Summer 2008

Barbara Ehrbar

Who cares about graphic design history?

Barbara Ehrbar comes from Biel/Bienne, a small bilingual town in Switzerland, where she now works, and graduated from the Ecole cantonale d’art de Lausanne (ECAL), Lausanne, Switzerland, in 1999.

Q1. What do you think is meant by ‘the canon of graphic design history’? Do you buy design history publications?

A1. To me, a canon is the shifted repetition of a song over and over again. A song has a beginning and an end – maybe that song / list of names should be extended with other names? Maybe the interesting part of the canon is where two notes overlap and make harmonies.

I started buying graphic design books about ten years ago. It’s a pretty nice collection today. I mostly buy contemporary design books – the books that were contemporary ten years ago are already history. I also have books about Josef Müller-Brockmann, Wolfgang Weingart and the Bauhaus.

Q2. Does this kind of design history have relevance to what you do in your design practice?

A2. Of course. It’s like the canon: the base for all voices is the same song. These pieces of design are the base for all the future design generations. They formed our habits of viewing and perception, but I rarely look for inspiration in the past. Maybe I should start doing that. I’ve started being bored by graphic design these days. New things are rare.

Q3. Where did you learn design history?

A3. I never had design history classes. At ECAL I skipped the first two years of the five-year design programme, and design history was in year two. I was there at the beginning of the Pierre Keller era, and we had workshops with people such as Laurie Makela, M/M (Paris), Cornel Windlin, etc., the young guns of the time. We never looked back.

Later, at the School of Visual Arts (SVA) in New York, I had my first class about design history with Steven Heller. It took me a while to understand his fascination. I remember him being surprised at the gaps in my knowledge and education.

Q4. Does history have any relevance to the new technology and techniques you’ve had to master in your work?

A4. I am part of the design generation that grew up with a computer. I’ve always designed on a computer. I have never set type by hand. I do a lot of jobs by hand but they all end up as digital files.

Q5. If you were in charge of a design education programme, what aspects of design history would you teach?

A5. I don’t know if it is possible to teach graphic design. It is like art and music. You can teach how to use Photoshop, the rules of microtypography or how printing works, but I don’t think that getting a sense for visual ideas happens in a design class.

During my time at ECAL we were just surrounded by very inspiring people, books and work. Nobody told us to do things like this or like that. I’m pretty sure that it is possible to become a good graphic designer by looking at tons of publications about great designers’ work, so there should also be work from the past.

The most fascinating aspect that relates to design history is that graphic design can be a powerful tool. The graphic designer is able to influence his or her audience. Graphic design can make (political) opinions. I would teach students to be aware of this and play with it.

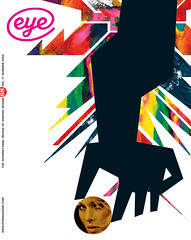

Top: Poster for the summer school programme at the Kunsthaus, Zurich. Design and photograph: Barbara Ehrbar, Superbüro, 2006.

First published in Eye no. 68 vol. 17 2008

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.