Winter 2025

Where the wild type is

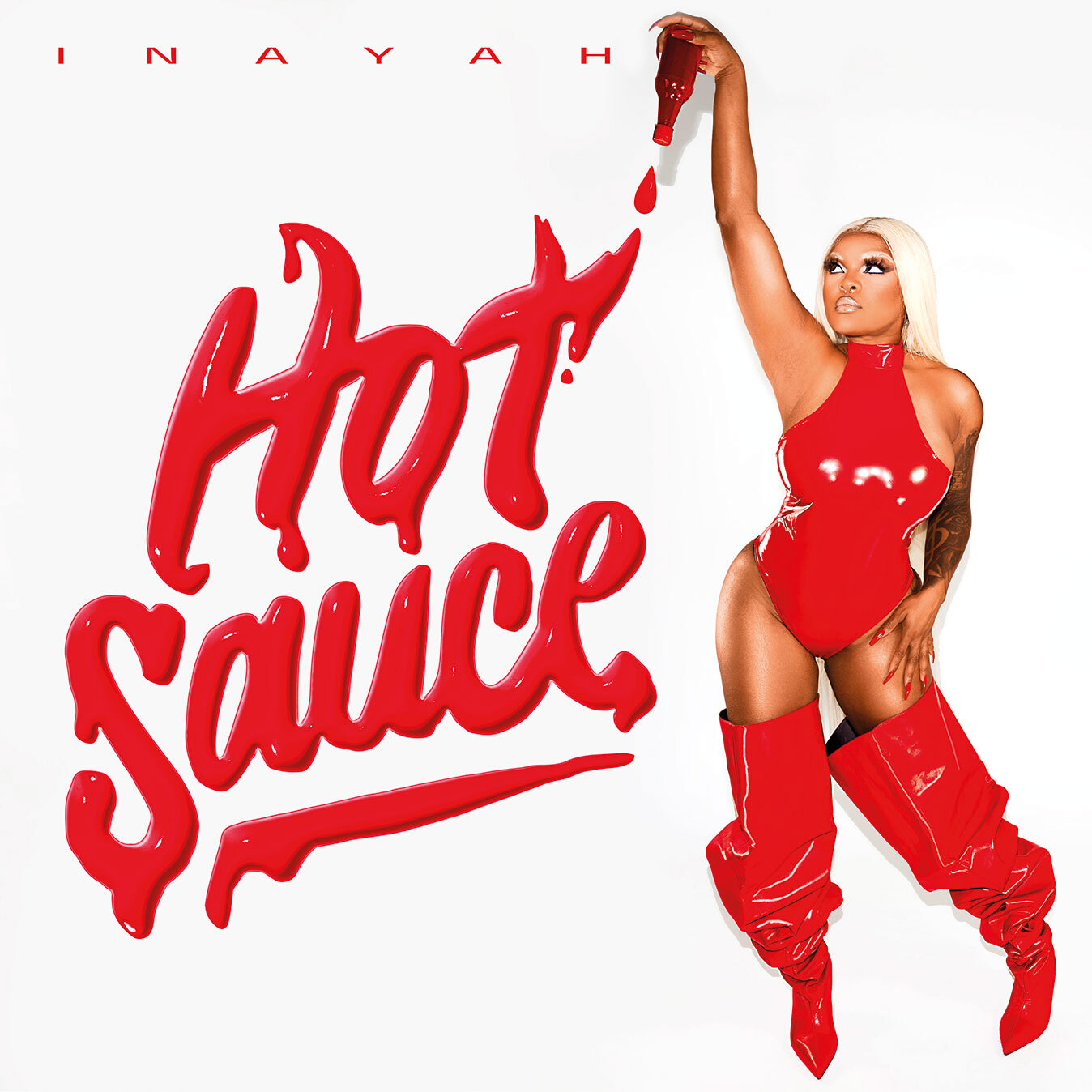

Working across record covers, logos, merchandise and stage design, Amaya Segura brings innovative typography to contemporary R&B, hip-hop and beyond. Interview by Holly Catford [EXTRACT]

