast-food” menu, ranging from the sublime to the slime.’

Mucho’s 2024 campaign for biotech company Spora, a company that makes mycelium- based fashion materials. AI-generated compositions explore mushrooms, textiles, transformation and regeneration, while the colours were inspired by Chilean Patagonia.

Part of the process

Bisat Marshall is less engaged in the difficult questions surrounding AI image generation. ‘The discussions focus on the image as outcome,’ he notes, ‘but images aren’t the end point of my process, they’re part of it. AI can’t design. Any production designer that doesn’t understand that their job is to tell stories is already fighting a losing battle. It’s a tool whose output is as good as the user’s knowledge of visual culture and their ability to edit.’

For London 3D studio Fromm, such tools are also part of the process. Fromm’s Vince Ibay and Jessica Miller use DeepMotion to take movement from video footage and transfer it as an animation to a 3D model, such as the creepily twerking figures they made for TV show The Secret Lives of Mormon Wives, and their funny, unsettling illustrations for The New York Times and Bloomberg Businessweek. ‘The results need cleaning up as they usually come out very rough,’ says Ibay, who attended the same creative computing course as Field’s Jann Choy, ‘but they make a good starting point for 3D animation.’

Many designers appear to be using AI tools like an assistant (or ‘co-pilot’, to adopt Microsoft’s disingenuous term), but there is little consensus about the ways in which the tools help the creative and artisanal process of bringing a project into being.

Studio Blup’s Dines (see Eye 100) describes using Midjourney for a pitch to promote a new version of Elton John’s Diamonds. ‘The idea was to create this “diamondesque” approach,’ says Dines. ‘We created this bust and put it into the middle of a room, and then behind it you have these digital screens. And then we then have it in this weird room with the big diamond “E” – you walk through the wall and all of a sudden you are in Elton’s space with a piano.’ At this point he found that Midjourney could never get the ‘E’ right. ‘It’s so bad. Even if I tried to explain that it was like an “E” with a star in it, they’re like, nah, what are you on about, Dines? In the end the client liked the simple idea we made by hand because it was easier to create it on a 3D program than keep trying to prompt it!’

Verònica Fuerte of Hey Studio has been experimenting with AI illustrations that she posts on her Instagram ‘play’ account @wonderlandbyhey. (See opening spread.) These include colourful flowers, patterns, whimsical interiors and characters with cute faces you could imagine fronting a consumer ad campaign. For client work, ‘it’s more to generate visual ideas, maybe mock up ideas we have in mind so that we can make it super quick to visualise the concept … not something final,’ she says. She followed this approach in Hey’s identity design for artisan cheese shop Can Luc in Barcelona, partly for speed, partly to keep within the limited budget, but there is no AI imagery visible in the final job, with its staff aprons and hand-painted sign over the door.

Elsewhere in Barcelona, Mucho’s Marc Català puts forward a nuanced view. ‘I relate to Marian Bantjes’ experience. AI is still much more hard work than it seems. It does save time in terms of the production of a final image that would take up a lot of production cost, effort and time. But not so much in the production of the sketch of that image, which is the part of the process in which designers are involved. AI does not save time if you have something specific “in mind”. I have spent hours trying to get it to do what I want it to do to no avail, and would have got those results faster through other techniques, or with other people’s help. The value is more in the serendipity of the results I can select from. I have found some crazy results that feel amazing.’

Català quotes the influential Spanish intellectual and ‘digital transformation expert’ Genís Roca, who wrote: ‘In paleontology, we measure revolutions in tens of thousands of years. My parents were still living the consequences of the agricultural revolution. When clients come to me stressed about digital transformation I tell them to calm down.’

Two recent Mucho projects, Máxima and Spora, made effective use of Midjourney images: in the former, the images of flowers after full bloom changing into their ‘mature’ stage; in the latter, some ‘impossible’ organic mushroom-like structures.

Català’s colleague Pablo Juncadella says: ‘While AI might seem like a tool tailored for the young, it is better suited to those with the most experience and expertise. The results of visual exploration are always better in the hands of someone with an understanding of lighting, the history of photography, composition, design, the humanities, visual culture or art.’

Photographer / artist Phillip Toledano offers another interpretation of ‘co-pilot’ or assistant: ‘My analogy has always been, it’s like working with a very, very creative, talented, very drunk person. It’s like this person’s sort of shit-faced, but a genius.’

As with Rankin’s F(AI)KE photos, Toledano knowingly challenges our ideas of true or false. He acknowledges that many of these counterfeit images are more convincing when they are quite small, on our phones. The colour prints of his Another America project play on shared nostalgia for urban photography; We Are At War cleverly fakes and recreates the reportage work of Robert Capa, a war photographer known to have self-mythologised without recourse to technology. But Capa, for all his later slipperyness, genuinely shot film on the Normandy beaches. Toledano says with a smile: ‘I have the benefit of sitting around at home in my dressing gown, making extraordinary war photography, versus actually being under fire in the field.’ (See ‘Phoney war’, pp.58-60.)

