Summer 2008

Adrien Pelletier

Who cares about graphic design history?

Adrien Pelletier was born in Paris and graduated from Central Saint Martins, London, in 2004, and gained an MA from the Royal College of Art in 2006.

Q1. What do you think is meant by ‘the canon of graphic design history’? Do you buy design history publications?

A1. ‘The canon’ doesn’t mean much to me: to make sense, it would have to be plural. ‘The canons of graphic design’, then, are a series of works that are each considered to be the most representative or the best of a particular form, genre or culture. I would prefer the word ‘epitome’ (a short concentrated expression of something, a typical example, a personification.). To me, ‘epitome’ seems more appropriate, in the sense that a ‘canon’ serves as a model, a priori, whereas the ‘epitome’ of something comes a posteriori. So when one looks back, one can say, this work encapsulates that moment (it didn’t define the moment).

Now, calling anything ‘the most representative’ or ‘the best’ has to be challenged, argued. What makes something ‘iconic’ is an interesting and problematic question. Issues of authority, power and discourse are inevitably at stake, as well as issues of quality, novelty and trends. Even the word ‘epitome’ raises ontological questions, as it is supposed to be a ‘concentrate’ of something, supposing that there is an essence.

So, in the end, if I were to comment on some examples of graphic design, I would just say ‘a selection of great works’, which is a bit less authoritative as a position, as it suggests a subjective appreciation (or does it?).

The reasons why there is a (relative) consensus over the excellence of some works should be examined, as well as the conditions of access to the status of ‘classic’, or visual landmark. If there is a history of graphic design, there is a need for a sociology and a historiology. And I do buy design history publications, but I don’t always read them.

Q2. Does design history have relevance to your design practice?

A2. My generation of designers is quite geeky and often comfortable with quoting and visual sampling. If we loosely share a common ‘graphic culture’ we all strongly relate to pop culture and explore different aspects of it. Many of us quote existing designs, classic or obscure. Some of these hommages, parodies, spin-offs, are relevant (although in a so-called post-critical environment, the concept of ‘relevance’ needs to be challenged, too). Others have more to do with a ‘retro’ fetish, a bit indulgent and gimmicky. And that’s fine, too.

Q3. Where did you learn design history?

A3. Mostly in France, at the Ecole Estienne in Paris, where design history was taken a bit more seriously than in any other places I studied.

We had a fantastic tutor, Mr Baudry, who taught history of art and design and semiotics, and made everything sounds so exciting. He once cried out of emotion, talking about Gerrit Rietveld, I think. A bit hysterical, but he got us hooked. What was great was his ability to ‘relink’ designs to their context and translate them in terms of solutions to – or manifestations of – problems particular to a given time. He had both a chronological and transversal approach.

Also, we had workshops during which we would ‘play’ with the ideas and notions we had been studying. Most of it consisted in extending existing works in a different direction, or responding to them, or translating them into something else. That was a smart way to engage theory into practice. He made us write 3D dissertations, too. I wish I still had this theoretical stimulation now.

Q4. Is history relevant to the new technology and techniques you have had to master in your work?

A4. Absolutely. These ‘new’ technologies and techniques are part of history too. I mean, they are history, as the history of graphic design requires a certain understanding of the continuum and the discontinuities in technology. What I use today is here for a reason, in a particular state, and if I don’t grasp this, how can I push things forward?

Q5. If you were in charge of a design education programme, what aspects of design history would you teach to your students?

A5. I’d try to cover as many aspects as possible. Actors, context, techniques, trends, cultural politics. Even economics. (Some advertising people are still struggling with the idea that the 1980s are well over.) I’d get different people to cover some of these. As many perspectives as possible, and as diverse as possible. It should be a daily practice. Like a warm-up, in the morning. People who think students could be harmed by ‘overexposure’ to overwhelming amounts of great creativity are either very cynical, or stupid.

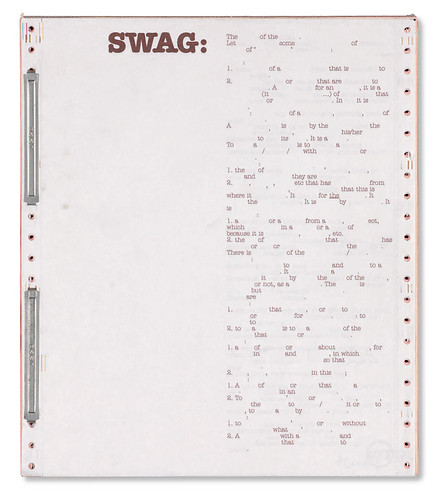

Top: cover from ‘SWAG: The Talent of the Others’ BA dissertation by Adrien Pelletier, Central Saint Martins, 2004. ‘This home-prited book is a collection of fictional interviews around the theme of “borrowing from others”,’ writes Pelletier. ‘The research investigates various dialectic oppositions, such as original vs copy, authentic vs fake, author vs artist, legal vs legitimate and authority vs integrity. And, of course, you vs me.’

First published in Eye no. 68 vol. 17 2008

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.