Monday, 7:00am

28 November 2016

Elton John's new vision

The Radical Eye: Modernist Photography from the Sir Elton John Collection

Tate Modern, until 7 May 2017‘The Radical Eye’, the superstar’s opulently framed collection of modernist photography, is a revelation. Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for eyemagazine.com.

Let’s acknowledge at once that ‘The Radical Eye’ is a blast of pure pleasure for the eyes and a show that no admirer of modernist photography will want to miss. The ‘new vision’ that flowered in the 1920s is closely entwined with the growth of the new graphic design during those years and its visual inventions are inscribed to this day somewhere deep in the profession’s DNA. ‘The Radical Eye’ is a wonderfully engaging history lesson and while it contains a smattering of celebrated masterpieces, as one would expect of such a survey, it also includes numerous lesser-known pictures that are just as deserving of attention as the textbook classics.

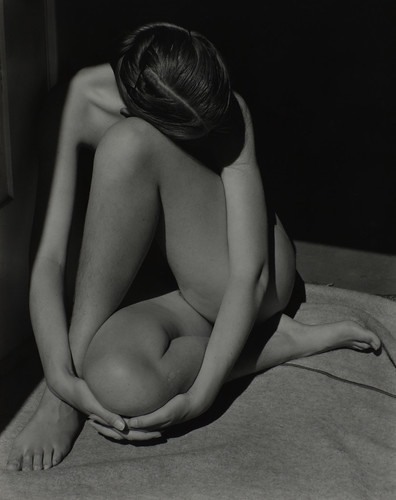

Edward Weston (1886-1958), Nude, 1936. © 1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents.

Top: Man Ray (1890-1976), Glass Tears, 1932. © Man Ray Trust/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2016. All photographs courtesy the Sir Elton John Photography Collection.

It is common for shows of this kind to be based on private collections, but ‘The Radical Eye’ is something else again. The pictures come from the treasure chest of Elton John and, unlike exhibitions where the wealthy collector’s unfamiliar name may barely register, the flamboyant pop star’s persona and highly resourced zeal as a collector permeate the show. Tate Modern tries to strike a dignified balance, but the exhibition depends on John’s largesse, and his star power is potentially a big draw for the gallery. The singer hopes the images will enthral those who know nothing about photography in the way they first enthralled him.

John admits he knew nothing about the history of photography until 1990. He had just finished drying out in rehab when an LA gallery owner showed him pictures by Horst P. Horst, Irving Penn and Herb Ritts. John immediately bought twelve prints and a new ‘addiction’ took hold. Today, he has 8000 photographs, which he houses in an 18,000 square foot apartment in Atlanta, where he employs a director to look after the collection. The exhibition opens with Man Ray’s Noire et Blanche (1926), a shot of a woman’s face and a mask in positive and negative, which hangs above John’s bed, and there is a grid of nine small pictures normally found in his office. In the apartment he shares with David Furnish, the photos are packed so tightly the frames almost touch and they cram the walls from floor to ceiling.

Installation view of ‘The Radical Eye’ with many frames used by Elton John for his collection of Modernist photographs. Photos: Tate Photography, 2016.

I cannot recall ever paying so much attention to an exhibition’s means of display. The frames selected for photographs by museums are usually minimal, modern and consistent in style, as befits a technical medium. In ‘The Radical Eye’, the pictures appear in the frames they occupy in John’s residence. They are as extravagant as the singer’s stage clothes, with gilded finishes and elaborately cut mouldings, and the effect is one of unbridled opulence. As many as four card or cloth-bound mounts of varying thicknesses encradle the pictures. Sometimes the unlikely frame choices work well; sometimes they overpower or merely over-egg the images, as in the frame for Herbert List’s Lake Lucerne, Switzerland (1936), showing two pairs of glasses by the water, which is adorned with circular motifs like spectacle lenses. One is constantly reminded of each picture’s domestic function as a decorative object – ‘precious gems’ John calls them – and his taste is inescapable.

