Spring 2023

Resistance is essential

Telegraf’s second issue embodies Ukraine’s creativity and courage in the face of the Russian invasion. Report by John L. Walters

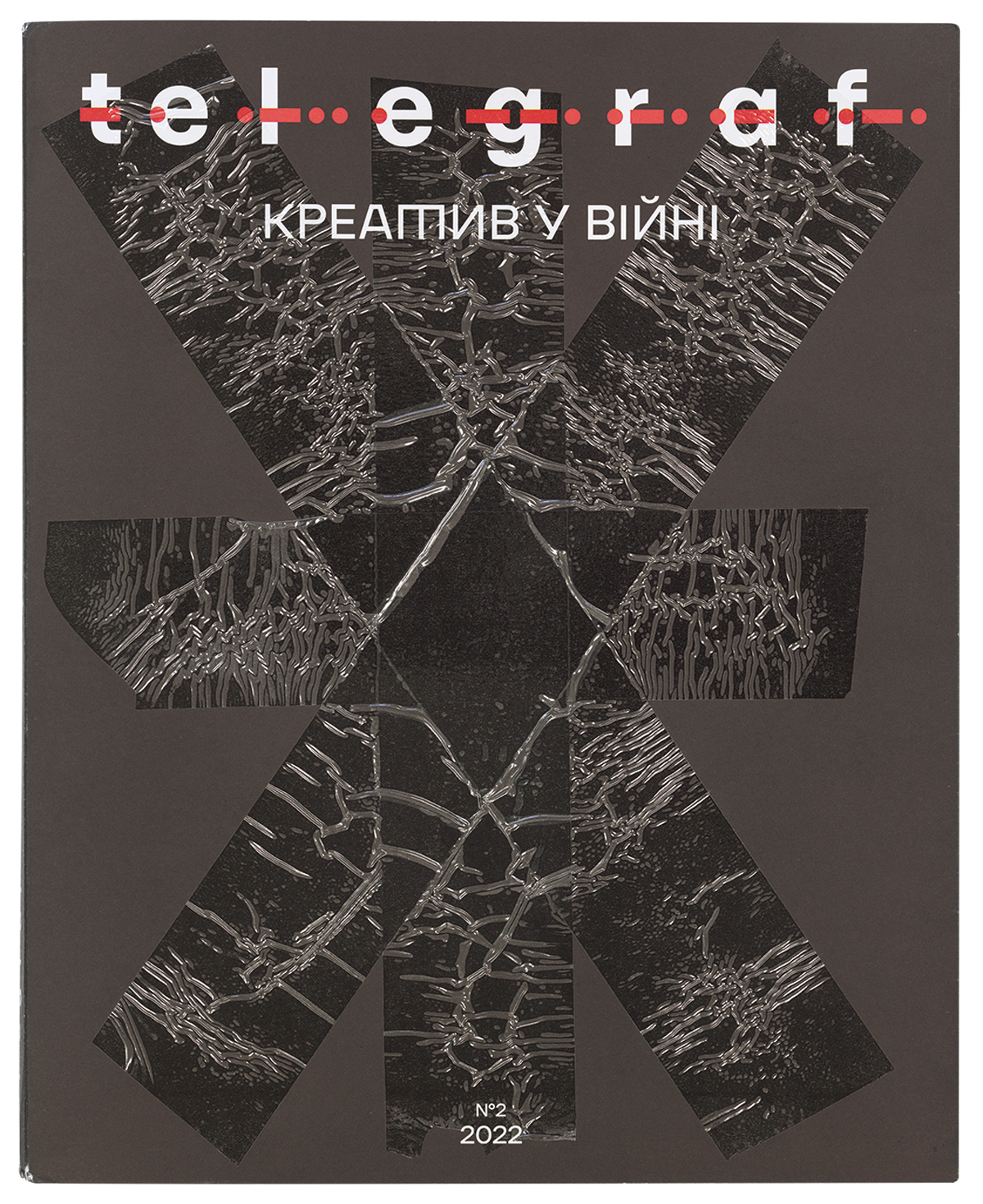

Each front cover of Telegraf no. 2 was taped by hand; a visual nod to duct-taping windows to protect them from shattering. Editor Anna Karnauh says: ‘Our art director Glib Kaporikov organised a master class for the women at the print house who did it. They were familiar with the concept of duct-taping window glass, but not paper.’

