Sunday, 6:00pm

26 July 2020

The haunted shore

Images of spectral sea-bathers haunt the light-filled pages of Nigel Grierson’s self-published photobook.

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for Eye magazine.

As collectors and historians have definitively established in the past twenty years, the era of photography has also been the era of the photobook. The medium of the book, even more than the exhibition, gives photographers total control over how their work is presented, and the carefully edited photobook, usually devoted to a single theme, becomes a work in its own right. The past decade has seen an international explosion of photobooks, many of them made by photographers taking their cue from Publish Your Photography Book (2011). The mood of defiant self-definition was cheerfully summarised by another thriving initiative established to encourage photographic dissemination: Self-Publish, Be Happy.

Nigel Grierson’s new photobook publishing venture, Lost Press, is a collaboration with his brother Robin Grierson, also a photographer. Grierson, N. will be known to admirers of the independent record label 4AD’s early releases. In the 1980s, working under the enigmatic name 23 Envelope, he and his partner, the late Vaughan Oliver, created era-defining record sleeves suffused with an atmosphere of otherworldliness and mystery. At the time they were reluctant to separate their creative contributions, but the sumptuous photographs were Grierson’s (see Eye 37). After they split up, Grierson made music videos and TV commercials before eventually returning to photography. In 2014, Dewi Lewis published Photographs, an engaging survey of his work in a range of styles, which did not quite cohere into the unidirectional requirements of a photobook.

Cover of Nigel Grierson’s Lightstream, published by Lost Press, 2020.

Top. Untitled.

Grierson’s first degree was in graphic design and he chose to design Photographs himself. His two new books, Passing Through and Lightstream, both self-funded, are recognisably the work of the same hand: standard hardback bindings, dust jackets with immersive details from Grierson’s pictures, and flaps, where some information could go, left stark white. The pages are similarly minimal and the untitled, undated pictures are mostly left to speak for themselves, though Lightstream, which I want to focus on here, is bookended by epigraphs from the artist Dieter Appelt (‘A snapshot steals life that it cannot return. A long exposure (creates) a form that never existed.’) and a Leonard Cohen poem (‘Listen to the hummingbird / Whose wings you cannot see / Listen to the hummingbird / Don’t listen to me’).

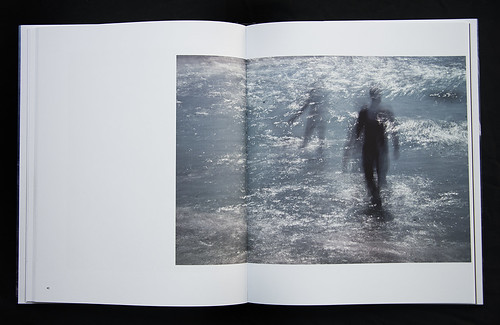

The 36 photographs in Lightstream were all shot on the beaches of Brighton and Whitstable. They have their origins in a few earlier experiments and the project took shape from 2012 to 2018. The pictures document people by the water or bathing in the sea, but the original figures of ordinary holidaymakers have morphed into spirits and phantoms, all the colour and pattern drained from their beachwear, their faces melting into shadow. A few retain a degree of corporeal solidity, while others are no more than smudges and blurs against the seascape. The sea is transformed into a flickering field of illumination, as though the waves have become vaporous and ethereal, and it is often hard to tell the difference between liquid and air. People wallow in the currents of the ‘lightstream’ or remain motionless in silent contemplation. A solitary dark wader, his profile sharp in silhouette as his boundaries dissolve, gazes down at the ineffable surface. A group of partially submerged bathers appear to be approaching a moment of final assimilation into the flowing primal waters.

Spreads from Nigel Grierson’s Lightstream, 2020.

Grierson’s images have the visual texture and grandeur of paintings. Yet the technique is conventionally photographic. He makes the digital pictures with unusually long exposure times and each outcome is a record of what the camera observed. The fluctuations of light produce the abstraction – some images have erratic lines and marks like spontaneous drawing – and chance plays a significant role in their formation. The only manipulation of the picture is occasional cropping and what Grierson describes as normal levels of tonal grading.

As with any photobook, editing plays a crucial role. Which pictures will be selected or rejected? Grierson calls this the ‘decisive moment’. He was looking for images ‘where the movement and marks appear to add up to something more than the sum of their parts’. Once an image is chosen, the challenge is to determine its most effective place within the picture sequence. Grierson favours a single photo per spread, always placed on the right-hand page and generally with a white border. There are only two full page bleeds and one occasion where a landscape image is permitted to straddle the gutter. The sequence flows smoothly – the more I studied it, the more I felt he had arrived at the right tension and pace. The book evolves towards a series of light ‘drawings’ where squiggles of luminescence efface the beach people until, by the end, only the dancing brightness remains.

Nigel Grierson, Untitled.

Lightstream feels entirely consistent with the concerns of Grierson’s earliest photographs, while marking a significant development. The pictures uncover another world inside this one, to paraphrase an old Surrealist saying, a realm both ravishing and mournful. I imagine many of these images would have great impact as large, standalone prints, but the photobook’s more complex construction enables an intensification of effect. Each picture becomes another facet in the haunting alternative reality inscribed on the camera’s sensor.

Nigel Grierson, Untitled.

Lightstream and Passing Through will be available in September and can be pre-ordered at Lost Press (link below) and online bookshops.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.