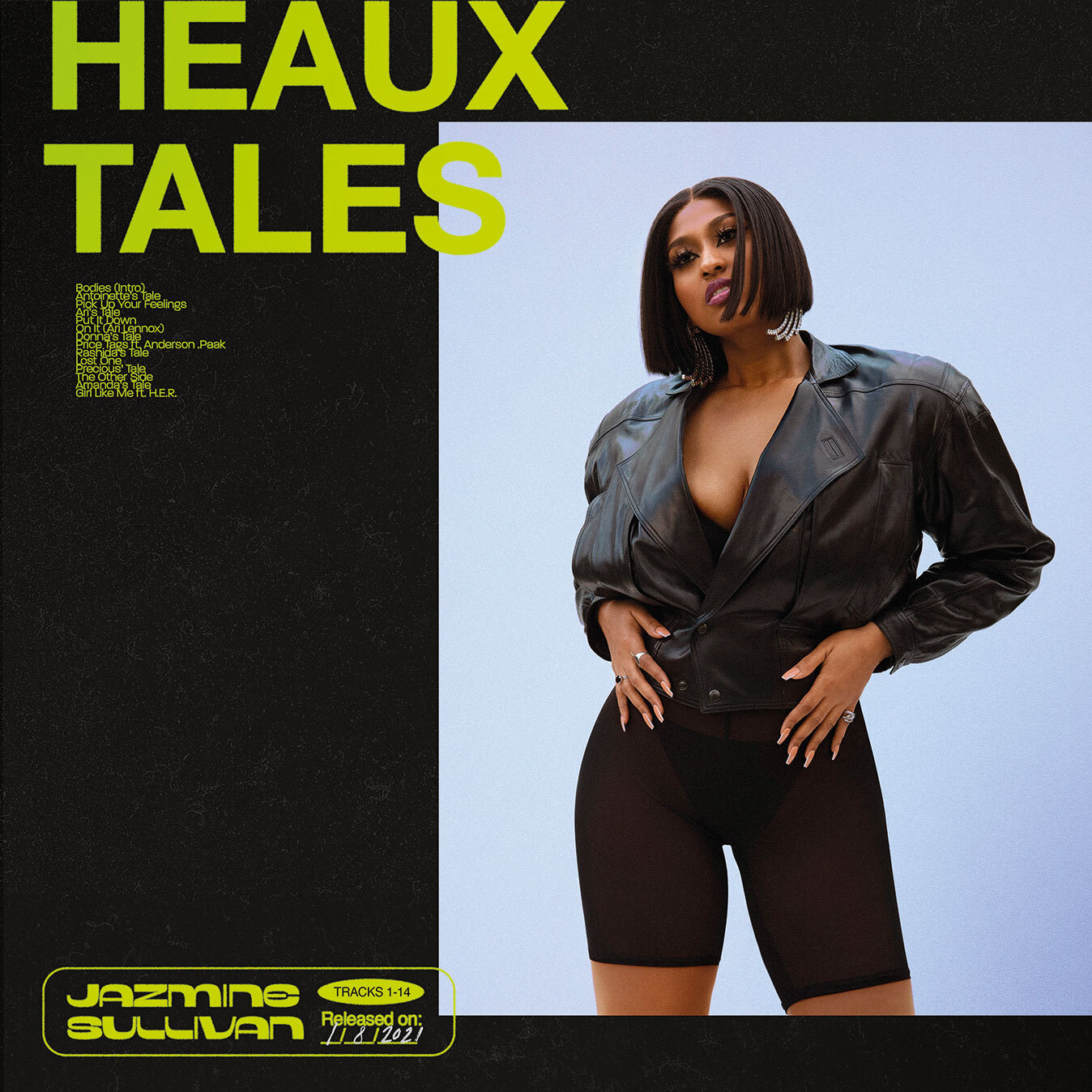

When I stumbled across Amaya Segura’s Instagram feed (@epistolare) I was instantly excited. Segura has had a hand in most of the recent records I have loved, both in terms of design and music. Contemporary R&B artists such as SZA, Jazmine Sullivan, H.E.R and Giveon all have their sights set on the future, with one toe still dipped in a classic R&B sound. This is what Segura references so incredibly well in her work for them. She produces work that is sited in the now.

[…]

Holly Catford: Amaya, you tend to use common classic typefaces such as Helvetica and Georgia within the R&B/hip-hop arena, using them out of their normal context, as with Jazmine Sullivan and the newer Coco Jones cover. When did you start doing that?

Amaya Segura: It’s a skill born of necessity, in the sense that really a big thing about creating art for labels is understanding that you need to be able to clear every single font you use legally.

I started

taking the bones, these typefaces as the bones of things, and either giving

them an alignment or a placement or a treatment that really makes them edgy.

With Helvetica, it’s one of those fonts that can be completely contemporary if

you use it in the right way. It can also be completely bland and authoritative.

It’s placement

and colouring that take it to that place. Helvetica was one that didn’t need a

lot of tweaking, but with a font like Georgia, it was about, okay, what are the

pieces, the bones of Georgia I can start using?

What I really liked about that font for Giveon was that it was rounded but sharp. I needed something that had that duality of like, yeah, it’s smooth, it’s silky, but it’s not too friendly.

It’s like his music, isn’t it?

Exactly. It needed to have some edge to it. Looking at the typefaces, this one has the right ratio of serif to curve. A smooth curve on the ‘G’, which I modified to death, but it was a good bone. I’m looking for a typeface that has the right curves and shapes that I can modify to where I need it to go.

Sinéad’s typeface is based on the bones of a heavily modified Helvetica. I cut it up, chopped it into pieces and went on reforming it.

And I drew the Thai letters right under it. So I would draw a piece of the Thai letters and see which pieces of the Helvetica would fit with it so that I could reassemble it like a puzzle.

How did you get into design for music? How did you get to where you are now?

I was trying to find a place where writing and illustration met. In a past life, I thought I was going to become a linguistic anthropologist. I have always been curious about language and there’s so much of our culture that gets transposed subtly into the language. That’s true for graphic design, too. You start in a different way: in linguistic anthropology you depend on phonetics and cultural connotations, while in graphic design, it’s almost like the next level, because you have to learn to communicate to a specific audience …

Holly Catford, designer, publisher, Bristol

Read the full version in Eye no. 107 vol. 27, 2025

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.