Telegraf is a Ukrainian magazine about design. Its first issue, in 2021, presented an enthusiastic overview of the country’s creative scene, a confident 200-page edition on good paper, the kind of independent magazine you might encounter anywhere in the world – a labour of love, yet highly professional.

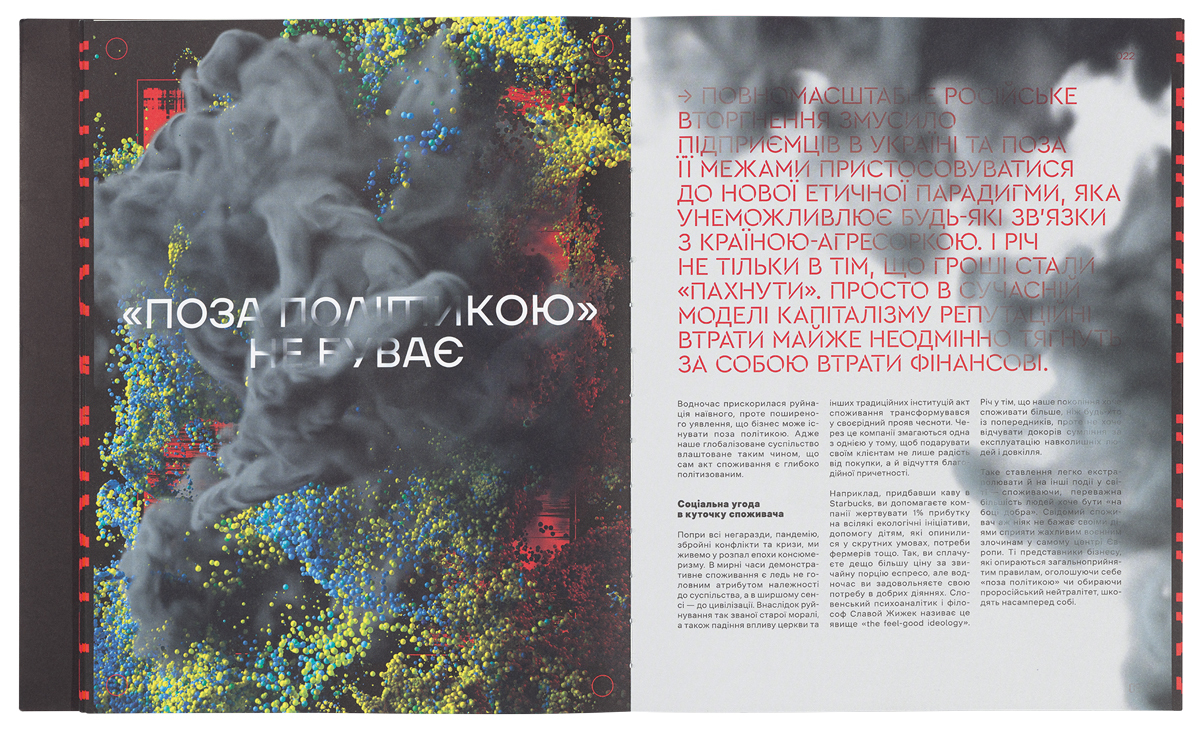

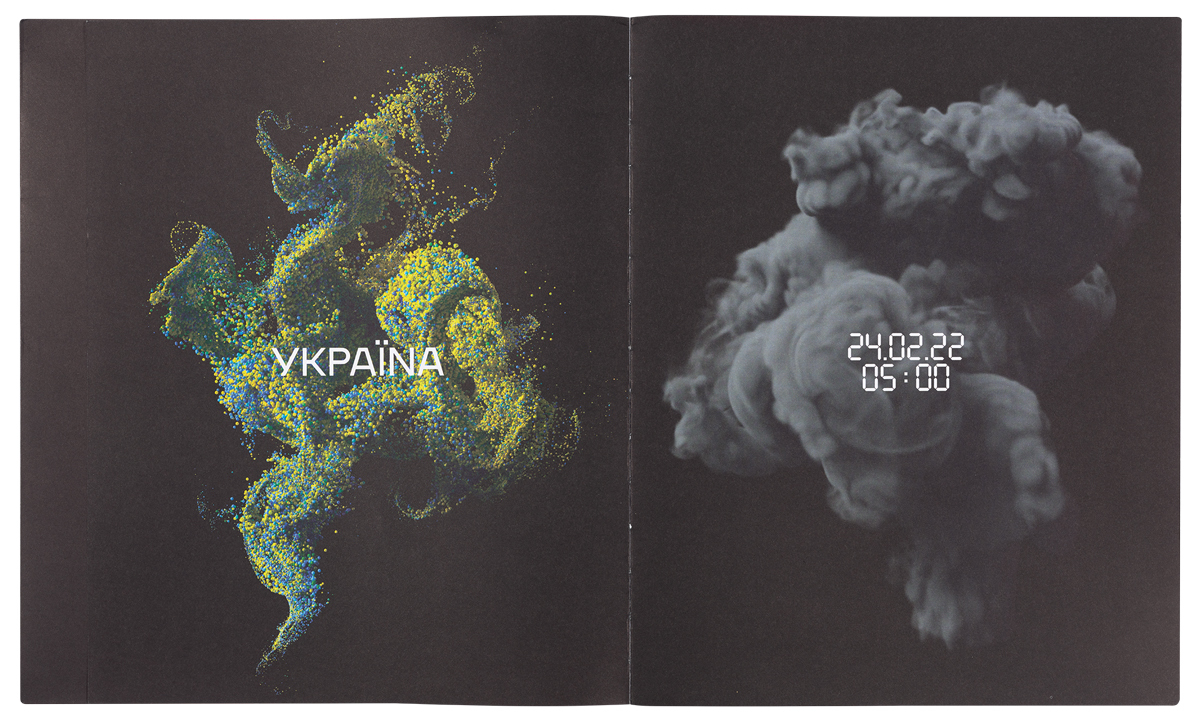

The second edition deals with the visual expression of a nation at war, an angry, heavyweight journal that almost ignites in your hands as you leaf through its contents. Swiss-bound and litho printed, the pages display a double fore-edge that states ‘Glory to Ukraine’ and ‘Glory to Heroes’. Instead of conventional folios, the page numbers are indicated by timings, starting at 5:00, the moment Russian armed forces attacked Ukraine on the morning of 24 February 2022. Each page is a minute, so that the article ‘Visual images of war’ begins on page 05:22. The concluding photo essay, twelve spreads that show plainly the devastation wrought by the invading Russian army, starts at 7:50. A linking theme in Glib Kaporikov’s confident art direction is the presence of thick smoke, as if from a recent blast, which swirls across the spreads, half-obscuring type and imagery. Emerging from this fog of war is an opposing cluster of digitally created spheres in Ukrainian blue and yellow, a motion-graphic, high-tech cypher for the country’s creativity and fighting spirit.

Spreads from Telegraf no. 2. The design of the magazine is an attempt to capture the experience of war through the eyes of civilians. At times, the smoke obscures the writing and affects legibility, acting as a ‘metaphorical veil’.

The issue is filled with recurring symbolic leitmotifs. Here, the spread visually juxtaposes the collaborative spirit of Ukrainian creativity (left) with the destruction of war (right).