In this collaboration with US tech specialist Look Mister, Studio Blup trained a custom AI model, Flux, using 30 unreleased visuals from the Blup library to emulate the studio’s signature aesthetic.

How will machines reward humans?

Sebastian Koseda has been immersed in the topic for a while, working with many clients and collaborators that have machine learning at their core. ‘Technological development has always propelled the creative industries forward,’ he says. ‘The chisel, the Jacquard loom, letterpress, the Macintosh and now AI – all radical developments in communication and new ways for people to express themselves. AI has already created new jobs and there are more coming – prompt engineers are in high demand. We may have always been “prompt engineers”, the process has just become faster and more intuitive. Is it so bad if AI starts designing our banner campaigns?’

Koseda mentions the possibilities of blockchain in relation to AI. In contrast to Nightshade’s quest to defensively scramble the metadata, the ingenious project Yaya Labs asks: ‘How will machines reward humans?’ Its answer is an ecosystem that ‘secures and monetises content on the blockchain’. Koseda, lead designer on this project along with Ben Ditto, explains the idea as follows:

‘The creator uploads everything they wish to monetise. Their work is then secured on the blockchain and used for training data (or sold as part of data packs). Everyone in the “Yaya Community” can then monetise their work and input, ensuring everyone in the chain is paid for their contribution.’

Koseda was also the creative consultant on DeepMind’s Visualising AI, commissioning artists from around the world to create ‘more diverse and accessible representations of AI’. The resulting illustrations (by Champ Panupong Techawongthawon, Martina Stiftinger, Nidia Dias, Tim West and others) conceptualise ways that AI might be used in different sectors.

‘Whenever you typed “AI” into a stock image site you would be served a white robot shaking hands with a businessman surrounded by blue matrix code or some permutation of this. We were asked to help define the visual landscape for AI by creating a royalty-free bank of images. We realised it would be impossible to create these using AI – Midjourney couldn’t create something remotely new that wasn’t referencing what was already out there. So instead of getting AI to describe itself visually, we worked with a spectrum of wildly talented human artists and animators to create an extensive library available for free on Unsplash.’

Stock illustration libraries are starting to offer AI options. Shutterstock apparently avoids copyright issues by developing ‘ethical AI systems’ with files modelled on images already in its collection, thus remunerating its artists. The new Getty / Nvidia collaboration promises something similar, a direction welcomed by editorial designers such as Telegraph Media Group creative director Kuchar Swara. ‘This is exciting because companies are indemnified against copyright issues,’ he says.

‘I am excited by AI as a tool … Midjourney has been exceptional, but we are not allowed to deploy it. Adobe is not bad for things like retouching or cutout work to make things look premium. Poorly lit pack shots supplied by different firms can be spruced up and unified. We do not have the resources to shoot every product, so this service has been a life-saver and will be used for a business initiative called “Recommended”.’

Graphic designer Dylan Kendle, formerly of Tomato, has found text-to-image generators (Wombo Dream, Midjourney, Adobe Firefly, Stable Diffusion) fun to explore. ‘It’s the mistakes that most interest me, the liminal stages between intent and execution. This is fortunate as AI makes of a lot of mistakes. As Marian Bantjes points out, they’re like a one-armed bandit. They’re like a silent (sometimes) compliant partner.’ Kendle has been using them for personal work and R&D, and for a music project: Ben Chatwin’s ‘Verdigris’.

‘I can see the upsides from my position [but] the downsides are manifold, and not merely confined to the creative “act”,’ he says. ‘We’re training models on a vast image bank full of similar (and often retouched) images; prompts referencing specific artists or real people pose intellectual property (IP) and ethical dilemmas; and there are significant impacts on a creative workforce without even considering the environmental effects of oversized data centres.

‘There’s already an impact further downstream as machine learning strips billable hours out of creative supply chains. The creative potential is huge, but so are the financial drivers. Given there’s no union, it feels like it needs a legal framework alongside good leadership and considered corporate positions on its use.’

Studio Blup’s Dines recalls being anti-AI at the beginning, but has used it to emulate his own aesthetic for US tech company Look Mister. Dines says: ‘It’s about honesty and understanding where you have got these ideas from and not trying to blag it. You can’t kid a kidder, you know what I mean? If you are not sharpening your tools on your programs and you’re just prompting, then what are you becoming? What is your purpose in life? If you’re not creating with your hands and your mind and you’re just typing and you’re proud of this prompt that’s come out a machine (and you put on high res), that’s going to die soon. And then it’s going to be too late. You can’t go back because you haven’t practised in two years. You’ve been too busy writing prompts!’

