Friday, 3:00pm

23 March 2018

Colour field

By choosing colour over black-and-white, Joel Meyerowitz pioneered a new type of American street photography. Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for Eyemagazine.com

Joel Meyerowitz, now 80, belongs to a select, roving band of American photographers who rejected black-and-white in favour of colour. This might seem unremarkable now; if colour was available, then why not use it? But in the 1960s, it was still deemed too blatantly commercial by serious photographers, though Meyerowitz says he knew nothing about that embargo when he started. He carried two cameras, loaded with each kind of film, and would try to shoot the same scene twice, so he could make a comparison later. In his career survey, Where I Find Myself (Laurence King), he shows a series of pictures exploring the differences.

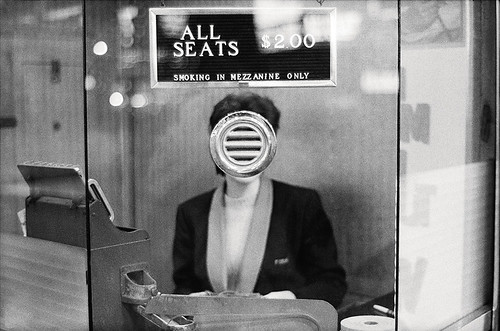

For Meyerowitz, colour images simply have more information in them. In two similar shots of a man in a belted raincoat looking out over a landscaped garden, the Magritte-like pose is slightly better in the black-and-white version. Even so, Meyerowitz favours the ‘fuller description’ of the scene in the colour shot – and with the selection of images he offers, one can see his point. For the kind of jazzy, thronged and eventful street picture that he wanted to make, colour worked best. For all their promise, Meyerowitz’s earliest black-and-white pictures are still in thrall to the influences he cites most frequently, Robert Frank and Henri Cartier-Bresson. In The Americans, Frank has a perfect shot of a musician whose head is entirely obscured by the bell of his tuba. In 1963, Meyerowitz made the same head-replacement gag with a woman behind a round speaking grille selling tickets at a movie theatre.

New York City, 1963.

Top: New York City, 1978.

New York City, 1963.

Meyerowitz was working as an art director at an advertising agency when he saw Frank weaving around two girls he was shooting for a campaign. ‘It opened up the idea that one could move and shoot at the same time,’ Meyerowitz writes. He returned to the agency determined to become a photographer. In Where I Find Myself, he recounts his life story in reverse, starting in the present, with the detail of how he began coming at the end. The device works well enough visually and prevents his later work seeming like an afterthought, though I preferred to read from back to front. Meyerowitz is a charismatic raconteur and guide on film (see his contributions to ‘The Genius of Photography’ TV series and Joel Meyerowitz: Sense of Time, 2014) and his writing has the same voice – humane, affable and enthused.

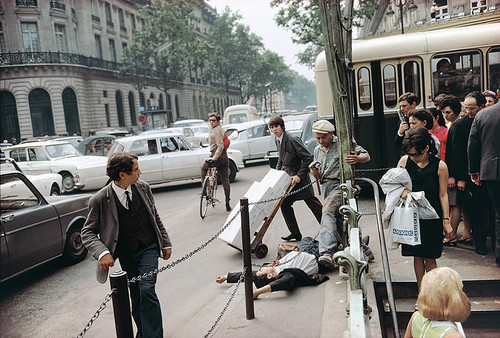

Paris, France, 1967.

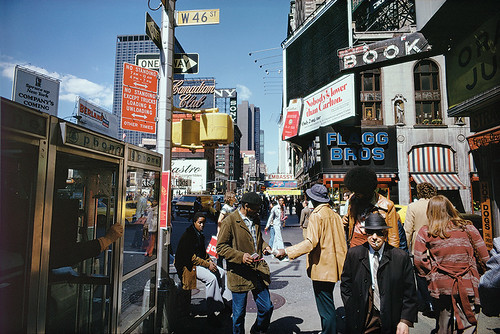

Meyerowitz’s street pictures reached their apogee in the mid-1970s. The slower speed of colour film meant the depth of field was shallower. He wanted everything to be in focus and that required stepping back from his usual eight feet from the subject to twenty feet, but at that distance it was no longer possible to isolate single incidents, as he was used to doing. After initial misgivings about the openness of these street panoramas, he hit upon the term ‘field photographs’; New York City, 1976, shown as a double-page spread, is a superb example. Seething with energy, the shot captures dozens of disconnected figures, near and far, under a multi-coloured canopy of shop fronts, advertising billboards and street signs. The scene cannot be taken in at a glance because there is no centre of attention, no self-evident ‘story’. The more one scans this dense, non-hierarchical field of urban events, the more the image divulges.

New York City, 1976.

By this time Meyerowitz was on the cusp of a new direction. He began to work with a large-format view camera. Where before, with a handheld camera, he could move around freely, sometimes without his subjects realising he was there, now he was always visible. View cameras impose stillness and formality on an image’s design and Meyerowitz’s pictures tend to be of places and things rather than people. He made a beautiful series of pools by the sea in Florida and atmospheric studies of water, sky and the horizon in Massachusetts. A sensitive, early 1980s series of portraits of young people photographed on the beach anticipates the work, a decade later, of Rineke Dijkstra.

Florida, 1978.

For a while, Meyerowitz experimented with panoramic beach pictures composed of three carefully matched shots, but he shied away from the ‘directorial’ mode, he says, ‘perhaps because I was locked into the aesthetic of the street and my moral sense of not tampering with reality.’ Back then, he thought this kind of picture was a dead end and he could find no rationale for carrying on. Now he realises – one senses a little ruefully – that it was a new departure that would soon be pursued by others.

Meyerowitz lives in Tuscany these days and his most recent photographs are still lifes, featuring objects once owned by the painters Cézanne and Morandi. They have the exacting attention to every particle in the frame that has always distinguished his pictures. For lovers of street photography – a genre he feels the omnipresent mobile phone has de-energised – he remains a master, and the book showcases these classic images on generous pages with high-octane impact.

Eddie, a mechanic, standing by a grappler, New York City, 2002.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.