While ‘The Radical Eye’ is unavoidably – if not by intention – an exhibition about the superstar celebrity as contemporary patron, it succeeds nonetheless as a thematic exposition of image-making in the Modernist era (up to around 1950). John’s interest in portraits of notable people – Picasso by Man Ray, Georgia O’Keeffe by Alfred Stieglitz, Igor Stravinsky by Edward Weston – is perhaps not so surprising. Toned and athletic bodies, leaping, diving and posing, form another favoured theme. One of the best is a curious František Drtikol picture from 1925 in which a female nude, perhaps a dancer, interacts enigmatically with a diagonal ‘wave construction’. Light carves the picture into starkly differentiated zones, a stage set for some obscure avant-garde celebration of the cult of the physique.

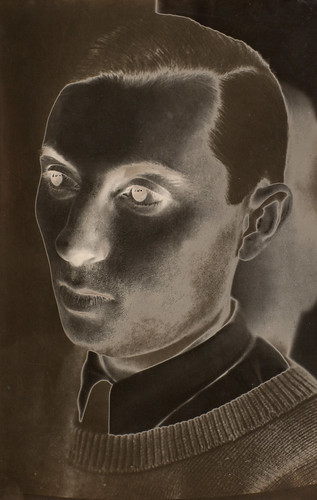

Maurice Tabard (1897-1984), Solarised man, 1930.

It is in the more experimental photographs that the show most intrigues, whether these acquisitions came from John’s evolving knowledge of the medium, astute curatorial guidance, or both. The collection includes fine examples of distortion, solarisation, double exposures, collage and photomontage, as well as images that find the marvellous in unexpected places. A wall devoted to masks has a bizarre picture from ca. 1935 by the German photographer Josef Breitenbach of a Parisian fireman whose head is entirely encased in a protective helmet, like a tribal face covering crossed with a space suit. In the words of Salvador Dalí, quoted nearby, ‘Nothing has proved the rightness of Surrealism more than photography.’

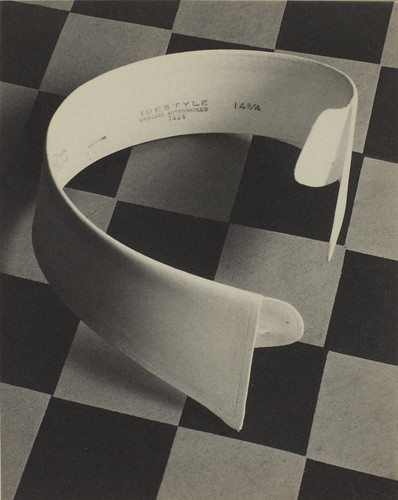

Paul Outerbridge (1896-1958), Ide Collar, 1922.

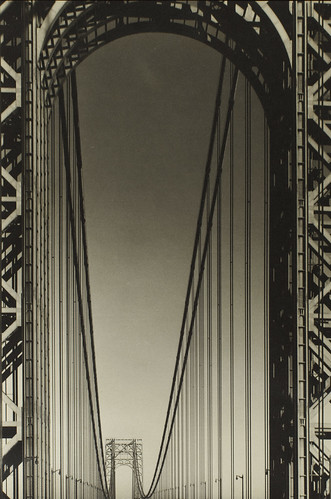

The final room features a centrepiece devoted to objects and here, in close-ups of a shirt collar (Paul Outerbridge), eggs in a wire basket (Imogen Cunningham) and typewriter keys (Ralph Steiner), the ‘new vision’ is seen in its purest form. The camera eye discovers properties in ordinary things that the everyday eye is apt to overlook. Unfamiliar perspectives – the inside of a radio transmission tower; an aerial view of two figures sitting on a bench – reveal the world anew. In Rail Spider, a stunning shot by Toni Schneiders, taken at the Hamburg-Altona railway terminus in 1950, a solitary worker is surrounded by the web of tracks radiating from a turntable used for moving locomotives between lines. In an interview in the catalogue, John confesses the awe he felt on finding such pictures exist. He wants others to feel the same. For better or worse, the show mixes pop celebrity and art history in a way that is starting to feel almost normal in our museums.

Margaret Bourke-White (1904-71), George Washington Bridge, 1933. © Estate of Margaret Bourke-White/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

Rick Poynor, writer, founder of Eye, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.