Oswin Tickler, a designer, coder and teacher, says: ‘The universities are playing catch-up because AI has become such a seemingly dominant part of the media and communication landscape in a short space of time. We haven’t got people in place that can teach it from the standpoint of practice. Most people haven’t yet got their heads around it.’

Tickler is positive about some AI programs’ ability to help with Open Source programming. ‘All the data is there to scrape and there are strong Open Source communities where they’re sharing all the stuff. For me it’s great because I can “see under the hood”, whereas with a purely text-to-image program, you’re not in control. So it feels like the “infinite monkey fear”, just bashing away at keys. Some of it is wild and there are so many options, but it’s easy to get distracted because there’s just so much choice and you could just end up with a lot of very mediocre looking AI-generated stuff.’

Steven Ryan (of Chicago design practice Substance) used the AI app Runway on a promotional video for financial services company Morningstar. The video shows each individual getting older (from 25 to 80).

Environmental spectre at the AI feast

Though environmental concerns underpin current discussions about AI, few designers brought up the issue until I mentioned it – though some noted how hot their laptops became when AI programs were running.

Silicon Valley is full of experts who pour scorn on activists’ questions about AI’s power consumption. Google’s Eric Schmidt has argued that, despite AI’s energy demands, he would rather bet on AI solving the problem than try to constrain AI: ‘We’re not going to hit the climate goals anyway because we are not organised … I’d rather bet on AI solving the problem than constraining it.’ To which scientist Gary Marcus (author of Taming Silicon Valley) responded: ‘We shouldn’t place massive bets like these without transparency and accountability … Society has to have a vote here.’

‘Personally, I have a challenge ethically in how much to rely on AI, from the artistic exploitation angle and from the carbon consumption angle,’ says Span’s John Pobojewski. ‘The carbon impact is well documented, and while life today is inherently reliant on persistent data centre processing, this new “fancy tool” has an unquestionable and tremendous thirst for power usage. Definitely makes me think twice before firing up Midjourney or ChatGPT.’

‘The power-intensive carbon implications are another thing entirely,’ says Michael Johnson. ‘A tonne of people are using ChatGPT as their “writer of a first draft”, and I bet very few think through the environmental implications.’

A recent Harvard paper shows that many US data centres are in coal-producing regions such as Virginia where the ‘carbon intensity’ of energy used is 48 per cent higher than the US national average. One of the paper’s authors points out that emissions will jump as users ‘scale up’ to the file sizes required for images and video.

UE’s Gethin Lewis considers the environmental spectre at the AI feast: ‘Water, energy, all these other precious resources that we’re undoubtedly going to be having less and less of in the future – this is something that needs to be discussed and considered. I love these machine-learning tools because they allow people to experiment with things in a new and interesting way. But then there’s the writer who said “give me a pencil and a paper and put me up against a room of a hundred people with computers and I’ll out-create everyone in there.” Which [is a principle] we follow at UE – draw to express yourself in a non-verbal way. Then you can surprise yourself … get to things that you can’t get to by talking about them because you can do things that are nonverbal.’

The AI tools we use are often opaque, ‘black box’ technologies, heavily subsidised by venture capitalists betting on Highlander-style battles between tech Leviathans. Policy researcher Miles Brundage (formerly of OpenAI) worries that ‘only a tiny fraction of the industry’s talent is applied towards making [AI] safe and secure …’ For Pum Lefebure, ‘If we are the “moms” of AI then we have to be responsible!’

In a post on Blood in the Machine, Brian Merchant attacked the use of the term ‘democracy’ by OpenAI’s CTO, Mira Murati. ‘AI will not democratise creativity, it will let corporations squeeze creative labour, capitalise on the works that creatives have already made, and send any profits upstream, to Silicon Valley tech companies where power and influence will concentrate in an ever-smaller number of hands. Artists … get zero opportunities for meaningful consent or input into any of the above events.’

Big tech corporations are also using complex accounting techniques to distract from the surge in emissions produced as they (in the words of the Financial Times) ‘race to develop power-hungry artificial intelligence, potentially threatening their commitments to net zero.’

Is our use of machine learning, through these costly new tools, shaping up to be as regrettable as heroin or asbestos, or as quaint as a zoetrope? Or are they more like the internal combustion engine or antibiotics: something that will change the world so much it may become impossible to imagine life without them? Digital pioneer Erik Adigard says: ‘The alchemy of AI imagery is a bloody arena where the seductive, the assaultive, the derivative, the historic and the fake are battling for our choices.’

Yet as Mucho’s Català points out, humans change slowly: the adoption of AI may take generations. Machines did not make drums obsolete, but they changed music. Attitudes evolve in relation to ‘old’ technology. Machine learning is a long game, and there are many bubbles and punctures to come while we marvel at the fireworks and deal with the bin-fires.

No AI was used in the writing and editing of this article, apart from transcription service Rev.com.

First published in Eye no. 107 vol. 27, 2025

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.