The contents are structured in four sections: ‘The sight of war’; ‘It is personal’; ‘Fight for your light’; and ‘Legacy’. Editor Anna Karnauh writes: ‘Telegraf is about a new reality where creativity is the weapon against the aggressor, and every graphic work is not only a symbol, but also an instrument of resistance. Our magazine is about the courage to live in the midst of death.’

Lena Kovalchuk’s ‘Visual images of war’ article opens by discussing the roles of designers and illustrators on the ‘info-front’, in the first major war in the age of social networks: ‘Creatives create – they help to make a powerful informational resistance and deliver important messages about the war.’ When Ukrainian border guards responded to the enemy cruiser Moskva with the now legendary words, ‘Russian warship, go fuck yourself’, the phrase became the first symbol of the war. Designers and artists soon gave it a visual dimension. The Ukrainian postal service issued a stamp about the incident designed by artist Boris Groh; it was so popular that its online sales platform went down for several hours. Other visual symbols emerged. One was ‘The Ghost of Kyiv’, based on the urban legend of a MiG-29 Fulcrum flying ace credited with shooting down six enemy fighter jets in an hour on the first day of the Kyiv offensive. Another was AN-225 Myria – a plane destroyed at Hostomel airfield, ‘which in the imagination of illustrators,’ writes Kovalchuk, ‘became a guardian spirit that protects Ukraine from the sky.’

As for the country’s trident symbol [tryzub], the perception of it quickly changed from being one of official state bureaucracy to ‘a truly national one,’ Kovalchuk states, ‘emphasising the struggle and indomitability of our country’. Also in the issue, Jenya Polosina (whose Instagram @polosunya is a must-follow) provides a powerful rebuke to social media censorship with a handwritten, text-only panel. Illustrator Oleg Hryschenko notes that illustrators whose work was previously within children’s literature soon used their well practiced styles to express the tragedy of war.

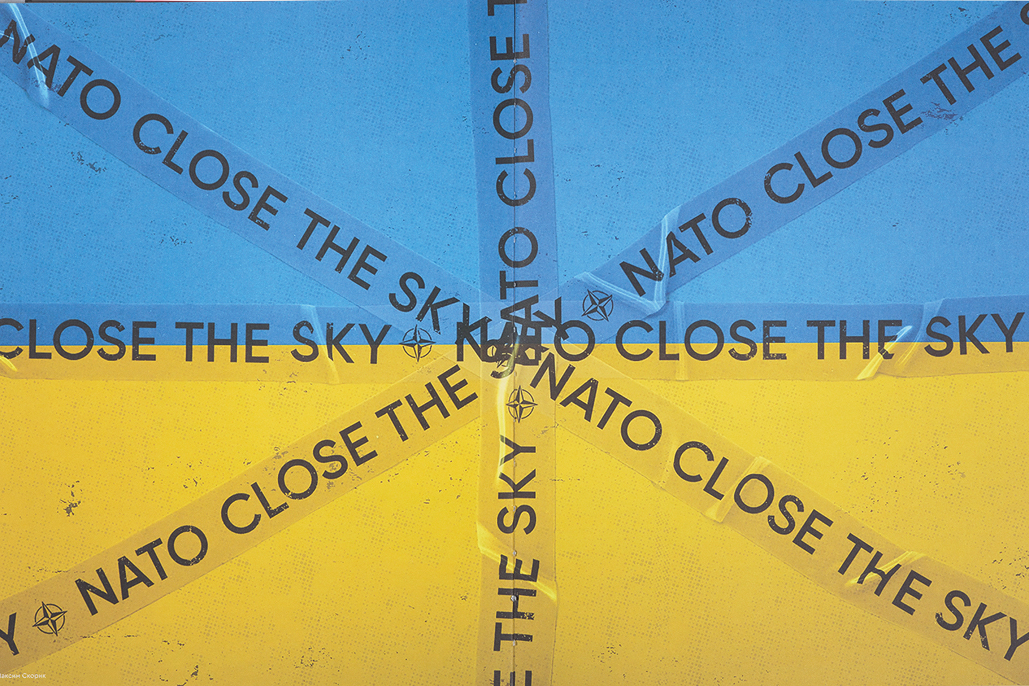

Nato Close The Sky, 2022, a poster by Kyiv graphic designer Maksym Skoryk.

