Autumn 1993

Way out west

The work of recent Cranbrook graduate Martin Venezky indicates new directions at the accademy

Martin J. Venezky who graduated from Cranbrook Academy of Art this summer, is one of the latest in a long line of mature students to use his time there to take stock of his career and refresh his approach. The way in which Venezky’s work builds on recent Cranbrook preoccupations, while extending its enquiry into new areas, suggests that the controversial academy (see Eye no. 3 vol. 2) maintains its position in the vanguard of exploratory graphic design. Venezky recently followed another Cranbrook tradition by completing an internship at Studio Dumbar in the Hague

Venezky, now 36, studied fine art at Dartmouth College, New Hampshire, graduating in 1979. he did routine design work in Washington before moving in the mid-1980s to San Francisco, where he worked in the design department of a marketing group. During this time he became aware of New Wave innovators such as Tom Bonauro and began to explore design history for the first time. He felt frustrated that there was no way of importing a freer sensibility into his own work.

Venezky first applied to Cranbrook in 1981; he was accepted, but decided not to go. It was the publication of Cranbrook design: The New Discourse in 1990 - ‘the work baffled and surprised me’ - that convinced him this was where he should be. At course leader Katherine McCoy’s suggestion, he followed his early student outings in the vernacular with a more personal, even autobiographical approach. He began to write and receive strong encouragement with the arrival in his second year of the poet Brian Schorn. For several of the students, the focus had switched from literary theory - an establishment of interest at Cranbrook - to the living matter of literature itself, and how it might be related to design. A course of reading in phenomenology, the description of conscious experience, confirmed Venezky’s desire to explore ‘what it feels like to be human’ in his work.

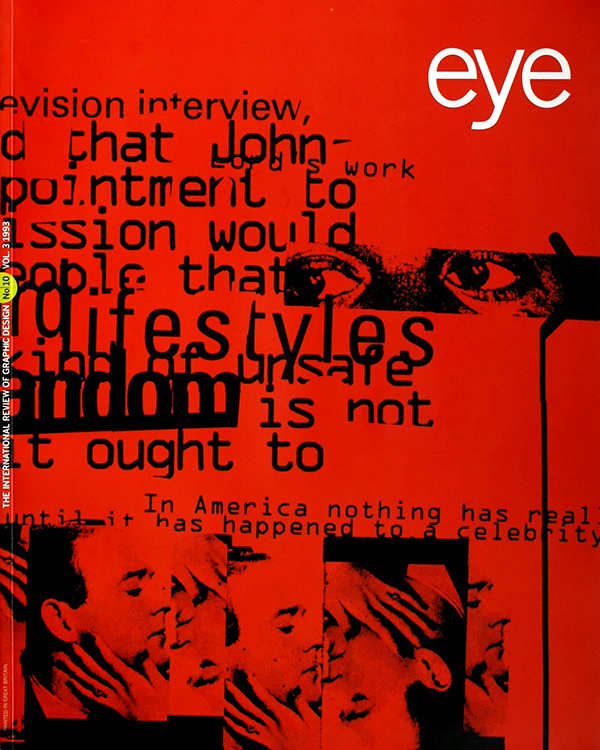

To the casual observer, Venezky’s Cranbrook projects might appear to exhibit all the hallmarks of computer-driven deconstruction. But his work is about neither theory nor technology. Its gestural vigour is, if anything, a reaction to the computer’s dead hand. In a first year project based on Magic Johnson’s announcement that he has AIDS, Venezky used a Macintosh to generate typographic material, then cut and spliced the output manually. A staccato rhythm judders across the resulting word-picture, locking the type and multiple ‘kissing’ heads in a jittery embrace. Venezky’s essay ‘What I know about photography’ (which went on, in a pure text version , to win the Pentagram Prize) wrests equally intense emotion from the discarded snapshots and album portraits blown up way beyond their original sizes. Once again, the work is a reaction to what he sees is the aridity of theory, in this case photographic.

In Venezky’s major project, loosely titled ‘ Notes on the west’, his experiments in design, writing and photography converge in 12 panels exploring the mythology, symbolism and continuing history of the cowboy. In preparation, Venezky read long-neglected nineteenth-century novels, twentieth-century gunslinger pulps and histories of the west, sat through 30 or more big-screen horse operas, and travelled the west taking pictures. The cowboy, he points out, was once an abiding figure in the American boy’s childhood, including his own. the earliest photograph of his father shows his brandishing a six-shooter. In the early mythology of the west, notes Venezky, the cowboy stood for a code of ethics and the ‘unwritten law’; all that is left today is nostalgia.

‘I look at the landscape and I don’t understand what it means anymore,’ he says. ‘MY west is based on language and symbol.’ A screen made from hand- tooled leather patterns obscures the mountains; or the land is seen in disconnected detail from behind the wheel of a speeding car. The gaps in a prairie fence conceal - what? - a background of blurs. ‘When you think of the west,’ says Venezky, ‘there are all kinds of filters that tell you how to look at it - what you are supposed to see and not see.’ As, for instance, when a cowboy poses naked except for stetson, pistols, shorts and boots. The image may strike us as funny now, but to gay readers of physique magazines in the 1950s or early 1960s it would have been tantalising. Its juxtaposition with the cowboy practising a rope trick is a wonderful touch.

First published in Eye no. 10 vol. 3, 1993

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.