Another dominant graphic device seen in Telegraf no. 2 is the criss-crossing window tape used to mitigate the effects of bomb blasts: witness Maksym Skoryk’s Nato Close The Sky, Evgeny Velichev’s All Windows in Ukraine and the magazine’s bleak, unforgettable front cover.

The issue also features practical guides to making protest posters; and a first-person report from Svyatoslav Kholod, a games designer at Snapchat who volunteered to become a gun commander. He says that ‘in the army, peacetime design skills, in particular communication and teamwork, become an adventure. Conflicts arise, but are quickly resolved. Our interaction resembles work in an agency or design team: we have a common cause … team management works everywhere.’

In the ‘legacy section’ there is an article about the history of Ukrainian posters by Oleksandra Korchevska-Tsekhosh, with a focus on artists such as Leo Kaplan, Vasyl Yermilov and Adolf Strakhov. The article brings us to the present day via the country’s independence in 1991, the Maidan revolution of February 2014 and last year’s invasion. ‘Ukrainian posters are now a community of dogs of war,’ writes Korchevska-Tsekhosh, ‘who sink their teeth into hostile contexts and rightly tear the skin and sinews of disinformation exposing the muscles of truth.’

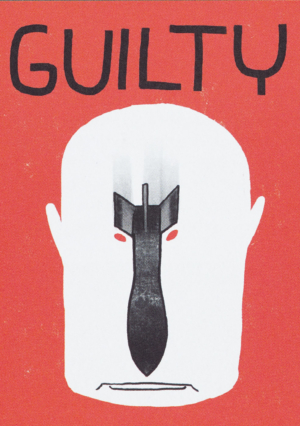

Guilty poster by Oleksandr Shatokhin, an illustrator living in Sumy.

The Ghost of Kyiv poster by Lviv-based artist Mykhailo Skop.

Editor Anna Karnauh spoke to Eye about the origins of Telegraf.

Anna Karnauh ‘Our first edition was partly dedicated to underlining our difference from the world and from Russia, because our story is that of a country into which Big Brother Russia has

attempted to expand. And in those conditions, we developed something unique. We are trying to open eyes for designers and Ukrainians, to show we have something to be proud of … our own identity. But we are part of the global process because of the globalisation that’s here in Ukraine. A lot of Ukrainian designers are involved in international tech products made by Facebook or Google. We had an interview with one of the first designers of WhatsApp, who designed its first icon.’

Eye Why make a print magazine?

‘Our publisher Sasha Tregub, Glib [Kaporikov] and I had the idea to make a print magazine as a tribute to the Ukrainian design and creative community – and for fun. We didn’t plan to do it on a regular basis. Then the pandemic broke out, which made things harder, but we managed to finish our first issue; we made it the best we could. And printed magazines are now. Everyone, especially in Ukraine, lives with their phones in their hands, just scrolling the bad news. Information enters you … you don’t have time to stop. But when you have a magazine, it’s not as monumental as a book. It’s in between. You are still in the process, but you can step back and look from outside. It is nice to have something in your hands that you can flip through and read.’

How did the launch go?

‘We presented the issue on Friday 30 September 2022 in Kyiv. Most of the people we had invited to participate in the discussion were illustrators and designers featured in Telegraf, including Jenya Polosina, Dmytro Bulanov and art director Glib Kaporikov. It was really nice. People have missed such gatherings, in an art gallery with a glass of wine. It was like the good old times, before 24 February. The air raid alert started just after we finished our event. So we got lucky, I guess.’

John L. Walters, editor of Eye, London

First published in Eye no. 104 vol. 26, 2023

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.